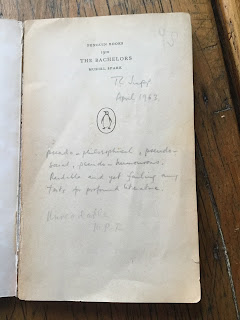

I have several secondhand Muriel Spark books, and as I make my way through them I feel persistently confused. I cannot dismiss her, but I don't always enjoy her. In the case of The Bachelors my problems began when I read what a couple of earlier owners wrote on the frontispiece of my copy:

T.L. Jupp's judgment having read the book in April, 1963 was as follows:

'Pseudo-philosophical, pseudo-social, pseudo-humourous. Readable and yet failing any tests for profound literature.'

Someone identifying themselves only as M. P-R added a one-word verdict:

'Unreadable.'

These comments prejudiced me as I approached the opening page and echoed in my mind as I progressed through the novel.

The truth is that the book isn't unreadable; all the same, it doesn't make you grab it off the bedside table, excited at the prospect of ploughing on. I think at least for those who are unreceptive or a bit resistant, as I was, it is a book that needs a second reading (Note No. 1), It is only in looking back over it that I have begun dimly to discern something strange and haunting in the book. I can't quite make it out, but it is definitely intriguing - although possibly not so intriguing that I will leap back to reading it again soon, or probably ever, to be quite honest.

The central difficulty that I have is that Spark doesn't give the impression that she cares about making her readers happy or comfortable, but she does give the impression that she quite likes showing off. She starts from a position of contempt for humanity. If she includes herself in her contempt, she to some extent gives herself a pass for being intelligent enough to recognise everybody else's despicable self-delusion. She may be right to consider herself god-like in her lack of illusion about humanity, but she lacks the Christian god's supposed affection for our species. The fact that she despises everyone is understandable but not terrifically enjoyable.

The book opens with a chance meeting between two acquaintances. One is Ronald Bridges, a 37-year-old curator who at 23 started to have epileptic fits and who, as a result, was unable to become a priest and feels that he is possessed by a demon and yet at times feels he has become 'a truth-machine, under which his friends took on the aspect of demon-hypocrites'. At one point later in the text, we see him overcome by such 'melancholy and boredom' that he must recite 'to himself as an exercise against it, a passage from the Epistle to the Philippians, which was at present meaningless to his numb mind, in the sense that a coat of paint is meaningless to a window-frame, and yet both colours and preserves it' After coming home from a party, he uses this passage, when, in retrospect the 'party stormed upon him like a play in which the actors had begun to jump off the stage, so that he was no longer simply the witness of a comfortable satire, but was suddenly surrounded by a company of ridiulous demons' Philippians is to him 'a mere charm to ward off the disgust, despair, and brain-burning.'

The person Ronald runs into is Martin, a barrister of 35 who has a rather pallid relationship with someone called Isabel - Spark is brilliant at describing his ambivalence about her, (Note No. 2). Martin lives with his mother and an old nurse called Carrie who is now his mother's housekeeper. Spark's shrewdness is brilliantly in evidence in her description of Martin's dealings with these two women:

'He tried to entertain them and to be a good son', she explains, 'They bored him, but when they went away from home he missed the boredom and the feud between them which sometimes broke into it'

Martin's mother tells him that Carrie, his former nurse, should go into a home, but he insists she remain with them.

'"You're after that money of hers...", his mother said. He hated her fiercely for her continual robbing him of any better motive. "I'm fond of Carrie," he said. But now his mother had left him wondering if he really meant it.'

Spark has caught the subtle way in which a parent can undermine an adult child.

Ronald and Martin talk about the price of frozen peas and shopping in general, until they spot 'a small narrow-built man...thin, with a very pointed, anxious face and nose, and a grey-white lined skin. He would be about fifty-five. He wore a dark blue suit.' This is Patrick Seton, who Martin will soon be prosecuting in the magistrates' court for fraud.

Patrick Seton is a wonderfully creepy character. He is devastatingly amoral - Spark explains, writing about someone's correct suspicion that Patrick intends to kill someone, 'If you could call it an intention, when a man could wander into a crime as if blown like a winged leaf.'

The plot involves séances and a Catholic priest called Father Socket, who says, among other things, 'There is nothing like having a card index in the house. You can always produce a card index. It puts them off their stroke', a gay man called Mike, to whom 'Father Socket cited the classics and André Gide, and although Mike did not actually read them he understood, for the first time in his life that the world contained scriptures to support his homosexuality which, till now had been shifty and creedless.'

As in Graham Greene's The Human Factor the only truly decent figure (Note No. 3) in The Bachelors is a person without guile or subtlety. Her name is Elsie Forrest, a young woman who begins as a devotee of Father Socket - 'To Elsie it was a labour of love typing out his papers on the subjects of the Cabbala, Theosophy, Witchcraft, Spiritualism, and Bacon wrote Shakespeare, besides many other topics', (such a wonderful charlatan's list) - but is shocked out of her hero worship. She has a rather Beckettian tone when she observes of Seton, 'I always said he wasn't much of a man to look at. Thin about the thighs. You can't disguise it', but my favourite Elsie line is the profound yet banal: 'I think it's better to be born. At least you know where you are.'

The book is haunted by faith, whether the faith of the women Patrick seduces, (which is sometimes more fear than anything, just as religious faith can be), the faith of those who attend séances, and the faith of Ronald, who is Catholic. When Spark describes how Ronald is used to hearing over the years from hostesses at the social events he attends the statement 'I'm anti-Catholic' and has 'devised various ways of coping with it, according to his mood and to his idea of the Hostess's intentions', I suspect she is really relating a piece of her own experience. In any case, the passage provides some amusing ways to counter those who do challenge one's faith:

'If the intelligence seemed to be high and Ronald was in a suitable mood, he replied, "I'm anti-Protestant" - which he was not, but it sometimes served to shock them into a sense of their indiscretion. On one occasion where the woman was a real bitch, he had walked out. Sometimes he said, "Oh, are you? How peculiar." Sometimes he allowed that the woman was merely trying to start up a religious argument and he would then attempt to explain where he stood with his religion. Or again he might say, "Then you've received Catholic instruction?" and, on hearing that this was not so, would comment, "Then how can you be anti- something that you don't know about?" which annoyed them; so that Ronald felt uncharitable.'

Later, Ronald tells another character, 'As a Catholic I loathe all other Catholics', which made me laugh out loud. In that scene he goes on to say: 'Don't ask me .. how I feel about things as a Catholic. To me, being Catholic is part of my human existence. I don't feel one way as a human being and another as a Catholic.' I think many Catholics would understand that well.

Although I have not fully understand how, it is fairly clear that Ronald is the lynchpin of the book. It is he who accompanies us through the final paragraphs in which, as elsewhere, if he is not exactly a godlike figure, he is at least the closest person in the book to the supernatural elements of the deity:

'Ronald went home to bed. He slept heavily and woke at midnight, and went out to walk off his demons.

Martin Bowles, Patrick Seton, Socket.

And the others as well, rousing him up: fruitless souls, crumbling tinder, like his own self which did not bear thinking of. But it is all demonology, he thought, and he brought them all to witness, in his old style, one by one before the courts of his mind...He sent these figures away like demons of the air until he could think of them again with indifference or amusement or wonder ... It is all demonology and to do with the creatures of the air, and there are others besides ourselves, he thought, who lie in their beds like happy countries that have no history. Others ferment in prison; some rot, maimed; some lean over the banisters of presbyteries to see if anyone is going to answer the telephone.

He walked round the houses, calculating, to test his memory, the numbers of the bachelors - thirty-eight thousand five hundred streets, and seventeen point one bachelors to a street - lying awake, twisting and murmuring, or agitated with their bedfellows, or breathing in deep repose between their sheets, all over London, the metropolitan city.'

In this overview, with its remote gaze giving a perspective on humanity as a whole rather than as individuals, there is something strange, although I am ashamed to say I cannot quite understand what exactly. But perhaps it is mystery itself that we are being directed to notice, and it is mystery after all that lies at the heart of existence.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note No. 1: When forced to write essays on things that I'd read, I used to wonder how the activity was justifiable; I couldn't see how it benefited anyone. Finally, I realised that the main purpose of writing about a work of literature is to force oneself to examine what one has read in a thoughtful way. Nostromo by Joseph Conrad was the book that made me understand this. I read it when I was sixteen and thought it was the most boring thing on earth, until I was asked to answer a question on it and had to think about it carefully and was unable to escape the recognition that it was brilliant, complex and wise.

Note No. 2 'He had poured their drinks when she returned with new make-up on her face. He had often felt the only safe course would be to marry her, and he felt this now, with fear, because she did not always attract him, and he was not sure she would accept him. At the times when she stood out for her rights, not crudely, but with all the implicit assumptions, he thought her face too fat and found her thick neck and shoulders repulsive.'

Note No. 3: Colonel Daintry

She has a good Catholic sense of everyday evil. I read it incited by your review. So many characters and locales and sub plots all transpiring in one week. Very smooth progression of events. As well as that there was the uncanny thought that Seton might also be slightly genuine as a medium. I enjoyed it and wrote a little review myself. As you say doing so sharpens one's perceptions.

ReplyDelete"a good Catholic sense of everyday evil" - I wish I had put it half so well. I have to admit that it never crossed my mind that Seton was not halfway genuine - but I assumed that that was the influence of the Enemy.

ReplyDelete