While in London after Christmas I went to look at the exhibition of works by Durer that they've put together at the National Gallery. I cannot do it as much justice as the excellent review by Michael Prodger in the New Statesman, reproduced below, (the detail about the unforgiving nature of the technique called silverpoint especially interested me). However, I took some photographs on my mobile telephone of the works I liked best or those that intrigued me, and some of these might provide a glimpse of what's on offer, for those unable or unwilling to visit the gallery themselves.

This lion appears near the start of the exhibition, and is one of the earlier works by Durer on show. It normally lives in the Hamburg Kunsthalle and is gouache on parchment, heightened with gold. Durer made it in 1494. The National Gallery says that the image seems heraldic, more like something from an illuminated manuscript than a picture in its own right, and that the movement of the lion's four legs is unconvincing, adding that Durer didn't have an opportunity to see a real lion until he went to the Netherlands in 1520-1.

This next picture isn't something I covet (it is unsophisticated to do so, but I very often look at pictures with an eye to whether I'd like to have them in my own house or not), but it is interesting, because it isn't what I'd grown to expect as a typical Durer picture:

It is called Trintperg - Dosso di Trento and it usually lives in the Kunsthalle in Bremen. It is a watercolour and Durer made it in 1495. The wall note says: "The focus of Durer's interest is the massive rock formation on which the city of Trent (now in Italy) is situated, seen from the bank of the river Adige. Although he includes some identifiable buildings, Durer omits the surrounding hills. He does not represent any human life, but has closely studied the reflections of the surface of the water. This watercolour was presumably worked up in the studio from sketches made outdoors."

This one, called A Sparrowhawk and dated around 1510 isn't actually by Durer, but by Jacopo de' Barbari who was active between 1500 and approx 1516. The wall note tells us that Durer first encountered this Venetian painter and printmaker in Nuremberg in 1500. Barbari's engravings of nudes apparently inspired Durer. He wanted to understand how Barbari conveyed proportion but wrote that Barbari "did not want to show his principles to me clearly". This small painting may be a fragment from a larger work, but I like it a lot anyway, partly because any domesticated bird of prey makes me think of

The Pilgrim Hawk, a novella I am fond of. The picture is part of the National Gallery's own collection.

This is Saint Catherine, by Durer, made in about 1494. The wall note reads as follows:

"Saint Catherine kneels to receive a wedding ring from the infant christ, sketchily indicated on the right beside his mother's knee. This closely hatched drawing may follow a painted composition of the Virgin and Child with saints that Durer had seen, or it was possibly made from a model. The saint's dress resembles that worn by Venetian women shown in other studies by Durer so he probably made this drawing in Venice." It is made with a pen in light grey ink and comes from a collection in Cologne.

These statuettes of Adam and Eve are made of glazed boxwood and they are by Conrad Meit, who was active from about 1480 to about 1550. They were made in 1515. They are kept in the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein Gotha. The wall note tells us: " Conrad Meit was sculptor to Margaret of Austria. Durer admired his work, calling him the "fine sculptor" and sent him presents of several of his prints. These two are inspired by Durer's engraving of Adam and Eve. Eve's right arm is very similar to Durer's image, while the proportions and balance of the figures owe much to Durer's studies of the human body." In the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in the Schatzkammer I first noticed how marvellous the detail of tiny wooden sculptures can be. These struck me as exceptional.

These dear babies were drawn by Durer before 1513, using ink on paper. They are part of the collection of the British Library. The gallery note says: " After his return from Venice, Durer further refined his study of human proportions. He moved away from the Roman writer Vitruvius' ideal of the 'well-shaped man' and the norms of ideally proportioned bodies. He wanted to study and understand the varieties of the human form, stating that he would leave it to God to judge beauty."

This painting is from Vienna, although I don't think I've ever seen it hung there. It is called The Feast of the Rose Garlands and Durer painted it, using oil on canvas, between 1606 and 1612, allegedly in part to prove he could use colour. It was commissioned for the church of the German merchants in Venice, San Bartolomeo. To the left of the Virgin and Child is the Pope, to the right the Emperor Maximilian. You can see Durer himself standing by the bare tree at the right.

The next picture, made with brush and black ink and wash, with white opaque watercolour and pen and dark ink on blue paper, is usually kept in the Morgan Library and Museum, New York. It is a study for the kneeling figure in blue on the right of The Virgin of the Rose Garlands and it was made in 1506:

These next few drawings are taken from sketchbooks of Durer's and I particularly liked them, as I felt that looking at them was a bit like reading little bits from his diary, very immediate, giving a sense that one is looking through a window and glimpsing moments in his daily life:

Durer wrote about this one: "This is my landlord in Antwerp Jobst Plankfelt 1520." Plankfelt was the landlord of the inn where Durer lodged for much of his stay in the Netherlands. It stood between the harbour and the main market. In August 1520, he noted "my landlord I have also drawn a likeness of, that is Jobst Plankfelt, he gave me a branch of white coral." The picture normally lives in the Staadel Museum in Frankfurt and is done with pen and brown ink on paper.

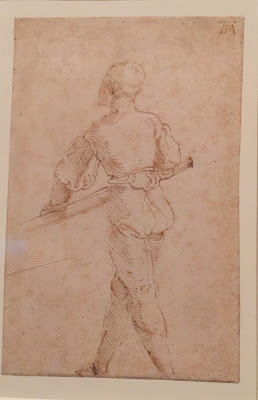

The National Gallery curators think that this sketch might have been done by Durer after seeing men ferrying passengers across a river as, travelling to the Netherlands, he often went by riverboat. It seemed to me to give a very strong sense of seeing something alive, something that is part of a scene that was real and part of Durer's experience, thus of looking back directly into the past.

This one is called The Beautiful Young Woman of Antwerp. In fact the man on the left was drawn first and is probably an Augsburg merchant who travelled with Durer to Zeeland. His name was Markus Ulstett and Durer mentions drawing him around December 1520. Both these sketches are made with silverpoint on ivory coloured prepared paper, and they normally live in the Stadel Museum in Frankfurt

I love these two drawings because they conjure up someone who seems a vivid personality even hundreds of years later. His name is Imperial Captain Felix Hungersperg and Durer's inscription to the first of the two reads "This is Captain Felix the exquisite lutenist, done at Antwerp 1520". In his diary for November 1520 he says, "I did a pen drawing of Felix kneeling. He gave me a hundred oysters". Both drawings are part of the Albertina collection in Vienna and are made with pen and brown ink.

There were many other wonderful works, including some very moving ones of Christ -

and some wonderful portraits:

(mind you my favourite of the portraits was not by Durer but by Lucas van Leyden, who, the gallery curators assert, was much influenced by Durer):

but this post is getting long, so I will finish with my absolute favourite thing in the whole exhibition which is this series of nine studies of Saint Christopher, made in 1521. There just seems to me such movement and life in the thing, the saint becomes more and more hard pressed, the baby more demanding. Made in 1521, it belongs to the Staatliche Museum in Berlin:

These music making angels from 1521, studies for an altarpiece, also won my heart. They can usually be found in the Met in New York:

The New Statesman’s view:

“In 1520 Albrecht Dürer was in Brussels when the contents of a treasure ship sent back from the Americas by Hernán Cortés were put on display to celebrate the coronation of Charles V. The cache contained, among other items, obsidian weapons, jaguar pelts, feathered shields, gemstones and mosaic pieces, and gold wrought in innumerable inventive ways. Dürer, the son of a Nuremberg goldsmith, was flabbergasted. “All the days of my life I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things,” he wrote, “for I saw amongst them wonderful works of art.” But then, for him, everything was a work of art – either God-made or man-made. His well-known watercolours of a piece of turf and the iridescent wing of a blue roller bird are themselves marvels of creation that show marvels of creation.

For Dürer, even more than for most artists, the world was a place of wonder. If Leonardo da Vinci, his senior by 19 years, looked longest and deepest at natural phenomena – from the flow of water to the action of veins and sinews – Dürer (1471-1528) was in thrall to materiality, where sight became an extension of touch.

Dürer’s visual omnivorousness is on display everywhere in the National Gallery’s “Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist”, an exhibition that traces the four main trips undertaken by the artist during the course of his life. He was a wide-eyed traveller along the Rhine, to Venice twice and to the Low Countries, and what he saw along the way inevitably emerges in his art.

Almost everything he encountered was a novelty and nothing was beneath his notice. A tumbled mountain hut that gave him respite during his crossing of the Alps is recorded in a small watercolour, each stone and fallen rafter carefully differentiated. The dizzying heights of mountain passes are there in his etching Nemesis, depicting the Greek goddess, which is manic with tiny details of pine tree, crags and villages far below on the valley floor. The outfits worn by Netherlandish women are carefully recorded, down to the smallest fold and nap of fur. The animals he saw in the royal menagerie in Brussels – lion, lynx, baboon – are shown dozy or indolent (he had depicted lions for years before he ever saw a real one, and gave them near-human faces). Even an enema syringe is recorded, peeking out from the folds of the seated angel’s robe in his celebrated Melencolia I etching: its meaning, like so much about the print, is unknown, but he did record that he had an Antwerp apothecary’s wife administer a purge while he was visiting the city.

Of course, his travels were about people too, and the exhibition is also a record of friendships made. In 1492 he headed to Colmar to meet and learn from the printmaker Martin Schongauer, but by the time he arrived Schongauer had just died. He had better luck on his two journeys to Venice, in 1494-95 and 1505-07, where he met numerous painters, growing close to Giovanni Bellini and corresponding with Leonardo and Raphael. “I was amazed by the subtle ingeniousness of people in foreign lands,” he wrote, and said of Bellini that “he is very old yet still the best at painting”. The Venetian returned the admiration in a jokey homage by painting the cropped rump of a cow in his The Assassination of St Peter Martyr, circa 1505-07 (from upstairs in the National Gallery), which he lifted from Dürer’s engraving of The Prodigal Son, circa 1496. Jan Gossaert would do something similar by taking one of the hunting dogs in Dürer’s St Eustace engraving (1500-01) and relocating it to the foreground of his Adoration of the Kings (again in the National’s collection) of 1510-15

Not that Dürer always felt at home on his travels. One reason for his second trip to Venice may have been to deal with the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, who had established a lucrative line in counterfeiting Dürer’s prints, complete with the “AD” monogram. And when, in 1506, Dürer won a commission to paint an altarpiece for the republic’s German community, he filled it with colour as a riposte to local artists (“to shut their mouths”) who felt he could only, albeit brilliantly, work in black and white. Nevertheless, he won acceptance and wrote home: “O, how cold I will be away from the sun; here I am a gentleman, at home a parasite.”The best-documented of his journeys is the tour of the Low Countries he carried out in 1520-21 in an attempt to petition the new Holy Roman Emperor for a continuation of the stipend he had been paid by the previous emperor, Maximilian I. He travelled with his wife Agnes, their maid Susanna, and a sheaf of prints to gift or barter, and he kept a journal of the trip in which he also recorded their expenses (13 porpoise bristle brushes, two parrots in a cage, an ivory skull…). He was feted along the way and the exhibition contains a fabulous selection of the 140 drawings – 47 of them in charcoal – he made on the trip of people he met, including his Antwerp innkeeper. Many of the sitters’ names have been lost, and not all of them paid: “Item: Six people have given me nothing for doing their portraits in Brussels,” he noted. They are nevertheless vivid memorials, with their heads and shoulders set off against dark backgrounds and the handling varying in finesse, from fine to broad, within the same image.

Two portraits in particular demonstrate his preternatural facility. One is a silverpoint (made using a metal stylus on chemically treated paper – a technique that did not allow for corrections), possibly of the painter Jan Provoost. It is a drawing of the utmost delicacy, composed of hatchings and a seemingly infinite number of lines – flicked, curled, extended, barely there. The other, a painting lent by the Prado in Madrid, shows a stern, middle-aged man with a fur collar and large hat. It has a degree of meticulous detail – downy chin, eyebrow hairs, highlighted curls – that declares how aware Dürer was of the earlier Van Eyckian tradition of Low Countries art and his keenness to show that he too was a master of this miniaturist manner. Both sitters are treated as material as well as men, with their skin and hair offering him fresh textures to add to those of their apparel.

Among these faces, and the many portraits included from artists in his circle such as Quinten Massys, Bernaert van Orley and Lucas van Leyden, the physiognomy that is missing is Dürer’s own. He was one of the most prolific and daring of self-portraitists, depicting himself at least 13 times in different media – one of which, according to Giorgio Vasari, was “painted in watercolour on very fine linen, so that it showed equally on both sides” and was sent as a gift to Raphael. Not one of these is in the exhibition to show what this man, so proud of his golden hair and his abilities (“Why has God given me such magnificent talent? It is a curse as well as a great blessing”), looked like as he criss-crossed Europe. His face would have moored a narrative that sometimes loses focus.

When Dürer returned to Nuremberg in 1521 he brought back something else alongside the gewgaws he had purchased. Somewhere in the Low Countries he contracted an illness, probably malaria, that was to stay with him and that contributed to his death in 1528, at 56. For the inveterate traveller and chronicler of tangible things, it was an invisible but fatal souvenir.”

Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist

National Gallery,

London WC2, until 27 February