Thursday, 31 May 2012

Words and Phrases - an Everyday Story of Pedantic Folk

A friend baffled me the other day by saying she had to have a 'procedure'. Eventually, we worked out that she was going to have what used to be called an operation - or 'op', as in, 'The quack reckons I need an op on my bunions, but I reckon I can struggle on for a year or two more.'

Where did this 'procedure' thing come from? When I hear the word used in the medical context, I immediately assume they're going to tattoo the council by-laws on dog fouling across my lower abdomen (and there's a horrid word, 'abdomen', don't know why I'm using it - this medical jargon is clearly infectious).

Although, speaking of infections, I'm never going to pick up the virally spreading usage that is 'medication' - what the hell is wrong with the perfectly good word I've used all my life, namely 'medicine'. 'A spoonful of sugar helps the medication go down' doesn't have quite the same ring to it, in my opinion - ditto 'Laughter is the best medication'. Ugh, ugh, ugh

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

Battered Penguins - The Case of the Late Pig

As I think I have already conveyed in an earlier post, I love Margery Allingham. I've loved her from the first moment I opened one of her books, but I've loved her even more since I read a short biography of her, which suggested she had a far from easy love life and died a pretty miserable death. How could this be, when she was both funny and wise - and wrote so beautifully?

Allingham's best known creation is Albert Campion, an enigmatic figure, who dabbles in detective work - describing himself thus: "I am not one of these intellectual sleuths, I am afraid. My mind does not work like an adding machine, taking the facts in neatly one by one and doing the work as it goes along. I am more like the bloke with the sack and spiked stick. I collect all the odds and ends I can see and turn out the bag at the lunch hour" - and has a rather large, redeemed ex-criminal as his man-servant, a fellow called Lugg who, as Campion puts it, 'in spite of magnificent qualities has elements of the Oaf about him'.

In The Case of the Late Pig Campion emerges a tiny bit from his usual mysteriousness by telling the story in the first person - although readers hoping for any real self-revelation will, I should immediately point out, be fairly disappointed. One thing one does learn, however, is that as a child he had a 'collection of skeleton leaves'; another is that he is, despite his reservations, quite devoted to Lugg. In addition, we discover that he was once smitten by a girl called Janet who he has known 'on and off, for twenty-three years. When I first saw her she was bald and pinkly horrible. I was almost sick at the sight of her, and was sent out into the garden until I had recovered my manners.'

As must be obvious from the above, we are not dealing here with an angst-ridden, hard-boiled gumshoe. Angst and hard-boiledness are not at all what Allingham's books are about - or at least not overtly. Instead of grit and horror, what you get in a Campion story is humour and wisdom. While the thread of the mystery ambles through the text, giving it a beginning, middle and end, we do not feel a tremendous urgency about finding its solution. Whodunnit is the genre but it is not what really holds the reader's - or this reader's anyway - main attention.

Instead of excitement and a desperate need to find out the name of the perpetrator, what carries you along in these books is the pleasure of the scenery you pass through. Allingham conjures up a Wooster-like world, full of buildings topped with parapets that 'finish off the flat fronts of Georgian houses and always remind me of the topping of marzipan icing on a very good fruit cake' or fronted by 'great white pillars ... built by an architect who had seen the BM and never forgotten it' - each one 'a millstone round somebody's neck' - and peopled by characters such as 'Guffy Randall' and 'Lofty, who is now holding down his seat in the Peers with a passionate determination more creditable than necessary'.

Onto this framework - and that of the murder story - Allingham then throws amusing observations and rather lovely descriptions such as the ones that follow, switching in tone between flippant and elegiac without apparent effort:

"A funeral is an impressive business even among the marble angels and broken columns of civilization. Here, out of the world in the rain-soaked silence of a forgotten hillside, it was both grim and sad."

"Even at twelve and a half Pig had had several revolting personal habits."

"It is about as easy to describe Whippet as it is to describe water or a sound in the night ... I don't know what he looks like, except that presumably he has a face, since it would be an omission that I should have been certain to observe. He had on some sort of grey-brown coat which merged with the dead cow-parsley and he looked at me with that vacancy which is yet recognition."

"Leo had very bright blue eyes which, like most soldiers', are of an almost startling innocence of expression."

"...it struck me then as odd that the boy should really be so very much the father of the man. It's a serious thought when you look at some children."

"No English country house is worthy of the name if it is not breathtaking at half past six on a June evening..."

"...the sweet cool fragrance of old wood and flowers which is the true smell of your good country house..."

She adds in exchanges like this one, which reminds me of the kind of conversation I would sometimes have with my father, in which for a moment I glimpsed whole orders of until-then hidden rules for life:

"'What were you playing? Bridge?'

Leo looked scandalising. 'Before lunch? No my dear boy. Poker. Wouldn't play bridge before lunch.'"

Last but not least, she chucks in a villain, who, given her obvious conservatism, (and I should point out that I don't use that word in any kind of hostile way), it is hard not to recognise as such, long before his culpability is eventually confirmed:

"He was a red-hot innovator, we discovered. He spoke with passion of the insanitary condition of the thatched cottages and the necessity of bringing culture into the life of the average villager, betraying, I thought, a lack of acquaintance with either the thatched cottage or, of course, the villager in question, who, as every countryman knows, does not exist."

A wrong un, clearly. Case closed.

Tuesday, 29 May 2012

Bilding the Edukashon Reverlushion

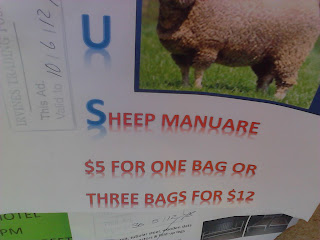

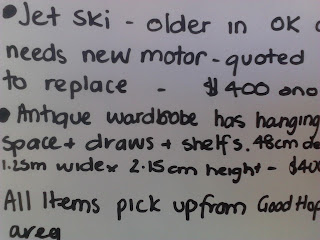

In my mother's local town this morning, I was glad to see so many signs of Australia's rapidly improving educational system:

(presumably the table became soild because they stored the manuare on top of it?)

(One artist in the family's plenty - I don't need a cupboard that draws).

(presumably the table became soild because they stored the manuare on top of it?)

(One artist in the family's plenty - I don't need a cupboard that draws).

Monday, 28 May 2012

Staying Cheerful

Before I went to live in England for a few years, I actually believed that a very significant proportion of the British population did inhabit enchanting villages where there were very few cars, no chainstores - but always at least one flourishing pub and usually a good village shop/post office plus an antique and/or bookshop - where foxgloves were eternally flowering and women spent much of their time cycling to and from sorting out the church hymn books, riding old-fashioned bicycles with wicker baskets.

Despite the gruesome events at the centre of each episode, the impression created by television series like Midsomer Murders, Rosemary and Thyme, Morse, its successor, Lewis, et cetera et cetera, is that rather than there being the odd, self-consciously lovely, much-flagged-in-the-tourist-books village here and there, there are lots and lots of them. Viewers come away with the idea that masses and masses - perhaps the great majority - of English people enjoy cozy lives in pretty, harmonious (apart from the odd, distressing but, in plot terms, necessary murder) communities, where the churches are still well-attended each Sunday and, rather than most of the villagers being time-poor commuters who barely spend any time in the place, everyone is in and out of each other's houses and everyone knows everyone else.

When I'd spent a bit of time in Britain, I realised that this was an illusion. At first I thought it was an illusion created to please foreigners but after a while I began to wonder whether it wasn't actually an illusion intended for domestic consumption. If you actually have to live in contemporary Britain, it is comforting to watch programmes depicting the kinds of villages that are shown in Midsomer Murders and to pretend to yourself that this image of your nation is actually real.

I thought of this the other day, when I heard Will Self say that he thought the most longlasting legacy left behind by Britain in the regions of its former empires was the habit of hypocrisy. I remembered then that, according to Harold Nicholson, hypocrisy fulfils for the British the same purpose as, I believe, Midsomer villages.

'Our hypocrisy,' said Nicolson, intending by his use of the first person plural to encompass not humanity but the English in particular, 'derives not from any intention to deceive others but from an ardent desire to comfort ourselves.'

Despite the gruesome events at the centre of each episode, the impression created by television series like Midsomer Murders, Rosemary and Thyme, Morse, its successor, Lewis, et cetera et cetera, is that rather than there being the odd, self-consciously lovely, much-flagged-in-the-tourist-books village here and there, there are lots and lots of them. Viewers come away with the idea that masses and masses - perhaps the great majority - of English people enjoy cozy lives in pretty, harmonious (apart from the odd, distressing but, in plot terms, necessary murder) communities, where the churches are still well-attended each Sunday and, rather than most of the villagers being time-poor commuters who barely spend any time in the place, everyone is in and out of each other's houses and everyone knows everyone else.

When I'd spent a bit of time in Britain, I realised that this was an illusion. At first I thought it was an illusion created to please foreigners but after a while I began to wonder whether it wasn't actually an illusion intended for domestic consumption. If you actually have to live in contemporary Britain, it is comforting to watch programmes depicting the kinds of villages that are shown in Midsomer Murders and to pretend to yourself that this image of your nation is actually real.

I thought of this the other day, when I heard Will Self say that he thought the most longlasting legacy left behind by Britain in the regions of its former empires was the habit of hypocrisy. I remembered then that, according to Harold Nicholson, hypocrisy fulfils for the British the same purpose as, I believe, Midsomer villages.

'Our hypocrisy,' said Nicolson, intending by his use of the first person plural to encompass not humanity but the English in particular, 'derives not from any intention to deceive others but from an ardent desire to comfort ourselves.'

Sunday, 27 May 2012

It's Later than I Thought

After reading George, at 20011, who was wondering if the word 'ersatz' will mean nothing to our children, I met up with a Hungarian friend for a meal. She was in Budapest recently and was surprised by an 11-year-old nephew who,after listening to the adults talking about what she had considered quite recent family history, asked, 'What does it mean, this thing you say Uncle Laszlo and Auntie Tunde did? '

'What thing?' the adults asked, trying to recall what exactly they had been saying.

"'Defect"- you said they "defected"- what is that? What does it mean?'

'What thing?' the adults asked, trying to recall what exactly they had been saying.

"'Defect"- you said they "defected"- what is that? What does it mean?'

Saturday, 26 May 2012

Peter Porter on Shakespeare

To distract myself from fretting about Shakespeare's great words being presented thus by the Globe Theatre:

- (That's Troilus and Cressida, don't you know) -

I turned again to The Best Australian Essays (a Ten-Year Collection) and started to read Peter Porter's essay, called The Old Good Books *. Here's what he has to say about Shakespeare:

"Shakespeare ... is everything. The church, rather than the academy, should sanctify him ... To this day, what Bottom tells us about his dream is the only notion of felicity I have ever believed in. 'I have had a dream past the wit of man to say what dream it was ... Methought I was - there is no man can tell what. Methought I was - and methought I had - but man is but a patched fool if he will offer to say what methought I had.' Bottom goes straight to Heaven, and Titania and Oberon linger in the world of their all-too-ubiquitous magic. I still see the play as I saw it then. A magical starburst of words.

The only possible maturity I have come to in my reading of Shakespeare (and watching his plays being acted) is of a widening of my sense of wonder. The more you put yourself in Shakespeare's world, the more you become a connoisseur of brilliance. Once I would have gone for the extremities of Macbeth, Hamlet and Lear. Today, you are more likely to find me luxuriating in Love's Labour Lost. Moth looks at the verbal show-offs in that play with affection and cool assessment. 'They have been at a great feast of languages, and stolen the scraps.' The frissons spring up momentarily in the middle of so much disputed action. 'Why all the souls that were were forfeit once,' says someone in Measure for Measure. Those looking-over-the-fence 'weres' are worth giving your life for. As Michelangelo told a patron of Raphael's who complained about the fee charged for a painting of Isaiah he'd commissioned, 'The knee alone is worth the price.' Throughout the corpus of Shakespeare the great moments survive and new ones keep arriving. The words of Palamon soliciting the aid of the goddesss Venus in The Two Noble Kinsmen are a perfect valediction of sexual love:

Thou that from eleven to ninety reignest

In mortal bosoms, whose chase is this world

As we in herds thy game, I give thee thanks

For this fair token; which being laid unto

Mine innocent true heart, arms in assurance

My body to this business."

Wise words, (I'm referring to Porter's on Shakespeare's, rather than Shakespeare's on sexual love [not that I'm knocking those]). If you need more convincing though, let me cite a single beautiful line - not even a full line, in fact - from Antony and Cleopatra to try to demonstrate why I think the Globe project is so mad. The line is "The bright day is done. And we are for the dark." What an exquisite phrase: each word is simple, everyday, monosyllabic, and yet it resonates. It is Shakespeare's almost unerring ability, seen in this example and in countless other instances, to choose the right words and to put them in the right order - apparently effortlessly - that makes him so extraordinary. For me at least, he appears to have been a man whose mind was more completely in tune with the English language than anyone else's ever has been. He had an uncanny feeling for our words. He handled them as if they were music. And that is why I think that, in an English-speaking country, presenting his plays in translation (let alone Hip Hop) is purely perverse.

Still, if you are more interested in novelty than the 'magical starburst of words' that is Shakespeare's greatest achievement, if you are in fact a modern day 'verbal show-off' who prefers 'scraps' from the 'feast of languages' to a dish that is perfect and whole, pop along to the Globe before 9 June for a dose of Shakespeare made incomprehensible to English speakers and served up instead in Swahili, Urdu, Albanian, Juba Arabic, Lithuanian, Gujarati, Yoruba, British Sign Language (Macbeth) or, yes, I promise, Hip Hop (Much Ado about Nothing).

*For more on Peter Porter, listen to my brother's interview with Clive James, which includes the latter's touching reminiscences about his old friend.

I turned again to The Best Australian Essays (a Ten-Year Collection) and started to read Peter Porter's essay, called The Old Good Books *. Here's what he has to say about Shakespeare:

"Shakespeare ... is everything. The church, rather than the academy, should sanctify him ... To this day, what Bottom tells us about his dream is the only notion of felicity I have ever believed in. 'I have had a dream past the wit of man to say what dream it was ... Methought I was - there is no man can tell what. Methought I was - and methought I had - but man is but a patched fool if he will offer to say what methought I had.' Bottom goes straight to Heaven, and Titania and Oberon linger in the world of their all-too-ubiquitous magic. I still see the play as I saw it then. A magical starburst of words.

The only possible maturity I have come to in my reading of Shakespeare (and watching his plays being acted) is of a widening of my sense of wonder. The more you put yourself in Shakespeare's world, the more you become a connoisseur of brilliance. Once I would have gone for the extremities of Macbeth, Hamlet and Lear. Today, you are more likely to find me luxuriating in Love's Labour Lost. Moth looks at the verbal show-offs in that play with affection and cool assessment. 'They have been at a great feast of languages, and stolen the scraps.' The frissons spring up momentarily in the middle of so much disputed action. 'Why all the souls that were were forfeit once,' says someone in Measure for Measure. Those looking-over-the-fence 'weres' are worth giving your life for. As Michelangelo told a patron of Raphael's who complained about the fee charged for a painting of Isaiah he'd commissioned, 'The knee alone is worth the price.' Throughout the corpus of Shakespeare the great moments survive and new ones keep arriving. The words of Palamon soliciting the aid of the goddesss Venus in The Two Noble Kinsmen are a perfect valediction of sexual love:

Thou that from eleven to ninety reignest

In mortal bosoms, whose chase is this world

As we in herds thy game, I give thee thanks

For this fair token; which being laid unto

Mine innocent true heart, arms in assurance

My body to this business."

Wise words, (I'm referring to Porter's on Shakespeare's, rather than Shakespeare's on sexual love [not that I'm knocking those]). If you need more convincing though, let me cite a single beautiful line - not even a full line, in fact - from Antony and Cleopatra to try to demonstrate why I think the Globe project is so mad. The line is "The bright day is done. And we are for the dark." What an exquisite phrase: each word is simple, everyday, monosyllabic, and yet it resonates. It is Shakespeare's almost unerring ability, seen in this example and in countless other instances, to choose the right words and to put them in the right order - apparently effortlessly - that makes him so extraordinary. For me at least, he appears to have been a man whose mind was more completely in tune with the English language than anyone else's ever has been. He had an uncanny feeling for our words. He handled them as if they were music. And that is why I think that, in an English-speaking country, presenting his plays in translation (let alone Hip Hop) is purely perverse.

Still, if you are more interested in novelty than the 'magical starburst of words' that is Shakespeare's greatest achievement, if you are in fact a modern day 'verbal show-off' who prefers 'scraps' from the 'feast of languages' to a dish that is perfect and whole, pop along to the Globe before 9 June for a dose of Shakespeare made incomprehensible to English speakers and served up instead in Swahili, Urdu, Albanian, Juba Arabic, Lithuanian, Gujarati, Yoruba, British Sign Language (Macbeth) or, yes, I promise, Hip Hop (Much Ado about Nothing).

*For more on Peter Porter, listen to my brother's interview with Clive James, which includes the latter's touching reminiscences about his old friend.

Thursday, 24 May 2012

Rip van Priestley

There are so many letters I have not written over the last decade - thank-yous, complaints, mere keeping-in-touch type things. Until I read this letter in the 10 May, 2012 issue of the London Review of Books, I thought it was too late to write them. Now I'm not so sure:

And what of Mr Priestley? Where has he been for the last 18 years? In the last spot on the globe unreachable by email or the postal system? In a coma? Or is his letter a cunning marketing ploy to get a second round of publicity for his magnum opus? There's a story here, I'm sure.

And what of Mr Priestley? Where has he been for the last 18 years? In the last spot on the globe unreachable by email or the postal system? In a coma? Or is his letter a cunning marketing ploy to get a second round of publicity for his magnum opus? There's a story here, I'm sure.

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

Maps, Old and New

I've been reading Good Behaviour by Molly Keane, (astonishingly good book, terrible and funny, charting the way that emotional deprivation ripples out through the generations, extending its damage ever further), and my mother and I were discussing it and other books about Ireland, over the telephone. Eventually we began to wonder where certain places in the books we were discussing were, and so I opened Google Maps on my laptop. However, before I could locate the town I was looking for, my mother said she'd found it. 'What map are you using?' I wondered. 'Oh, I'm using the tea towel your Aunt Bindy brought me back from her trip to see the gardens of Ireland 15 years ago,' she replied.

Tuesday, 22 May 2012

Haka-d Off

On Sunday, we went to see a production of Macbeth. It was not a very good production - in fact, it made me wonder whether there wasn't a case to be made for the mandatory presence at rehearsals of an outsider whose job it is to ask the director questions. For instance, in the case of the production we saw, the questions that I think needed to be asked were these:

That's the main reason I always enjoyed going to the Globe in London. To listen to the words of Shakespeare. Which is why I object to the current season's productions - here is an excerpt from this year's Troilus and Cressida at the Globe Theatre, to demonstrate what is being lost:

I leave it to the reviewer on Radio 3 to give his expert assessment:

If I hadn't heard the interviewer refer to him as Gabriel, I might have imagined that his name was Tim:

Here's Radio 3's Philip Dodd asking the question that is central to my objections to the Globe's multi-lingual season:

Here is the full excerpt from Radio 3, with the reviewers flailing as they try to answer that question and justify their right-on, emperor's new clothes excitement about the whole sorry project:

- Why have you decided to amalgmate the three witches into the body of one rather attractive young blonde woman, (and if it is simply because you want her to have a sex scene with Macbeth towards the end of the play, that is probably not a good enough reason - sexing up always ends in disaster, as Tony Blair et al could tell you)?

- Having chosen to have a single witch, why have you then decided to put her voice through one of those machines they use on current affairs programmes to disguise people's voices?

- Having chosen to have a single witch and to put her voice through a distortion machine, so that it's virtually impossible to catch a word she's saying anyway, why have you also decided to make her gabble most of her lines?

- Why have you decided to direct the main actor to adopt, whenever he is on stage, a posture that is a cross between someone getting in training for the ski season, (bending of the knees at all times) and someone hoping to be cast as the hunchbacked king in the company's next production of Richard III?

- Why have you decided to use an unaltering stage set that contains no props whatsoever and looks like a particularly tatty corner of Battersea Park (without even the hope of a glimpse of the power station's dramatic silhouette in the background)?

That's the main reason I always enjoyed going to the Globe in London. To listen to the words of Shakespeare. Which is why I object to the current season's productions - here is an excerpt from this year's Troilus and Cressida at the Globe Theatre, to demonstrate what is being lost:

Here is the full excerpt from Radio 3, with the reviewers flailing as they try to answer that question and justify their right-on, emperor's new clothes excitement about the whole sorry project:

Monday, 21 May 2012

Serving Wenches

Many years ago, when we first moved into our area, there was an establishment called Northside Health Studios operating up at our local shops. Northside Health Studios was reputed to actually be a brothel and so, when a person, not unlike these three from the wonderful Australia You're Standing in It:

lurched out of a taxi and hollered, 'Excuse me love, do you know where the health studio is?", I thought I'd teach him a lesson. 'Do you mean the brothel?' I asked, adopting my most haughty demeanour. 'Yeah, that's right,' the bloke replied, without a trace of shame. I pointed the place out and he disappeared up its staircase into realms of, presumably, bliss.

Anyway, Northside Health Studios has long since closed its doors, but lately a new, (and, I had thought, very different), enterprise has begun trading in its old location. I hadn't taken much notice of it until this morning, when I was surprised to see a rather burly man emerge from the entrance and place one of those folding advertising boards out on the pavement. The reason I was surprised is that the new place looks very touchy-feely and I'd imagined somehow it would be staffed by women. But when I looked at the star attraction, topping the list of services available, I had to concede that some things can't be provided without at least a man or two:

lurched out of a taxi and hollered, 'Excuse me love, do you know where the health studio is?", I thought I'd teach him a lesson. 'Do you mean the brothel?' I asked, adopting my most haughty demeanour. 'Yeah, that's right,' the bloke replied, without a trace of shame. I pointed the place out and he disappeared up its staircase into realms of, presumably, bliss.

Anyway, Northside Health Studios has long since closed its doors, but lately a new, (and, I had thought, very different), enterprise has begun trading in its old location. I hadn't taken much notice of it until this morning, when I was surprised to see a rather burly man emerge from the entrance and place one of those folding advertising boards out on the pavement. The reason I was surprised is that the new place looks very touchy-feely and I'd imagined somehow it would be staffed by women. But when I looked at the star attraction, topping the list of services available, I had to concede that some things can't be provided without at least a man or two:

Sunday, 20 May 2012

Mein Vater, Mein Vater

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau has died. He was wonderful. The story of his early life is a reminder that Germans, as well as other nationalities, suffered under the Nazis;

Saturday, 19 May 2012

Trees Died for This

One of the more poignantly amusing sights I've ever seen was a toddler climbing onto one of the benches in our local park and trying to take a bite out of one of its slats, recently repainted a glossy dark brown. As his gums closed on the thing's unyielding texture, his face crumpled in disappointment. 'Choc', he lisped, looking around with a puzzled air. 'He's just discovered chocolate,' I heard his mother explain to her companion, almost unnecessarily. 'Choc', the child repeated, wistfully, 'choc, choc.'

That was some time ago. Things have changed since then and I fear such simple pleasures may not be enough for the children of more recent generations - not if what some young parents told me at dinner last night is true.

These parents have a two-year-old and they also have an I-Pad. Apparently, the I-Pad is the apple of the two-year-old's eye (apple, I-Pad, geddit? Actually, it was unintentional, so don't grind your teeth at me like that). When he wakes from an afternoon nap, his first - indeed, his only - word is 'I-Pad'. He utters it in a coaxing, hopeful, go-on-please-indulge-me kind of tone. 'I-Pad?' he says, 'I-Pad?' And when he's allowed it, he can zoom straight to YouTube. 'Apparently, that means he's actually reading - he can recognise the YouTube logo, and that means he can read it,' the proud father assured me.

The child's mother seemed more ambivalent. According to her, her little son found a magazine in the kitchen yesterday. Rather than leafing through it, he tried to use the action you use on an I-Pad to move on to the next screen and looked up at her with wide eyes when the thing didn't behave as he expected. He was clearly concerned that the I-Pad was broken. The concept of a paper page was beyond his ken.

All this suggests to me that we're headed for a paperless future, which should please the hippies a friend of mine used to share a house with, who tossed away her box of teabags once in outrage, preserving a single specimen from the 80-odd the box contained. This they sellotaped above the sink, together with a post-it note, on which they'd scrawled an arrow pointing at the offending item, together with the furious message: 'Trees died for this!'

That was some time ago. Things have changed since then and I fear such simple pleasures may not be enough for the children of more recent generations - not if what some young parents told me at dinner last night is true.

These parents have a two-year-old and they also have an I-Pad. Apparently, the I-Pad is the apple of the two-year-old's eye (apple, I-Pad, geddit? Actually, it was unintentional, so don't grind your teeth at me like that). When he wakes from an afternoon nap, his first - indeed, his only - word is 'I-Pad'. He utters it in a coaxing, hopeful, go-on-please-indulge-me kind of tone. 'I-Pad?' he says, 'I-Pad?' And when he's allowed it, he can zoom straight to YouTube. 'Apparently, that means he's actually reading - he can recognise the YouTube logo, and that means he can read it,' the proud father assured me.

The child's mother seemed more ambivalent. According to her, her little son found a magazine in the kitchen yesterday. Rather than leafing through it, he tried to use the action you use on an I-Pad to move on to the next screen and looked up at her with wide eyes when the thing didn't behave as he expected. He was clearly concerned that the I-Pad was broken. The concept of a paper page was beyond his ken.

All this suggests to me that we're headed for a paperless future, which should please the hippies a friend of mine used to share a house with, who tossed away her box of teabags once in outrage, preserving a single specimen from the 80-odd the box contained. This they sellotaped above the sink, together with a post-it note, on which they'd scrawled an arrow pointing at the offending item, together with the furious message: 'Trees died for this!'

Thursday, 17 May 2012

Canberra and Velasquez

Overnight, a tree dropped all its leaves in Ainslie:

Or almost all - there's a couple of recalcitrants in every crowd (usually I'm among them, to be honest):

It was a striking sight and, as I looked at the bright carpet, I remembered being in the Metropolitan Museum in New York a month or two ago:

looking at a painting of some poor benighted infanta (Maria Theresa, actually, who didn't have, all things considered, too bad a time of it - only having to marry a first cousin, for instance, rather than an uncle):

whose 'butterfly ribbons' mirrored, it seemed to me, the shape of the fallen leaves in Ainslie:

Or almost all - there's a couple of recalcitrants in every crowd (usually I'm among them, to be honest):

It was a striking sight and, as I looked at the bright carpet, I remembered being in the Metropolitan Museum in New York a month or two ago:

looking at a painting of some poor benighted infanta (Maria Theresa, actually, who didn't have, all things considered, too bad a time of it - only having to marry a first cousin, for instance, rather than an uncle):

whose 'butterfly ribbons' mirrored, it seemed to me, the shape of the fallen leaves in Ainslie:

Monday, 14 May 2012

There But

For some time I have been haunted by a detail in an article about Rwanda that appeared in the New Yorker several years ago. It hints at aspects of the human soul I would prefer not to acknowledge. It is this comment by one of the people who took part in the massacre of Tutsi:

"For me, it became a pleasure to kill. The first time, it's to please the government. After that, I developed a taste for it. I hunted and caught and killed with real enthusiasm. It was work, but work that I enjoyed. It wasn't like working for the goverment. It was like doing your own true job - like working for myself ... I was very, very excited when I killed. I remember each killing. Yes, I woke every morning excited to go into the bush. It was the hunt."

I wouldn't mind so much, if I thought this was an isolated reaction, but what worries me is that the same potential is hidden deep inside every civilised soul, waiting for the right set of circumstances to animate it. I suppose that is what William Golding was trying to reveal in Lord of the Flies, but it is a very uncomfortable possibility to contemplate..

"For me, it became a pleasure to kill. The first time, it's to please the government. After that, I developed a taste for it. I hunted and caught and killed with real enthusiasm. It was work, but work that I enjoyed. It wasn't like working for the goverment. It was like doing your own true job - like working for myself ... I was very, very excited when I killed. I remember each killing. Yes, I woke every morning excited to go into the bush. It was the hunt."

I wouldn't mind so much, if I thought this was an isolated reaction, but what worries me is that the same potential is hidden deep inside every civilised soul, waiting for the right set of circumstances to animate it. I suppose that is what William Golding was trying to reveal in Lord of the Flies, but it is a very uncomfortable possibility to contemplate..

Sunday, 13 May 2012

Nuance

Looking at the statistics that detail health outcomes and work participation and other kinds of benchmarks as they apply to the Indigenous population of Australia, it is easy to draw the conclusion that this is a nation jam packed with thoughtless racists. However, if you set aside the usual percentage of ignorant bigots, that is actually far from the case. The relationship between the bulk of the population and the original inhabitants of this country is complex, but the goodwill that is felt by most Australians towards Aborigines is real and deeply felt. It is possibly best exemplified by the reaction of most of us to Cathy Freeman's win at the Sydney Olympics, an event that even now I can't think about without getting a lump in my throat:

Peculiarly, it was a visit to a rural supply shop the other day that set me pondering these things. Because my mum's not been well, I've been helping her out a bit and this week she needed some salt for her cattle. As I didn't know what I was doing really, I asked a man at the shop for help. He soon found a heap of what mum wanted - bags labelled Himalayan rock salt, sold in 25 kilogramme lumps.

After checking that the bags contained decent-sized single lumps and not a whole lot of 5 kilogramme pebbles, the bloke heaved several of the best onto a trolley, which he pushed out to my car. As he hefted a couple of the sacks into the boot, I noticed that there was an address printed on the side of them. It proved that they really were from the Himalayas; they were not, as I had imagined called 'Himalayan' purely from whimsy or to create a romantic impression, (and, indeed, now I come to think of it, I realise trying to endow cow salt with romance would be an unlikely marketing ploy).

Anyway, I was so surprised that I made a comment. 'They really are Himalayan', I said. The bloke from the shop dumped the second bag into the back of the car and straightened up before turning for the next one. 'Yeah', he said, pushing back his hat and wiping his forehead. 'I suppose there's some poor little bugger up there on the top of Mount Everest, pick, pick, picking away.' He bent over and grabbed hold of the corners of the next bag. 'It'd be a long hard way down with 25 kilo', he grunted, as he hurled it after the others.

After checking that the bags contained decent-sized single lumps and not a whole lot of 5 kilogramme pebbles, the bloke heaved several of the best onto a trolley, which he pushed out to my car. As he hefted a couple of the sacks into the boot, I noticed that there was an address printed on the side of them. It proved that they really were from the Himalayas; they were not, as I had imagined called 'Himalayan' purely from whimsy or to create a romantic impression, (and, indeed, now I come to think of it, I realise trying to endow cow salt with romance would be an unlikely marketing ploy).

Anyway, I was so surprised that I made a comment. 'They really are Himalayan', I said. The bloke from the shop dumped the second bag into the back of the car and straightened up before turning for the next one. 'Yeah', he said, pushing back his hat and wiping his forehead. 'I suppose there's some poor little bugger up there on the top of Mount Everest, pick, pick, picking away.' He bent over and grabbed hold of the corners of the next bag. 'It'd be a long hard way down with 25 kilo', he grunted, as he hurled it after the others.

It seemed to me that in that comment

you got all the nuance of Australian attitudes towards people less fortunate than ourselves. The phrase 'poor little bugger' encompassed an affectionate if somewhat Olympian sympathy. The man recognised the salt miner in the Himalayas might be having a tough a time of it and he also recognised that that wasn't really fair. All the same, there was in his words an implied acceptance that, looked at practically, that was how things were. Just because he didn't have any ideas about how to improve that situation, it didn't mean he didn't recognise it was far from ideal.

In the same way, our governments - state and federal - willingly hurl money at the disaster that is Indigenous education and welfare, and we are happy that they keep on doing so, because we are all aware that the situation is dire. None of us wants people to feel driven to extremes such as petrol-sniffing, but equally none of us has a clue about how to solve the myriad problems that lead to such activities. Thus, while we may appear to be uncaring, really we just don't have a clue about what to do.

In the same way, our governments - state and federal - willingly hurl money at the disaster that is Indigenous education and welfare, and we are happy that they keep on doing so, because we are all aware that the situation is dire. None of us wants people to feel driven to extremes such as petrol-sniffing, but equally none of us has a clue about how to solve the myriad problems that lead to such activities. Thus, while we may appear to be uncaring, really we just don't have a clue about what to do.

Friday, 11 May 2012

Luxury

I don't listen to the BBC's Desert Island Discs much, mainly because, in a rather aunt of Woody Allen, ('This restaurant is so bad', 'Yes and the servings are so small') ,contrary manner, I'm not very interested in music and I hate the way on the programme they don't play the chosen pieces right to the end.

The thing about the programme that I do find appealing though is finding out what luxury each desert islander chooses to take with them. Nicholas Parsons, I remember, tried, very sensibly - but unsuccessfully - for an unlimited supply of fresh water. Boris Johnson, on the other hand, demanded a huge pot of Dijon mustard, which he seemed to think would hide the taste of any nasty food he found to eat.

A bed I suppose would probably be the most useful of all items, but when I try to imagine what I'd choose I discover a streak of frivolity always getting the upper hand. Sometimes I think an endless supply of crisps would be perfect or never-ending plates of toasted cheese; at other times, I prefer the idea of an inexhaustible bottle of a scent called Caleche, or this soap, which would not only remind me of comfortable houses but give me hours of pleasure (pleasure?), thinking about the British royal family washing themselves:

; usually I return to my mainstay though, which is the self-portrait of van Eyck that they have in the National Gallery in London. I have the impression that I could look at that forever - I certainly never get sick of visiting it, but as I write this I begin to wonder whether living with it might actually be too much of a good thing. A question I will possibly never know the answer to in this case is: would familiarity eventually breed contempt?

And speaking of contempt, even though I seem to spend more of my time than is sensible engaged in housework, it has never crossed my mind to select a vacuum cleaner or a steam iron or anything to do with cooking as my luxury, (not, of course, that anyone has actually ever asked me either - but I like to be prepared). I realise too that a really comfortable pair of shoes would probably be terrifically handy, but I'm banking on the possibility that I'll be wearing those already, when I arrive.

When the chips are down, (or the toasted cheese and scented van Eyck portraits), I recognise in the end what would really be the best thing to take of all - a horse, because horses are a) such nice personalities, (on the whole - it would be bad luck if one got a mean one), b) useful for gardening and c) we could canter about from place to place, if the island turned out to be big.

What would other people choose? I'm sure there are much more exciting things I should be packing that I haven't even thought of. Ooh and look, how riveting - here's a comprehensive list of everything anyone who has ever actually been on the programme has decided they couldn't live without.

The thing about the programme that I do find appealing though is finding out what luxury each desert islander chooses to take with them. Nicholas Parsons, I remember, tried, very sensibly - but unsuccessfully - for an unlimited supply of fresh water. Boris Johnson, on the other hand, demanded a huge pot of Dijon mustard, which he seemed to think would hide the taste of any nasty food he found to eat.

A bed I suppose would probably be the most useful of all items, but when I try to imagine what I'd choose I discover a streak of frivolity always getting the upper hand. Sometimes I think an endless supply of crisps would be perfect or never-ending plates of toasted cheese; at other times, I prefer the idea of an inexhaustible bottle of a scent called Caleche, or this soap, which would not only remind me of comfortable houses but give me hours of pleasure (pleasure?), thinking about the British royal family washing themselves:

; usually I return to my mainstay though, which is the self-portrait of van Eyck that they have in the National Gallery in London. I have the impression that I could look at that forever - I certainly never get sick of visiting it, but as I write this I begin to wonder whether living with it might actually be too much of a good thing. A question I will possibly never know the answer to in this case is: would familiarity eventually breed contempt?

And speaking of contempt, even though I seem to spend more of my time than is sensible engaged in housework, it has never crossed my mind to select a vacuum cleaner or a steam iron or anything to do with cooking as my luxury, (not, of course, that anyone has actually ever asked me either - but I like to be prepared). I realise too that a really comfortable pair of shoes would probably be terrifically handy, but I'm banking on the possibility that I'll be wearing those already, when I arrive.

When the chips are down, (or the toasted cheese and scented van Eyck portraits), I recognise in the end what would really be the best thing to take of all - a horse, because horses are a) such nice personalities, (on the whole - it would be bad luck if one got a mean one), b) useful for gardening and c) we could canter about from place to place, if the island turned out to be big.

What would other people choose? I'm sure there are much more exciting things I should be packing that I haven't even thought of. Ooh and look, how riveting - here's a comprehensive list of everything anyone who has ever actually been on the programme has decided they couldn't live without.

Thursday, 10 May 2012

Confessions of a Visual Illiterate - Two for the Price of One

When I lived in Vienna, I used to go and gawp at the big Brueghel canvases they have there. Like Michael Frayn, I always thought a novel could be made from imagining how on earth one in the seasons series could possibly have been lost. Unlike Michael Frayn, I never did anything about it.

Anyway, I hadn't absorbed the fact that the painting in the series that depicts summer is part of the collection at New York's Metropolitan Museum. And so it came as a wonderful surprise to walk into one of the rooms in the museum and see the painting:

I have to say one of the things I admire about the picture is what good value for money it offers. If I'd commissioned it, I'd have been thrilled, for there are dozens of pictures within this one frame - it's not a case of two for the price of one, but several, which I suppose makes Brueghel an early precursor of Tesco's or Walmart on some level, (although no, not really)

There is the picture of village life with games being played on the green:

There is the landscape with travellers trudging down its deep lanes:

There are three scenes of harvesters at work in seas of ripe grain:

There is an orchard, complete with apple picker:

There is a distant coastal town, with the faint outlines of ships, hinting at possibilities over the horizon:

There is another peaceful glimpse of village life:

And there is me, all those years ago, stuffing my face, as ever:

Anyway, I hadn't absorbed the fact that the painting in the series that depicts summer is part of the collection at New York's Metropolitan Museum. And so it came as a wonderful surprise to walk into one of the rooms in the museum and see the painting:

I have to say one of the things I admire about the picture is what good value for money it offers. If I'd commissioned it, I'd have been thrilled, for there are dozens of pictures within this one frame - it's not a case of two for the price of one, but several, which I suppose makes Brueghel an early precursor of Tesco's or Walmart on some level, (although no, not really)

There is the picture of village life with games being played on the green:

There is the landscape with travellers trudging down its deep lanes:

There is an orchard, complete with apple picker:

There is a distant coastal town, with the faint outlines of ships, hinting at possibilities over the horizon:

There is another peaceful glimpse of village life:

Wednesday, 9 May 2012

Battered Penguins - South Wind by Norman Douglas

I read some advice to writers given by Martin Amis the other day, to this effect: when reading, you should ask yourself constantly, 'How are they doing this, how are they creating this effect, how have they set up this scene, how have they created this character'. I thought I'd give it a go when reading South Wind. Very quickly though, I found myself drifting from 'How?', to 'Why?'

As page after page of tangled description and meandering plot line, (if this flimsy bit of gossamer could be given such a substantial description), confronted me, I became less and less able to understand what the hell Norman Douglas was thinking of as he wrote this heap of pages that he eventually called a novel.

A character is introduced, you follow him for a bit, and then another is introduced, and you are led off with him for a while. Another appears, and you wander off in the direction he takes for a few pages, before being introduced to someone else, who goes somewhere else and does something else, without any real connection or reference to those other characters you have already met. This goes on for hundreds of pages. As each new figure appears, you, the reader, like a starving man in the desert, clutch at them more desperately, hoping that at last you have found a central figure to cling to, a hero whose story will enlighten everything, a hero who will actually have a story, one that moves from somewhere to somewhere, one that will possibly even reach some kind of dramatic conclusion.

I used to think the phrase 'narrative arc' was an annoying publishing cliche, but now that I have read South Wind I am not so sure.

I should point out that there are amusing moments in South Wind and interesting apercus, but in the end the book is too much like Nepenthe itself, the book's setting, (a thinly disguised Capri, apparently), about which one character remarks, 'The canvas of Nepenthe is rather over-charged'.

Douglas may possibly have intended the book as some kind of fairy tale. Certainly, the fairy tale is a motif that recurs a couple of times - and the book actually ends with mention of one. There is one exciting moment, after hundreds of pages of rambling, when Douglas appears to have finally settled on murder-mystery as his form, but he rapidly lets the idea fall. Could the thing be a meditation on England - the island in the book is its antithesis and the text contains many observatons about being English? In the end, I have to admit that I have no idea.

To sum up, I am baffled by this book, with its crowd of well-observed characters having wordy and sometimes witty conversations. DH Lawrence portrayed Norman Douglas as Argyle in Aaron's Rod, (they fell out badly as a result); quite frankly, even a novel by DH Lawrence, for all his foibles and flaws, supplies more satisfaction for a reader, in my view, than does South Wind. And yet the book is not, paragraph by paragraph, badly written, and I know of readers who regard it as a brilliant work of early modernism. Therefore, I hesitate to condemn it. It is not undiverting; it is merely hard to get hold of or quite see the point of.

I'm haunted by the suspicion that it is simply a lack of sophistication that stands as a barrier between me and admiration of this novel. The same unsophistication means that I am appalled by another work of Douglas's, an absolutely filthy collection of limericks that he gathered and annotated. If you are at all easily shocked, I should leave them well alone, but perhaps somewhere within this latter work there may be some clue as to what the hell he was up to when he was writing South Wind.

Tuesday, 8 May 2012

Wish You Were Here

Sold on the line that the new Australian film Wish You Were Here was this year's Animal Kingdom, we went along to the cinema to see it on Saturday night. While neither film presents a flattering picture of contemporary Australians, Wish You Were Here, disappointingly, was never in Animal Kingdom's league.

Which is not to say it wasn't worth seeing. The film is never boring. Its portrayal of Australians treating Asia as their playground, a place to abandon normal standards of behaviour and spend as much time as possible completely ripped, is probably all too accurate. However, it didn't make the main characters particularly sympathetic. Additionally, I found the plot pretty unbelievable in a number of places. This may merely indicate that I lead a sheltered life, but it seemed unlikely to me that a couple - one member of whom was pregnant - would abandon their two small children for a week in order to head off to Cambodia for a holiday with a young relative and her boyfriend, who they had barely met. Once there, I was pretty surprised that the pregnant wife seemed unperturbed when her husband decides to indulge in a few recreational drugs. On their return to Sydney, I was even more astonished by some of the decisions taken by the pregnant wife, decisions that I suspected a male scriptwriter might believe in but that most women who have been pregnant would view as fairly unlikely - my sense is that, no matter what your own emotional turmoil may be, when pregnant you never ignore the safety of your unborn child.

The film is well-acted and beautifully shot and it provides a pretty damning indictment of a kind of thoughtless, ignorant hedonism that may be all too prevalent in Sydney - it will certainly confirm everything my Victorian relatives think about Sydneysiders. The trouble is I'm not sure the story of a bunch of extremely shallow people (and, if you don't think they're shallow, how do you explain their equanimity in the face of Gracie's unscheduled appearance, which, after delivering a momentary emotional jolt, appears to leave their lives quite unruffled) really amounts to anything, especially as the ending just dribbles out.

Which is not to say it wasn't worth seeing. The film is never boring. Its portrayal of Australians treating Asia as their playground, a place to abandon normal standards of behaviour and spend as much time as possible completely ripped, is probably all too accurate. However, it didn't make the main characters particularly sympathetic. Additionally, I found the plot pretty unbelievable in a number of places. This may merely indicate that I lead a sheltered life, but it seemed unlikely to me that a couple - one member of whom was pregnant - would abandon their two small children for a week in order to head off to Cambodia for a holiday with a young relative and her boyfriend, who they had barely met. Once there, I was pretty surprised that the pregnant wife seemed unperturbed when her husband decides to indulge in a few recreational drugs. On their return to Sydney, I was even more astonished by some of the decisions taken by the pregnant wife, decisions that I suspected a male scriptwriter might believe in but that most women who have been pregnant would view as fairly unlikely - my sense is that, no matter what your own emotional turmoil may be, when pregnant you never ignore the safety of your unborn child.

The film is well-acted and beautifully shot and it provides a pretty damning indictment of a kind of thoughtless, ignorant hedonism that may be all too prevalent in Sydney - it will certainly confirm everything my Victorian relatives think about Sydneysiders. The trouble is I'm not sure the story of a bunch of extremely shallow people (and, if you don't think they're shallow, how do you explain their equanimity in the face of Gracie's unscheduled appearance, which, after delivering a momentary emotional jolt, appears to leave their lives quite unruffled) really amounts to anything, especially as the ending just dribbles out.

Monday, 7 May 2012

I Take it Back

We lived in London for four years and about halfway through our time there we came back to Australia for a few weeks. When we got to Sydney, we realised we'd both completely forgotten our bank account pin numbers. The next morning, with heavy heart, we set off down Crown Street, Surry Hills to try to persuade the bank to supply us with new ones. Imagine our surprise when we walked through the door and were greeted by a smiling young woman who provided us with new numbers without fuss or complication. We gave her a few bits of information, she cheerily sorted things out for us and we went on our way.

So I shouldn't be mean about the Commonwealth Bank for a single millisecond. They are so much better than the British banks we dealt with, where our experiences mirrored pretty closely those recounted by a man called Parsons on the BBC's Now Show the other day:

So I shouldn't be mean about the Commonwealth Bank for a single millisecond. They are so much better than the British banks we dealt with, where our experiences mirrored pretty closely those recounted by a man called Parsons on the BBC's Now Show the other day:

Saturday, 5 May 2012

More Good Design

It was such a pleasure to see in Euroa that the bank I keep - in as much as 'keep' is the right verb - my money with made the sensible decision to knock down this horrid fusty old building:

in order to put this one up instead:

Presumably they display the evidence in their window because of the pride they feel about what they've done. At the Commonwealth Bank, they have clearly been visionaries since way back (well, the sixties anyway). That would be why they decided to go with that nice yellow and black combination for their corporate colours. It's so smart and attractive, isn't it? I haven't yet managed to get a job with the Commonwealth so I can't wear their uniform, but I do try to wear yellow and black as much as possible in my private life. The yellow complements the whites of my eyes so perfectly and the black complements the dirt under my fingernails. They call it colour coordination in fashion circles, I believe.

in order to put this one up instead:

Presumably they display the evidence in their window because of the pride they feel about what they've done. At the Commonwealth Bank, they have clearly been visionaries since way back (well, the sixties anyway). That would be why they decided to go with that nice yellow and black combination for their corporate colours. It's so smart and attractive, isn't it? I haven't yet managed to get a job with the Commonwealth so I can't wear their uniform, but I do try to wear yellow and black as much as possible in my private life. The yellow complements the whites of my eyes so perfectly and the black complements the dirt under my fingernails. They call it colour coordination in fashion circles, I believe.

Friday, 4 May 2012

A Curious Obsession

While travelling recently, I realised something that I had up until then only been unconsciously aware of - designers have a peculiar fascination with taps, (especially those associated with showers.) In the places I stayed, I encountered taps that reminded me of something a ship's captain might use on the poopdeck (is that the right word and should it be used in a bathroom context?)

plus brass objects that appeared to be misplaced sundials, chrome gearsticks and odd steel swan-neck type arrangements that had to be manipulated out at an odd angle from the wall. I never got the hang of any of them and, as a result, most mornings ended up with either blasts of cold water straight in my face when I least expected it or utterly soaked bathroom floors and ceilings.

Why do they do it? Why fiddle with the functional? Why not invent a tomato sauce bottle that works without effort instead, (and, no, I don't think those horrible little sachet things you pinch open so that they can spray all over you are a good solution)? After all, if the considerable energy and ingenuity that have been put into redesigning the tap - an object that worked perfectly well to begin with - had been redirected to solving world poverty, (say), there would be more than one good consequence. As well as allowing all of us to set out on our travels without the lurking worry that we may not get a single decent shower until we get home again, it would remove Bono entirely from our lives, (oh yes, and it would relieve the suffering of countless millions, which would be quite good as well).

plus brass objects that appeared to be misplaced sundials, chrome gearsticks and odd steel swan-neck type arrangements that had to be manipulated out at an odd angle from the wall. I never got the hang of any of them and, as a result, most mornings ended up with either blasts of cold water straight in my face when I least expected it or utterly soaked bathroom floors and ceilings.

Why do they do it? Why fiddle with the functional? Why not invent a tomato sauce bottle that works without effort instead, (and, no, I don't think those horrible little sachet things you pinch open so that they can spray all over you are a good solution)? After all, if the considerable energy and ingenuity that have been put into redesigning the tap - an object that worked perfectly well to begin with - had been redirected to solving world poverty, (say), there would be more than one good consequence. As well as allowing all of us to set out on our travels without the lurking worry that we may not get a single decent shower until we get home again, it would remove Bono entirely from our lives, (oh yes, and it would relieve the suffering of countless millions, which would be quite good as well).

Tuesday, 1 May 2012

Beneath Western Skies

I was admiring the quiet Islington streets near where my sister-in-law lives when my daughter pointed out that there was a teeming sky-highway above our heads:

Words and Phrases that Annoy Me

I've been under a bit of stress lately, and when that happens I become pedantic, which is why, after months without this kind of post, suddenly there are two only a few days apart.

The phrase that is annoying me today is 'longer hours', as in, 'People are being asked to work longer hours', 'Longer hours are bad for your health', 'Recession means longer hours at work', et cetera. This is absurd. An hour is an hour, it can't be longer or shorter. People may be being asked to work more hours. Many hours at work may be bad for your health, but each hour remains the same, neither longer nor shorter.

There, that's off my chest - should I mention the issue of 'cheaper prices'. No, leave it alone - you don't want to look like an all-round obsessive. Or is it too late already?

The phrase that is annoying me today is 'longer hours', as in, 'People are being asked to work longer hours', 'Longer hours are bad for your health', 'Recession means longer hours at work', et cetera. This is absurd. An hour is an hour, it can't be longer or shorter. People may be being asked to work more hours. Many hours at work may be bad for your health, but each hour remains the same, neither longer nor shorter.

There, that's off my chest - should I mention the issue of 'cheaper prices'. No, leave it alone - you don't want to look like an all-round obsessive. Or is it too late already?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)