Someone I know - let's say her name is Elsa, (it isn't) - lives in the south west of England, (actually, she lives in a different region) but comes originally from Australia (this bit and all the rest, except the place names and her friend's name, are true). Usually, Elsa goes home for a month or two in the European winter, to get a bit of sun into her bones.

But this year that's out of the question.

As a result, when Elsa's rather wild friend Xan, (a glamorous old thing who plans to go for a facelift in Turkey when this is all over), rings one gloomy morning and suggests they go for a sunbed, Elsa doesn't do what she and all Australians would normally do and shriek in horror at the idea of any unnecessary extra exposure to damaging UV rays, (even though that is how we have all been brought up to react to such suggestions since infancy). Because it is the middle of a British winter and Elsa feels a glimpse of sun, even sunbed sun, would actually be quite helpful, Elsa says she'd love to. Actually, she says she'd love to, but how exactly is it going to happen? It's lockdown, no sunbed places are open. To which Xan replies, Ah, but there is a sunbed place she's found out about, an illicit sunbed place, operating in Ottery St Mary.

This is what happens when you bring in a strict lockdown, Elsa thinks, a whole industry of illicit sunbed places springs up. Or at least one does. Even one is absurd.

How the hell did we arrive at a situation where people are running illicit sunbeds, Elsa asks Xan - in which crystal ball could this have been foreseen? Xan says she doesn't know but does Elsa want to come with her? Elsa cuts the philosophising and says she definitely does want to, and the two of them agree to go that afternoon.

By the time Xan picks up Elsa from her house, the rain is already beginning. As they head out of town, the sky ahead of them is zigzagged by tremendous bolts of lightning. Thunder follows and finally the heaviest downpour either of them have ever seen. Visibility is reduced to almost nothing. Xan, always a slightly alarming driver, becomes, at least in Elsa's eyes, downright terrifying, alternating spurts of anxious acceleration with sudden braking. She also appears to have forgotten that in the narrow old lanes that they are soon navigating you sometimes encounter another car coming the other way.

But in this weather maybe Xan has simply realised that there will not be anything else coming in any direction. Certainly, they don't see anyone at all during the rest of the journey, so it would be an accurate calculation to assume no one other than them would be mad enough to be out in a car.

And eventually, after a great deal of lurching and several extremely dramatic episodes of skidding, what Elsa claims must have been at least a hundred potholes (plus, according to her, numerous near collisions with hedgerows), they are at last getting close to their destination. Then, at the moment that the sign indicating the turn off to Ottery St Mary emerges from the murk beyond the windscreen, Xan's telephone springs into life. Elsa snatches it from Xan, who is about to answer it while negotiating the turn.

The caller has a broad West Country accent but the content of his conversation is pure Chicago mobster. The cops are hanging round out the front, they've been after him all week - Xan and Elsa will have to cruise around the back streets of Ottery St Mary for about half an hour. That should mean it will be properly dark when they arrive, (from Elsa's point of view it already is, although strictly speaking night hasn't fallen, but she doesn't quibble), and, if they come in the back way, with any luck the cops won't see them or will already have packed up and gone home.

Elsa notes down all the West Country mobster's instructions. The two women spend half an hour discovering the glories of Ottery St Mary, (what a splendid garden centre; good heavens, they have their own hospital - and an enormous Sainsbury's!). Then Elsa reads out the instructions to Xan, and after another three-quarters of an hour of getting lost and retracing their progress, they find the address of the prohibited sunbed place.

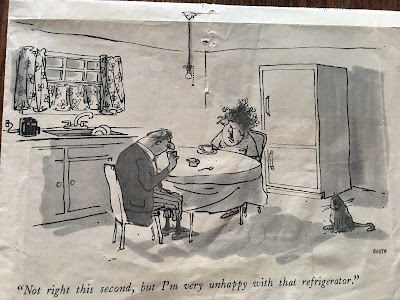

They scuttle out of the car and down a side alley. They ease themselves through a gap created by pushing two slats of someone's back fence aside. They make their way towards the back of a small house and go through a glass sliding door into somebody's kitchen. The room is, not to put too fine a point on it, a little malodorous, possibly thanks to the wellfed dog lying on a large pillow and snoring by the door.

In the middle of the room, there is a man sitting at a table, smoking a cigarette and watching a boxing match on a small laptop. He looks up as they come in. Sure enough, he is the man Elsa spoke to on the telephone - owner and operator of a range of illicit sunbeds, if two can be said to constitute 'a range'.

He takes the women through to what was probably originally designed to be a sitting room. He switches on the sunbeds and leaves them to it.

Elsa and Xan undress and lie down. Elsa is enough of an Australian to stay in the sunbed for only a very short period. After a six-minute blast, she climbs out, dresses and goes back to the kitchen. Xan tells her that she will stay under the lights for a few minutes more.

Back in the kitchen, the man is still watching boxing. Elsa asks if she can pour herself some water. The man nods and Elsa picks up a glass from the draining board. She turns on the tap. There is a crack of lightning, followed almost immediately by a crash of thunder. All the lights go out.

The man swears. He gets up and goes out to where the sunbeds are. Elsa follows him. Xan is lying on a sunbed with no sun in it, struggling to open the top of the thing and get herself out.

"It's no good", the man tells her. "It's a design fault - they lock themselves if the electricity ever goes off." Xan becomes angry, but the man insists there's nothing he can do about it. The lightning must have hit the local transmitter, he says - it happens sometimes, but she doesn't need to worry as they don't usually take too long to get the thing up and running again.

Xan has no choice. She has to accept the situation. Elsa and the man make their way back to the kitchen. Although the only source of light is the small amount the lap top sheds onto the table, the man snaps the thing shut, plunging the room into darkness. The dog groans in its sleep.

Presumably the man doesn't want to waste the laptop battery. All the same, Elsa regrets the disappearance of its glow. Outside it is pitch black - and now it is equally dark indoors.

The man, it turns out, is a bit of a talker. Sitting in the blackness, he starts to tell Elsa about his political theories. The virus is a conspiracy, he says, the lockdown is a conspiracy, the US election was rigged, nothing is what it seems.

The man talks and talks. Elsa makes little sounds of if not exactly agreement at least non-aggression. She begins to wonder whether she is sitting in the dark with someone who is not entirely sane. Perhaps it is the fact that they can't see each other's faces that makes the conversation especially unsettling - the intensity of it, the rush of words from someone she has never met before, from a person who, though voluble, she can no longer see.

The man begins to unfold his conviction that the world is ruled by a species of lizard with the ability to change its shape into that of humans. The Queen is a lizard, apparently. All the country's current politicians are too. Elsa decides after all that she is glad that neither of them can see the other. She imagines her face betrays the mixture of fear and bewildered amusement that, listening to him, she increasingly feels.

That Professor Whitty, she hears the man say next, he's one, but he's really bad at transforming. And to her own dismay as she sits there in the darkness, in the middle of a lockdown that no one ever saw coming, in the kitchen of a man who is running an illicit sunbed parlour in the middle of a town in the West of England - that is to say, as she sits there in a real and yet entirely unbelievable situation - a horrible thought creeps into Elsa's mind.

What if he's right?

But then the lights come on again, and Xan is released from her sunbed and they leave Ottery St Mary, without being waylaid by the cops.

They continue breaking the law though - back in town, Xan doesn’t drop Elsa off and head straight on to her own home. Instead, she accepts Elsa’s invitation to come into her house and have a drink. They spend the rest of the evening in each other’s company, which, as anyone from the government will tell you, is a serious offence. They drink wine and eat crisps and watch television together, deep into the night.

Hardened criminality is easier to slip into than you'd think in these strange times.