Having gone from stupidly panicked & uninformed disapproval of Sweden’s approach during the so-called pandemic to an understanding that their approach was the right one, I was intrigued when I saw Tweets about an article that looks at what happened in Sweden & how little the Swedish experience is being reported by any international media. As the article was only in Swedish, I decided to run it through Google Translate & I am putting the result here for those who might be interested

The author of the article is Johan Anderberg & the original piece can be found here.

The disaster that never came

1 November 2021 19:03

Sweden's low death toll is an uncomfortable truth for the media and those in power in several countries. They show that millions of people have lived in deprivation to no avail.

Exactly one hundred years ago, a large demonstration took place in New York.

It was a summer day in 1921. July 4, to be precise - United States National Day.

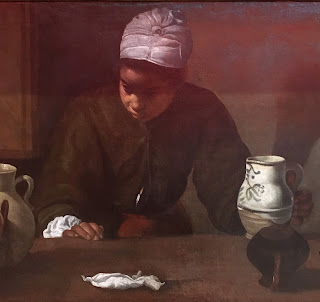

Between two o'clock and four o'clock in the afternoon, 20,000 people walked down Fifth Avenue. They sang, chanted and held up placards. On one of them appeared Leonardo da Vinci's painting "The Last Supper" - with the text: "Wine was served".

"Tyranny in the name of justice is the worst of all tyrannies," another poster read.

"Cheers for beer," shouted a gray-haired woman, according to a report in the New York Times from the next day.

What happened that day was the result of one of the greatest public health policy experiments ever. For a year, beer, wine and spirits had been illegal throughout the United States. Thanks to an amendment to the US Constitution, all production, transportation and sale of alcohol were banned.

From a public health perspective, it appeared to be a reasonable measure. It was clear that alcohol was a dangerous substance. Illness, violence, poverty and crime were intimately linked to the drug.

As so often in the history of democracy, Americans now wrestled with the balance between freedom and security. Was it really right to prevent free people from making drinks that they not only appreciated, but that were also important for cultural and religious reasons?

The protesters who went south in Manhattan that day had their opinion clear. This was an anti-democratic invention. The posters referred to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln. This is not how it would be in a free society.

Twelve years later, the experiment was over. In 1933, alcohol became legal again.

But it was not because the libertarian arguments had won. It was not because those protesters were suddenly heard for their opinions.

Nor was it because the drug itself was considered less harmful to health.

The reason why the alcohol ban ceased to apply was because it simply did not work.

It no longer mattered whether alcohol was dangerous or not. It did not matter what political opinion one had.

If it did not work, then it did not work.

Because no matter what the law said, Americans did not stop consuming alcohol. Drinking was simply moved from bars to "speakeasies", people learned to burn their own alcohol, smuggling from Canada became a popular sport, and the American mafia found a new source of income.

Today, most people agree that the experiment - "the noble experiment", as American historians call it - was a gigantic failure.

Until a little more than two years ago, the American alcohol ban was the largest social engineering experiment a democracy has ever undertaken.

But then it was 2020.

At the beginning of that year, a new virus began to seep out of China. And the whole world began a new experiment.

Faced with the threat of a new coronavirus, the world's rulers invented completely new measures to prevent the spread. By closing schools, by banning people from meeting, by forcing entrepreneurs to close down their businesses, by forcing citizens to wear masks, the idea was that lives could be saved

Just as during the "noble experiment" in the United States, this experiment also created a debate. In all the democracies of the world, freedom was weighed against what was perceived as security. Individual rights stood against what was considered best for public health.

The path that Sweden chose stood out in several ways. For the citizens of the country, it was most clearly noticed by the fact that they largely did not have to wear masks, that the younger children went to school and that their activities were largely allowed to continue unhindered.

Some groups had their lives or livelihoods cut disproportionately: high school students, people over the age of 70, employees in the restaurant industry.

But there was no doubt that the Swedes lived freer than others.

So how did it really go?

Eleven years after that demonstration in New York, the US Supreme Court ruled in a lawsuit that came to be known as the New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann.

It was not about alcohol. It was not really about something that is particularly interesting today. It was about whether Oklahoma was entitled to require a special license from companies that sold ice in the state.

No, the court said. Everyone who wanted to could sell ice cream.

So that was it. And probably the obscure dispute would have fallen into oblivion rather quickly if it were not for a dissenting opinion that one of the nine judges wrote down and added to the verdict.

The judge's name was Louis Brandeis and he wanted to draw the other lawyers' attention to what he called a "happy circumstance" in American democracy.

"A brave state can," he wrote, "if its inhabitants so wish, function as a laboratory and test new social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country."

The year was 1932, and Brandeis described the revolutionary scientific leaps that the Western world had produced in a short time: “the discoveries in physics, the triumphs of innovation, show the value of trial and error. To a large extent, this progress is due to experimentation. ”

So why would a democracy give up the same opportunity to learn, to improve, to make the lives of its citizens better?

To experiment simply.

Brandei's thought figure has since come to be known as "the laboratories of democracy". If you are a political scientist, you may prefer to call it "institutional competition", but the idea is the same: bad ideas are eliminated and slowly replaced by better ones. Thanks to the United States' failed attempt to ban alcohol, no democracies have attempted it since.

They did an experiment. And we took advantage of it.

It's almost hard to remember it now, but for most of 2020, the word 'experiment' had a negative connotation. It was one that we Swedes were exposed to, when we - compared to the rest of the world - maintained some form of normality.

This experiment was condemned by the outside world early on as "a disaster" (Time Magazine), a "moral history" (New York Times), "deadly folly" (The Guardian) and so on. The more influential a newspaper was, the stronger the invective seemed to become. In Germany, Focus called it all "laxity", Italian La Repubblica said that "the Nordic model country" made a dangerous mistake.

That's what it looked like.

The description of the Swedish line as an experiment was not really wrong. In both theory and practice, Swedes lived very differently compared to, above all, Americans and other Europeans.

One could object that it was Italy, France, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom and the other countries that were conducting an experiment, that they were testing completely new ways to prevent the spread of a virus.

But the word choice is less important. It is clear that Sweden chose one path, the rest of Europe another.

One could see it as if the outside world formulated a hypothesis. It was that freedom in Sweden would be costly.

The absence of restrictions, the open schools, the reliance on recommendations in violation of laws and police interventions, would result in higher death rates than in other countries. And - consequently - that the freedom that the citizens of the other countries experienced would save lives.

Many Swedes agreed with that hypothesis. "Shut down Sweden to protect Sweden," wrote Dagens Nyheter's Peter Wolodarski, who in his double power of both opinion leaders and head of Sweden's most influential newsroom, must be described as the country's most powerful journalist.

He was far from alone in demanding a tougher grip. Renowned infection control experts, microbiologists, epidemiologists - from all over the country were warned of the consequences. Researchers from Uppsala University, Karolinska Institutet and the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm connected supercomputers and calculated that 96,000 Swedes would die before the summer of 2020.

At this time, it was not an unreasonable theory that Swedish freedom was expensive. In the US, with its powerful shutdowns, the death toll - measured per capita - was significantly lower than in Sweden throughout the spring of 2020. And on the sites where the ravages of the pandemic could be followed in real time - such as Our World in Data, Johns Hopkins University database or Worldometer - it was clear that Sweden had higher death rates than most other countries.

But the experiment continued. During the year that followed, the virus ravaged the world and several of the shut down countries now passed Sweden's death toll - one by one.

Britain, USA, France, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic, Hungary, Spain, Argentina, Belgium - countries that blocked playgrounds, forced their children to wear masks, closed schools, fined citizens for hanging on the beach, guarded parks with drones - all have been hit worse than Sweden.

At the time of writing, over 50 countries have a higher proportion of deaths in covid.

If you measure excess mortality for the whole of 2020, Sweden, according to Eurostat, will end up in 21st place out of 31 European countries.

This fact must be one of the world's most underreported news. Considering all the articles and TV features that were made about Sweden's foolishly liberal attitude to the pandemic a year ago, considering how certain data sources were daily referenced in the world media, it is strange that the same sources today seem completely uninteresting.

Therefore, there is now a bit of a charade going on in the world media; it is as if Sweden does not exist. When the Wall Street Journal published a report from Portugal this week, it was described as if the country could "give a glimpse" of what it was like to live with the virus. This new life meant, among other things, vaccine passes and masks at large crowd events such as football matches.

Not a single place in the report mentioned that people in Sweden could attend football matches without wearing masks. Not in one place was it said that Sweden - with a smaller proportion of dead than Portugal since the start of the pandemic - had ended virtually all restrictions.

The Wall Street Journal is far from alone in its selective reporting. The New York Times, The Guardian, the BBC, The Times - they were all once so hungry for lockdowns that today it is impossible for them to falsify their original theories.

Johan Anderberg is a journalist and author of the book "Flocken" about Sweden's pandemic strategy.