Sorting through some papers the other day, I found the final regular column Susie Boyt wrote for the Financial Times, in which as a farewell gesture she endeavoured to provide a list of life-truths, if that is the right word, (or right hyphenated term).

I remember that I kept a copy of the column because I felt sad that she was quitting. As it happens, I think that she has come back, writing the column on an occasional basis, but at the time it seemed we were seeing the last of her whimsical imagination, and I felt sad. My sadness led me to go out and buy a novel she had written - with the idea of filling the gap left by the missing column - and, as a result, I discovered, disappointingly, that Boyt's talent is bettered suited to being a columnist than a novelist. Never mind. Although my respect for her was slightly diminished by that experience, Boyt still seems to me to be a spirit that one wants to be fond of rather than not.

Certainly, in the set of life truths she supplied in that, as it turned out, not quite final FT column, there are many things that I agree with and others that at least provoke a bit of thought.

Here is the list, without any comment from me on which are, to my mind the most endearing or the most intriguing points she makes:

Things that are hard have more of life at their heart than things that are easy.

The future must prove better and happier than the past.

All feelings, however painful, are to be prized.

Glamour is a moral stance.

Loss, its memory and its anticipation, lies at the heart of the human experience.

If you have a thin skin all aspects of life cost more and have more value.

The world is crueller and more wonderful than anyone ever says.

You must try to prepare and be ready for the moment that you're needed, for the call could come at any time.

There are worse things in life than being taken for a ride.

Grief is no real match for the human heart, which is an infinitely resourceful organ (she adds - I really hope that one is true)

I am grateful to Susie Boyt for this list and for the pleasure her columns have given me

Tuesday, 28 May 2019

Monday, 27 May 2019

A Mirror Written Cake

Yesterday we went over the river and up the hill to Budapest's Castle District to look at an exhibition of photographs we'd seen a poster for. The exhibition displays part of a project called Fortepan.

Fortepan is a vast archive of photographs that started as a collection made by Miklos Tamasi and Akos Szepessy, two friends, who from the 1990s onwards bought discarded pictures in jumble sales and gathered them up from the street throw-outs that happen in each Budapest district twice a year. When they put what they had online in 2010, other people joined in, adding their own photographs. The archive is enormous and fascinating and you can find it here.

The exhibition from the archive is beautifully curated so, if you are in Budapest, I recommend going to see it - it is on until 25 August. Even though all the photographs on display can be found on-line, the way they are presented in the exhibition adds resonance and depth to the experience of looking at them. Having forked out an absurdly large sum of money recently to see the exhibition of Martin Parr's pictures at London's National Portrait Gallery, I was struck by how this haunting collection of amateur snaps manages to ask many of the questions he asks with his photography and to highlight many of his themes, but without what I felt was his slight arrogance and mild contempt for humanity. Because of the mixed fortunes of the Hungarian nation during the last century or so, the pictures also tell a very remarkable and poignant story, showing hardship and resilience and a lot of sadness.

There were two particularly striking sections of the exhibition that it would be especially hard to replicate by looking through the digital archive. I will therefore try to give an idea of them here.

The first was a set of displays called something like Twin Pictures (that wasn't exactly its name, but I can't recall the precise title). In this section, you saw a photograph that appeared to be hanging by itself on the wall, but you then realised there was a small handle in the middle of the bottom of the photograph's frame. When you lifted this, you discovered the photograph you'd been looking at was actually mounted on a hinged board. When you raised the board, another photograph of the same subject but taken at a different moment was revealed hanging underneath.

Some of the twinned pictures were dreadful, highlighting the effects of war and revolution:

This one, for instance, shows the Castle District seen from a balcony, probably on the lower slopes of the Gellert Hill, in 1943.

This one shows the same scene from the same vantage point in 1946. Incidentally, both are from the collection of Carl Lutz, who was Swiss vice consul to Hungary during the Second World War and saved tens of thousands of people's lives, an extraordinary and very courageous man, who thought nothing of plunging into the icy Danube to rescue someone the Arrow Cross were trying to murder and then - still drenched, in freezing weather and soaked clothes - taking on the German authorities who were allowing the attempted murder to take place. You don't meet many like him on the ordinary diplomatic circuit

This picture shows Kossuth Lajos street in 1954, during a May Day parade:

This shows the same scene during the 1956 uprising. Both can be found in much more vivid detail at the Fortepan site. Search for the first by entering the number 129449; for the second, enter 129465.

In response to this picture, another person wrote: "The smiling face of our father, who died 25 years ago, can be seen in some of the pictures. He is one of the goalkeepers and can be seen squatting in the middle of this shot. The picture must have been taken in the late 1960s or early 1970s at the playing field belonging to the Motorcycle and Machine Factory on Fehervari Street. I was born in 1970 and I have a clear but fleeting memory of my father waving at me from behind the fence."

This one similarly brought back a lost relative for someone: "I discovered my grandmother in a 1959 photograph on your website. Sadly, she passed away in 2010, and I was over the moon to see her again in this way. I've been living abroad for a long time and so this is a true delight for me."

This, meanwhile, brought back a memory of a schoolfriend: "The picture of schoolchildren on bicycles was made around 1960 in Ujpest. A group of schoolchildren were taking part in a road traffic course. Perhaps this explains the new bicycles. I discovered in the middle of the picture Otto Lecz, a dear classmate of mine from high school. Sadly he passed away some years ago. We both attended the prestigious Konyves Kalman High School between 1960 and 1964. To the archive's creators, best wishes for 2018 from Mexico, where I have been living for 45 years."

I have always wondered why we take photographs, what the point is of trying to capture moments that we are not experiencing because we are taking photographs to try to capture them. However, confronted with these photographs, en masse, I have begun to wonder about my reservations. Looking at the pictures in this enormous collection, time and human life take on a slightly different aspect. Although the individual photographs often seem insignificant, (except, as is obvious from the letters above, to those for whom they have a special meaning), seen as a group they acquire a mysterious resonance. In some strange way, they seem to be collectively expressing something about time. What exactly that something is, I'm not sure; what I am certain of though is that the Fortepan site is one of the best ways I've found in years of consuming hours and hours.

Fortepan is a vast archive of photographs that started as a collection made by Miklos Tamasi and Akos Szepessy, two friends, who from the 1990s onwards bought discarded pictures in jumble sales and gathered them up from the street throw-outs that happen in each Budapest district twice a year. When they put what they had online in 2010, other people joined in, adding their own photographs. The archive is enormous and fascinating and you can find it here.

The exhibition from the archive is beautifully curated so, if you are in Budapest, I recommend going to see it - it is on until 25 August. Even though all the photographs on display can be found on-line, the way they are presented in the exhibition adds resonance and depth to the experience of looking at them. Having forked out an absurdly large sum of money recently to see the exhibition of Martin Parr's pictures at London's National Portrait Gallery, I was struck by how this haunting collection of amateur snaps manages to ask many of the questions he asks with his photography and to highlight many of his themes, but without what I felt was his slight arrogance and mild contempt for humanity. Because of the mixed fortunes of the Hungarian nation during the last century or so, the pictures also tell a very remarkable and poignant story, showing hardship and resilience and a lot of sadness.

There were two particularly striking sections of the exhibition that it would be especially hard to replicate by looking through the digital archive. I will therefore try to give an idea of them here.

The first was a set of displays called something like Twin Pictures (that wasn't exactly its name, but I can't recall the precise title). In this section, you saw a photograph that appeared to be hanging by itself on the wall, but you then realised there was a small handle in the middle of the bottom of the photograph's frame. When you lifted this, you discovered the photograph you'd been looking at was actually mounted on a hinged board. When you raised the board, another photograph of the same subject but taken at a different moment was revealed hanging underneath.

Some of the twinned pictures were dreadful, highlighting the effects of war and revolution:

This one, for instance, shows the Castle District seen from a balcony, probably on the lower slopes of the Gellert Hill, in 1943.

This one shows the same scene from the same vantage point in 1946. Incidentally, both are from the collection of Carl Lutz, who was Swiss vice consul to Hungary during the Second World War and saved tens of thousands of people's lives, an extraordinary and very courageous man, who thought nothing of plunging into the icy Danube to rescue someone the Arrow Cross were trying to murder and then - still drenched, in freezing weather and soaked clothes - taking on the German authorities who were allowing the attempted murder to take place. You don't meet many like him on the ordinary diplomatic circuit

This picture shows Kossuth Lajos street in 1954, during a May Day parade:

This shows the same scene during the 1956 uprising. Both can be found in much more vivid detail at the Fortepan site. Search for the first by entering the number 129449; for the second, enter 129465.

More cheerful was this pair, in the background of which you can see the building where the Fortepan exhibition is being held:

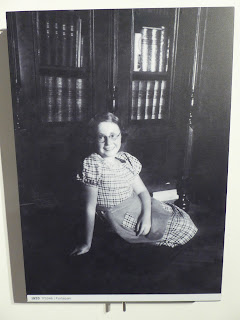

In this sequence, I though there was something very touching about the character of the person in both photographs: in the second we see she has grown up but has not lost a certain innocent openness in the process:

The other section that I thought had been brilliantly conceived by the curators was one in which they chose to display the letters they had received from members of the public who had come upon a picture they recognised in the archive. The letters are very touching; their writers are so thrilled to have a little glimpse back into their past and to see people they were fond of who are no longer around.

In response to this next picture, someone wrote to the archive: "Fortepan is a wonderful thing. I suddenly came across the old family shop with our old family home. It was my great-grandmother Mrs Izso Gotzler (Debora Neumann) who founded the corsetry shop in Ujpest. After the war her daughter took over the business, because Debora never returned from Auschwitz. By the time I was born, the shop had closed and Manyoka (Margit) had gone into retirement: there were few memories of the house. Then I happened to open the Fortepan site and there was the shop wth Manyoka on the signboard."

Imagine having to write about a relative, "Debora never returned from Auschwitz".

In response to this picture, another person wrote: "The smiling face of our father, who died 25 years ago, can be seen in some of the pictures. He is one of the goalkeepers and can be seen squatting in the middle of this shot. The picture must have been taken in the late 1960s or early 1970s at the playing field belonging to the Motorcycle and Machine Factory on Fehervari Street. I was born in 1970 and I have a clear but fleeting memory of my father waving at me from behind the fence."

(I should explain that the title of this post refers to my mind's insistence on thinking of Fortepan as Panforte, which is, of course, a Sienese cake)

Sunday, 26 May 2019

Night Thoughts

The things I've been fretting about when I wake at three in the morning:

Death, of course, that goes without saying

Pride - can it be true that there have been marches in favour of pride going on for years, and I've never noticed? Why the abbreviation from Gay Pride? Can celebrating pride, pure and simple, without adjectival distinction, ever be anything but, at least smug and at worst callous?

Whether a society in which a young man can grow up thinking it is reasonable to try to punish someone he believes has sold him the wrong goods by throwing sulphuric acid at him is redeemable - especially when that young man, having allowed that acid to burn someone totally unconnected with him, does nothing and, when that same person dies and he is sentenced for her manslaughter, his reaction contains no discernible trace of empathy

Why interesting films it might be worth leaving the house to watch now seem so rare.

Whether, on narrow pavements, those of us who walk very fast should feel that those who walk slowly should hurry up, or whether we should instead be grateful for the opportunity to slow down (I do remember a relative asking me, "Why do you walk so unnecessarily fast?")

Whether dust is really god's way of protecting the furniture or whether perhaps I am just deluding myself.

Whether peonies - bought as tight buds at the local market but over the last few days opening bit by bit - are the prettiest flowers of all:

Death, of course, that goes without saying

Pride - can it be true that there have been marches in favour of pride going on for years, and I've never noticed? Why the abbreviation from Gay Pride? Can celebrating pride, pure and simple, without adjectival distinction, ever be anything but, at least smug and at worst callous?

Whether a society in which a young man can grow up thinking it is reasonable to try to punish someone he believes has sold him the wrong goods by throwing sulphuric acid at him is redeemable - especially when that young man, having allowed that acid to burn someone totally unconnected with him, does nothing and, when that same person dies and he is sentenced for her manslaughter, his reaction contains no discernible trace of empathy

Why interesting films it might be worth leaving the house to watch now seem so rare.

Whether, on narrow pavements, those of us who walk very fast should feel that those who walk slowly should hurry up, or whether we should instead be grateful for the opportunity to slow down (I do remember a relative asking me, "Why do you walk so unnecessarily fast?")

Whether dust is really god's way of protecting the furniture or whether perhaps I am just deluding myself.

Whether peonies - bought as tight buds at the local market but over the last few days opening bit by bit - are the prettiest flowers of all:

Sunday, 19 May 2019

The Limitations of Logic

We live in a flat that can only be reached by climbing ninety-six stairs. This means that it is difficult for many of our friends to visit us - they are too old to manage the climb, or, due to accident or illness, too weak in lung or limb.

I have a very good logical solution to this, which would mean they could visit easily. My solution is to employ some strong young men - they could be attractive too, if this would be helpful - to carry frail guests up the staircase. There is no shortage of hail and hearty males available - they happily run up and down the stairs with new fridges and bits of furniture when we buy them. The availability of the means of transport is not a problem at all.

But somehow, even though this is a rational, logical solution to a problem, it will not do. Illogical though it most definitely is, I know no one who is prepared to be carried anywhere, upstairs, downstairs or along flat ground. There is a loss of dignity involved that makes it better simply to refuse to attempt the ascent to flats on high floors if the only means of transport is a fireman's lift. I understand this although I cannot explain it in rational terms.

Similarly, the way I reacted the other day to what was, logically, a perfect question for starting a conversation, defied good sense. It was at a social gathering to which I'd been invited as my husband's wife - that is to say, it was his achievements that had resulted in our attendance, not my own, meagre as they are.

At this event, a very high-powered woman involved in Washington politics found herself stuck next to me and decided to try to make conversation. After exchanging names and our reasons for being at the party, she sallied forth boldly with the question, "What are your interests?"

Again, just as logic dictates that hiring men to carry my more infirm guests upstairs makes sense, the clever woman's question was, logically, excellent. If you want to get to know someone, it's obvious - ask them about themselves, ask them for the information you need. It's a straightforward approach. It seems so reasonable - the data is lacking, so ask for it.

Yet it isn't, because, once again, it turns out that human beings are not always straightforward - at least I'm not. The very idea of being put on the spot and asked, bluntly, to talk about myself, appalled me. Leaving aside the fact that I was told repeatedly throughout my childhood never to be pushy, on what basis would I reveal myself to a stranger? When you meet people, in my reality at least, you need to meander about conversationally, talking about neutral things, until you have established that your perspectives are vaguely similar and you can more or less trust each other enough to discuss the important things in life. Until I'm sure of the temperament of an interlocutor, my aim is to deflect personal questions - and not only out of an instinct for self-preservation, but also from a desire not to come across as a self-obsessed bore.

Mind you, in my case my interests are so abnormal that my reaction is actually probably not really all that illogical anyway, when you come down to it. I realised this when, too shocked to think of an alternative strategy, I endeavoured to answer the Washington woman honestly. I heard myself saying, "Handspinning alpaca wool, making patchworks out of my husband's old shirts, listening to The Archers", and I saw her eyes glaze with boredom (or was it horror?) at almost the speed of light. And I hadn't even got on to the comparative grammar systems of Slavic, Romance and Finno-Ugric languages or the merits of Gregg shorthand in comparison to Pitman's, the mysterious quality of the paintings of the Northern Primitives and the difficulty of choosing between van Eyk and van der Weyden, the wonders of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and ...

Conversation, I realised at that moment, needs to proceed irrationally, each participant a diver in deep, dark water, groping for handholds in the uncertain gloom. Hurling a sensible question into the mix has the effect of a harpoon plunging into a rockpool, sending everyone scuttling back into their respective crevices and holes.

I have a very good logical solution to this, which would mean they could visit easily. My solution is to employ some strong young men - they could be attractive too, if this would be helpful - to carry frail guests up the staircase. There is no shortage of hail and hearty males available - they happily run up and down the stairs with new fridges and bits of furniture when we buy them. The availability of the means of transport is not a problem at all.

But somehow, even though this is a rational, logical solution to a problem, it will not do. Illogical though it most definitely is, I know no one who is prepared to be carried anywhere, upstairs, downstairs or along flat ground. There is a loss of dignity involved that makes it better simply to refuse to attempt the ascent to flats on high floors if the only means of transport is a fireman's lift. I understand this although I cannot explain it in rational terms.

Similarly, the way I reacted the other day to what was, logically, a perfect question for starting a conversation, defied good sense. It was at a social gathering to which I'd been invited as my husband's wife - that is to say, it was his achievements that had resulted in our attendance, not my own, meagre as they are.

At this event, a very high-powered woman involved in Washington politics found herself stuck next to me and decided to try to make conversation. After exchanging names and our reasons for being at the party, she sallied forth boldly with the question, "What are your interests?"

Again, just as logic dictates that hiring men to carry my more infirm guests upstairs makes sense, the clever woman's question was, logically, excellent. If you want to get to know someone, it's obvious - ask them about themselves, ask them for the information you need. It's a straightforward approach. It seems so reasonable - the data is lacking, so ask for it.

Yet it isn't, because, once again, it turns out that human beings are not always straightforward - at least I'm not. The very idea of being put on the spot and asked, bluntly, to talk about myself, appalled me. Leaving aside the fact that I was told repeatedly throughout my childhood never to be pushy, on what basis would I reveal myself to a stranger? When you meet people, in my reality at least, you need to meander about conversationally, talking about neutral things, until you have established that your perspectives are vaguely similar and you can more or less trust each other enough to discuss the important things in life. Until I'm sure of the temperament of an interlocutor, my aim is to deflect personal questions - and not only out of an instinct for self-preservation, but also from a desire not to come across as a self-obsessed bore.

Mind you, in my case my interests are so abnormal that my reaction is actually probably not really all that illogical anyway, when you come down to it. I realised this when, too shocked to think of an alternative strategy, I endeavoured to answer the Washington woman honestly. I heard myself saying, "Handspinning alpaca wool, making patchworks out of my husband's old shirts, listening to The Archers", and I saw her eyes glaze with boredom (or was it horror?) at almost the speed of light. And I hadn't even got on to the comparative grammar systems of Slavic, Romance and Finno-Ugric languages or the merits of Gregg shorthand in comparison to Pitman's, the mysterious quality of the paintings of the Northern Primitives and the difficulty of choosing between van Eyk and van der Weyden, the wonders of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and ...

Conversation, I realised at that moment, needs to proceed irrationally, each participant a diver in deep, dark water, groping for handholds in the uncertain gloom. Hurling a sensible question into the mix has the effect of a harpoon plunging into a rockpool, sending everyone scuttling back into their respective crevices and holes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)