|

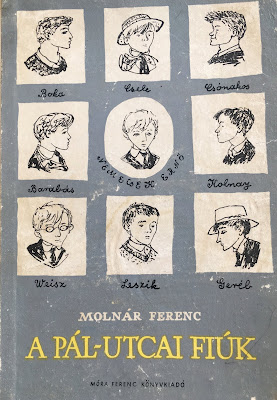

| I found my copy in a junk shop - very battered, printed in Romania, with enchanting illustrations, but no mention of who the illustrator was |

I find it hard to explain to people who don't enjoy learning languages what it is about the activity that I find so endlessly appealing. I am not good at languages, I don't find them easy to pick up, so why do I bother?

It isn't so that I can converse - I find that being able to speak a language is always the last thing that I manage, mainly because the whole business of conversation, even in my own language, is always the use of language that is most fraught with nervous tension, because one has to be quick and not bore people, et cetera et cetera.

For me, the main aim - or certainly the first aim - is to be able to read books in the language I'm learning, then maybe listen to the radio, watch the television, maybe even go to the theatre.

In this context, I'm very excited to have at last finished reading my very first book in Hungarian (with enormous help from the dictionary and some from Google Translate). I have to admit it is only a children's book, but on the other hand it is also one of the best books I've ever had the pleasure to read.

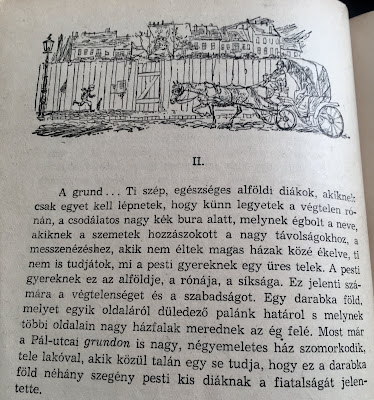

The book concerns a group of schoolboys who live in the vicinity of Pal Street in the VIIIth district of Budapest. At the start of the book the boys have staked out a small empty space on Pal Street as their own special territory. Here is Molnar's introduction of the "grund" to the reader:

with my rough translation:

"The grund. Oh you fine strapping kids who live on the Great Plain, you're able to step out of your front doors straight into a boundless plain. It spreads out in front of you, beneath the marvellous vast blue dome of the sky, and your eyes are used to its great empty distances and far horizons. You don't have to live wedged in between high buildings and so you have no idea what an empty plot of ground is like for a bunch of kids living in the middle of Budapest. For them, their little scrap of land is the Great Plain, their endless distance, their wide blue yonder. That patch, bordered on one side by a tumbledown fence and on the other by buildings reaching skywards, is for them limitless and comes with the promise of freedom. These days a big melancholy four-storey building stands on the Pal Street "grund", full of apartment dwellers, among whom there is probably no-one now who has any inkling of how much that particular little plot once meant to a few poor Budapest children in their youth."

Having been well-schooled in The Return of the Native and having had to answer a question in some exam somewhere about whether Egdon Heath can be considered a character in that novel, I couldn't help seeing parallels. However, unlike Hardy, Molnar doesn't start the book with a description of the book's most important setting. Instead, he begins by conjuring up marvellously an afternoon in a fourth-form gymnasium classroom where the pupils are looking forward to being let out at the end of the day. He introduces us to our main heroes and their tiny preoccupations and paints a picture of the universe in which they exist.

Once school is finished, the news arrives that there is a challenge to the group's hold on the "grund". From this unfolds a tale over several days of desperate struggles, betrayal, heroics and daring. It sounds so trivial but, because Molnar is brilliant and his understanding of humanity and characterisation are both brilliant, it is anything but. The reader - well this one - becomes deeply involved with the characters and their fates.

The story ends in tragedy, but includes much humour, particularly regarding the lack of a sense of absurdity among many humans however young they may be - the minutes of the Putty Club and its antics are wonderfully pompous. The book seems to me to be an allegory, the noble Pal Street boys being a people, the grund a nation, the cause freedom, and all of this set within the higher power of the school and Professor Rácz, who is the deity above the fray. The final twist strikes me as particularly Hungarian - and only when it comes and you look back do you realise that Molnar had warned you in advance and there ought to have been no surprise.

|

| Something rather Arthur Ransome-esque about this, but the book is infinitely deeper than anything by Ransome |

|

| You can still glimpse inner courtyards like this in Budapest's outer VIIIth |

No comments:

Post a Comment