Here are some films I saw this month and what I thought about them.

I Give it a Year

This was a film about how two people of different classes somehow got together and had a big wedding and then realised they were not suited. Given that Rafe Spall is possibly the most unattractive man in cinema today it was hard to accept the basic premise that Rose Byrne would allow him to come within five yards of her in the first place - equally implausible was the idea that anyone would spend even a tiny amount of time with the character played by Stephen Marchant, let alone be such good friends with him as to invite him to be their best man. To hide the fact that the whole thing was basically about snobbery the people who Rafe Spall and Rose Byrne eventually ended up with were both cast as Americans. The concept was an age-old mismatched lovers scenario but, instead of wit or even farce, we got to see lots of pictures of Rafe Spall's penis, all of which I dearly wish I could unsee. The final shot looked like something from a Mozart opera and made me wish I'd stayed home and watched a recording of Cosi Fan' Tutte on the telly instead. Witless, graceless, vulgar, all round ghastly. Apart from what I have to concede was a mildly amusing scene at a marriage counsellor, ugh, ugh, ugh.

The Paperboy

Fun, brightly coloured and really enjoyable. Nicole Kidman brilliantly hilarious, Zac Efron almost as handsome as early James Dean (although I suppose there isn't any other kind of James Dean, now I come to think of it), Matthew MacConaghey (spelling?) v good too and Macy Grey wonderfully endearing. Underlying themes of race relations, if one wants to get serious, but really just a big vivid movie to entertain you on a Saturday night. A couple of gory scenes and a bit of fairly unsavoury sex but plenty of advance warning so you can quickly hide your eyes.

Performance/A Late Quartet

Unspeakably ponderous attempt to portray the life of a string quartet, a subject much better covered by various documentaries about real string quartets. Several (well four, mainly, funnily enough) well-known actors pretend to be musicians and, perhaps distracted by the effort of having to manipulate their unfamiliar instruments, provide uniformly wooden performances. Of course their lines don't help: oddly, given the subject matter, the entire script is completely lacking in any kind of music, (I mean verbal music as opposed to the ever-present soundtrack, which treacles its way through any crevice in the relentlessly dreary back and forth between the protagonists).

Clunk, clunk, clunk, each slab of high-minded, portentous dialogue assaults our ears with the dreadful toneless quality of the genuinely banal and, as a result, when the protagonists erupt into violent conflict and/or sudden passion, I have no idea why I'm supposed to care. The worst of them is Philip Seymour Hoffman - who runs Rafe Spall a close second for most unappetising male lead in current cinema, even if he is, as everybody insists, a marvellous actor (I'll have to take their word for it as it doesn't strike me right between the eyes). He blunders about Central Park looking unfit and palely hairy in a tracksuit, yet ends up in bed with a sultry flamenco dancer, in a development that is a) pure male fantasy and b) one of the most stomach-turning sex scenes I've seen in years, (but then the sight of Philip Seymour Hoffman with his shirt off is enough to make me queasy).

The major aspect of interest for me in the film was the furniture in Christopher Walken's apartment. Once they started smashing that, I left. If you are after a film about music, take my advice and give this one the flick; get out a DVD of Fellini's Prova d'Orchestra instead.

Tuesday, 30 April 2013

Monday, 29 April 2013

Freecycle - The Mad, The Useless and The Just Plain Terrifying

Category A, (the Mad), Exhibits a to c:

Offer - Leaves (presumably posted by A. Tree of Forrest [Canberra joke])

Offer - Stinging nettles

Offer - Chocolate cardigan

Offer - Hen with crowing problem (aka a rooster?)

Category B, (the Useless), Exhibits d to g:

Offer - Victa mower (not working)

Offer - Slow cooker (faulty)

Offer - Cracked fish tank

Offer - Fairy Wish Jar (presumably that's a jam jar to you or me)

Category C, (the Just Plain Terrifying), Exhibits h to i:

Wanted - a human skeleton

Offer - Boys' skins

Offer - Leaves (presumably posted by A. Tree of Forrest [Canberra joke])

Offer - Stinging nettles

Offer - Chocolate cardigan

Offer - Hen with crowing problem (aka a rooster?)

Category B, (the Useless), Exhibits d to g:

Offer - Victa mower (not working)

Offer - Slow cooker (faulty)

Offer - Cracked fish tank

Offer - Fairy Wish Jar (presumably that's a jam jar to you or me)

Category C, (the Just Plain Terrifying), Exhibits h to i:

Wanted - a human skeleton

Offer - Boys' skins

Sunday, 28 April 2013

Is It That Time Already

Many years ago, I set out with my seven-year-old to Vienna's Natural History Museum. As a child, I'd been taken once a week by my school to the museum's counterpart in London.

Upon arrival, we were all given hardboard clipboards and paper and pencils and dispatched to draw whatever caught our eye. I spent many of those afternoons trying unsuccessfuly to make a likeness of the stuffed dodo or, even more frustrating, attempting to capture on paper the amazing display inside the hummingbird case.

I'd been defeated every single week, unable to produce anything remotely worth bringing home. All the same the one thing I'd discovered was how trying to draw something really makes you look at it - and I found that intense observation peculiarly enjoyable. I thought my daughter might too.

She did. What was more she didn't encounter any of my difficulties. She plonked herself down in front of a stuffed albatross and came up with something alarmingly good. I'd forgotten all about it until, going through the filing cabinet, I found the drawing she made that day, stuck between some plans from the 1930s, when our house was first built.

I suppose it was probably inevitable that she'd end up pursuing a career as an illustrator but, as it's her birthday today, I thought she might like to be reminded of that long ago outing.

If anyone wishes to give her a present by buying a piece of her work, they can go to her Etsy shop, or contact her direct - or through her agent - to arrange a commission.

Happy birthday, Anna. Much love, mum.xxx

Upon arrival, we were all given hardboard clipboards and paper and pencils and dispatched to draw whatever caught our eye. I spent many of those afternoons trying unsuccessfuly to make a likeness of the stuffed dodo or, even more frustrating, attempting to capture on paper the amazing display inside the hummingbird case.

I'd been defeated every single week, unable to produce anything remotely worth bringing home. All the same the one thing I'd discovered was how trying to draw something really makes you look at it - and I found that intense observation peculiarly enjoyable. I thought my daughter might too.

She did. What was more she didn't encounter any of my difficulties. She plonked herself down in front of a stuffed albatross and came up with something alarmingly good. I'd forgotten all about it until, going through the filing cabinet, I found the drawing she made that day, stuck between some plans from the 1930s, when our house was first built.

.jpg) |

| Apologies for the fold lines |

If anyone wishes to give her a present by buying a piece of her work, they can go to her Etsy shop, or contact her direct - or through her agent - to arrange a commission.

Happy birthday, Anna. Much love, mum.xxx

Friday, 26 April 2013

Going Too Far

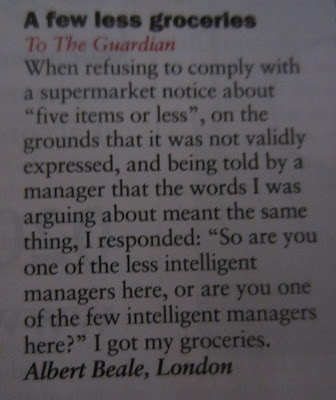

Pedantry is one thing, (a vice, some might say, from which I suffer badly). Whilst I wouldn't go that far, I would agree that boasting about it is distinctly beyond the pale:

Wednesday, 24 April 2013

Larkin Was Right

Over at

The Dabbler, I've written about Jeanette Winterson's Oranges Are

Not the Only Fruit, which I read - and loved - the other day. It's

the story of a child brought up by a madwoman. I empathised with that

child, but I realised as the story went along that, to my discomfort,

I also envied her. The reason I envied her was that she was allowed to

eat oranges. At almost all junctures in the story – moments of

happiness, moments of chaos or cataclysm or disaster –

her mother offers her oranges.

My mother

never allowed me to eat oranges. Ever. Which is probably one reason I remember the

afternoon when I was diagnosed with measles so well.

I lay on the sofa after the doctor had left. My mother, having propped me up with pillows and wrapped me in an eiderdown, went to the telephone to ring my grandmother. I was supposed to be going to stay a few days with her, but now my visit would have to be delayed. Even though I was on the other side of the room from the telephone, I clearly heard my grandmother's reaction. 'What am I going to do with all these oranges?' she shrieked down the line.

I lay on the sofa after the doctor had left. My mother, having propped me up with pillows and wrapped me in an eiderdown, went to the telephone to ring my grandmother. I was supposed to be going to stay a few days with her, but now my visit would have to be delayed. Even though I was on the other side of the room from the telephone, I clearly heard my grandmother's reaction. 'What am I going to do with all these oranges?' she shrieked down the line.

The thing

was my grandmother had bought in oranges for me, specially, knowing

that I loved them and wasn't allowed them at home. The reason I

wasn't allowed oranges was that my mother didn't much like the smell of them.

That was sufficient grounds for banning them, and no-one, least of

all me, ever dared suggest to her that this might not be reasonable (to be honest, I hardly dared think such a thing, even in the privacy and safety of my own head). But, as I read

Winterson's account of her own childhood and thought about my

mother's orange edict, it did occur to me that I might have more

in common with the book's young heroine than I had initially thought.

My mother

might not have belonged to a marginal church. She might not have been

besotted by the idea of my becoming a missionary. Nevertheless, like

Mrs Winterson she was – and remains - a pretty powerful

personality. Her most enduring legacy – besides the idea that

oranges are slightly subversive - is an indelible conviction that

having fun is not a legitimate use of time. Like Mrs Winterson,

probably like almost all parents everywhere, (possibly even all humans), my mother, although she

means well on the whole, is actually somewhat strange.

Tuesday, 23 April 2013

Sleeping Dogs

An envelope addressed to me arrived yesterday. I couldn't recognise the handwriting or the postmark and so I tore it open with curiosity. Several papers fell out, and the top one was headed 'Reunion'. It was an invitation to a tour of my old school, followed by a dinner with all my old school fellows. My initial reaction was interest. It was such a long time ago, what would they all be like, it would be so intriguing.

I unfolded the papers and read through the details. It wasn't expensive; it would be a laugh. I looked at the names of the various organisers, names of people I hadn't thought of for decades. In the back of my mind, doubts began to gather.

Was it my imagination or were the people who had taken on the dreary tasks of organising and catering not exactly the same people who'd always been desperately scuttling about trying to be accepted all those years ago? And hadn't I actually had virtually nothing in common with almost all of these people and been overjoyed at the end of each term when I could finally go home and spend some time away from them (and, in fact, during term time, hadn't I spent an unusually large number of hours inside my cupboard, with a torch and a bag of sweets, sitting on my laundry bag, reading peacefully [actually wouldn't any number of hours thus spent be classifiable as 'an unusually large number')?

Then I unfolded the 'Questionnaire', which was labelled 'Just for Fun'. As I read through the questions, memories of schooldays 'fun' came flooding back.

Of course, the thing was such a hoot, where was my sense of humour, really. It was all meant as 'a bit of a giggle', that was all. 'If you made it to university' it began, (perish the thort being the implication in that particular milieu - amazing to think one's parents paid for a school where the prevailing ethos was one of scorn for scholarship), 'did you manage to finish?' Were you to answer yes to that question then, if the values of the old days still remained in force among the group, you had instantly marked yourself down as a loser swat.

Next came, 'How many times have you been married?' which made no allowance for anyone who might have failed to get over that vital hurdle - but then again it was the main goal of a woman's life, don't you know. There followed: 'How many times have you been unfaithful?' (again, an assumption that you have at least once),'Have you got a lover now?', 'If yes, is your lover male or female' (oh the frisson of pure horrified excitement at the wild suggestion behind that one), 'What age were you when you married?' (a very important question - code for did you really win the race or just get taken off the shelf by someone who hadn't been a winner either), 'Have you lied about your children's paternity?' (I am so po-faced aren't I - I just find that such an awful idea and really unfunny as a possibility - gosh, I'm beginning to feel fifteen all over again), 'If yes, how often and how many fathers?', 'How often do you take cruises?' (what planet are these people on?), 'Do you play bridge?', 'Do you knit, crochet, do tapestry?', 'Do you take blood pressure medicine?' and on and on it nosily, (oh come on, ZMKC, it's just a giggle), goes.

Shudder, shudder, shudder, I had genuinely forgotten that these ninnies formed the background of my days for several years.

And double shudder, I had also forgotten that I, while possibly less tawdry (or more prim and dreary) in my preoccupations, had also been at fault in a much more reprehensible way. The fickleness that I cannot explain but which was a major feature of my personality in my childhood meant that I made and broke friendships utterly thoughtlessly and in a manner that makes me feel thoroughly ashamed. I realise now that I must have genuinely hurt people's feelings. How dreadful, especially at a boarding school to be left suddenly, inexplicably, high and dry by someone who you'd thought was a friend. I really was extremely horrid.

So, I won't be going to my reunion, but I'm grateful to have been invited. It was an unpleasant blast from the past that shook my complacency. I can't undo the things I did all that time ago, but I'm glad I've been reminded what a beast I was. It will spur me on to try to be better and kinder from now on. I wonder if I should start by learning bridge.

I unfolded the papers and read through the details. It wasn't expensive; it would be a laugh. I looked at the names of the various organisers, names of people I hadn't thought of for decades. In the back of my mind, doubts began to gather.

Was it my imagination or were the people who had taken on the dreary tasks of organising and catering not exactly the same people who'd always been desperately scuttling about trying to be accepted all those years ago? And hadn't I actually had virtually nothing in common with almost all of these people and been overjoyed at the end of each term when I could finally go home and spend some time away from them (and, in fact, during term time, hadn't I spent an unusually large number of hours inside my cupboard, with a torch and a bag of sweets, sitting on my laundry bag, reading peacefully [actually wouldn't any number of hours thus spent be classifiable as 'an unusually large number')?

Then I unfolded the 'Questionnaire', which was labelled 'Just for Fun'. As I read through the questions, memories of schooldays 'fun' came flooding back.

Of course, the thing was such a hoot, where was my sense of humour, really. It was all meant as 'a bit of a giggle', that was all. 'If you made it to university' it began, (perish the thort being the implication in that particular milieu - amazing to think one's parents paid for a school where the prevailing ethos was one of scorn for scholarship), 'did you manage to finish?' Were you to answer yes to that question then, if the values of the old days still remained in force among the group, you had instantly marked yourself down as a loser swat.

Next came, 'How many times have you been married?' which made no allowance for anyone who might have failed to get over that vital hurdle - but then again it was the main goal of a woman's life, don't you know. There followed: 'How many times have you been unfaithful?' (again, an assumption that you have at least once),'Have you got a lover now?', 'If yes, is your lover male or female' (oh the frisson of pure horrified excitement at the wild suggestion behind that one), 'What age were you when you married?' (a very important question - code for did you really win the race or just get taken off the shelf by someone who hadn't been a winner either), 'Have you lied about your children's paternity?' (I am so po-faced aren't I - I just find that such an awful idea and really unfunny as a possibility - gosh, I'm beginning to feel fifteen all over again), 'If yes, how often and how many fathers?', 'How often do you take cruises?' (what planet are these people on?), 'Do you play bridge?', 'Do you knit, crochet, do tapestry?', 'Do you take blood pressure medicine?' and on and on it nosily, (oh come on, ZMKC, it's just a giggle), goes.

Shudder, shudder, shudder, I had genuinely forgotten that these ninnies formed the background of my days for several years.

And double shudder, I had also forgotten that I, while possibly less tawdry (or more prim and dreary) in my preoccupations, had also been at fault in a much more reprehensible way. The fickleness that I cannot explain but which was a major feature of my personality in my childhood meant that I made and broke friendships utterly thoughtlessly and in a manner that makes me feel thoroughly ashamed. I realise now that I must have genuinely hurt people's feelings. How dreadful, especially at a boarding school to be left suddenly, inexplicably, high and dry by someone who you'd thought was a friend. I really was extremely horrid.

So, I won't be going to my reunion, but I'm grateful to have been invited. It was an unpleasant blast from the past that shook my complacency. I can't undo the things I did all that time ago, but I'm glad I've been reminded what a beast I was. It will spur me on to try to be better and kinder from now on. I wonder if I should start by learning bridge.

Sunday, 21 April 2013

Words and Phrases - a Continuing Series

I just heard a man on the radio say that the failure of the Apollo 13 mission was "a September 11 moment for America".

No, it wasn't. Leaving aside the fact that, as far as I can remember, no-one lost their life in Apollo 13, there is no such thing as "a September 11 moment", except September 11 itself. Nothing comes close to it. It is no good trying to appropriate it. The enormity of the crime that was perpetrated on that day is approached by nothing in recent times. Not even the recent act of terrorism in Boston can be classed as "a September 11 moment".

I do hope this usage doesn't spread.

No, it wasn't. Leaving aside the fact that, as far as I can remember, no-one lost their life in Apollo 13, there is no such thing as "a September 11 moment", except September 11 itself. Nothing comes close to it. It is no good trying to appropriate it. The enormity of the crime that was perpetrated on that day is approached by nothing in recent times. Not even the recent act of terrorism in Boston can be classed as "a September 11 moment".

I do hope this usage doesn't spread.

Saturday, 20 April 2013

In Heaven

Further to my musings about possible heavenly attributes, I'd like to get a bit more specific about the food and drink aspects of heaven:

You have to start the day with double cream and something chocolate, plus a warm croissant and jam, followed by fried eggs and bread, hot, almost overcooked and crispy, the way my grandmother used to make them (but no washing up afterwards, of course, and no smell of frying embedding itself in the curtains). Anything less substantial to eat will leave you feeling very unwell as you start the day.

If you drive at night without drinking, it can seriously impair your skills - you need some gin or vodka before you leave the house, just in case you encounter a breathalyser unit, and on the way home you will need to have tucked away a glass or two of wine as well.

Among the foods needed to keep you thin and healthy, as well as chocolate, cheese and cream, you will have to eat sour snakes regularly, and maybe include from time to time that staple of my boarding school life, brown sugar mixed with butter and spread half an inch thick on toast

And on the question of whether or not you are educated only if you have been educated in science (something that won't figure in my version of heaven), I should point out that that wise writer Marilynne Robinson is quoted here talking about "a kind of parochialism that follows from a belief in science as a kind of magic, as if it existed apart from history and culture, rather than being, in objective truth and inevitability, their product."

You have to start the day with double cream and something chocolate, plus a warm croissant and jam, followed by fried eggs and bread, hot, almost overcooked and crispy, the way my grandmother used to make them (but no washing up afterwards, of course, and no smell of frying embedding itself in the curtains). Anything less substantial to eat will leave you feeling very unwell as you start the day.

If you drive at night without drinking, it can seriously impair your skills - you need some gin or vodka before you leave the house, just in case you encounter a breathalyser unit, and on the way home you will need to have tucked away a glass or two of wine as well.

Among the foods needed to keep you thin and healthy, as well as chocolate, cheese and cream, you will have to eat sour snakes regularly, and maybe include from time to time that staple of my boarding school life, brown sugar mixed with butter and spread half an inch thick on toast

And on the question of whether or not you are educated only if you have been educated in science (something that won't figure in my version of heaven), I should point out that that wise writer Marilynne Robinson is quoted here talking about "a kind of parochialism that follows from a belief in science as a kind of magic, as if it existed apart from history and culture, rather than being, in objective truth and inevitability, their product."

Tuesday, 16 April 2013

Horsing Around

After reacquainting myself with some of my childhood horse books, I turned to A Time of Gifts, by Patrick Leigh Fermor and found him in Vienna, preoccupied with horses too. He includes in his account of his time there this rather wonderful report of a conversation with Ion Pietro Pugliano, who taught Sir Philip Sidney 'horsemanship' in Vienna in 1574. It comes, apparently, from Sidney's Defense of Poesie, and seems to suggest that Sidney could have recognised himself in Didi, just as I did:

"He saide ... what a peerless beast the horse was, the only serviceable Courtier without flattery, the beast of most bewtie, faithfulnesse, courage, and such more, that if I had not beene a peece of a Logician before I came to him, I think he would have perswaded mee to have wished my selfe a horse."

"He saide ... what a peerless beast the horse was, the only serviceable Courtier without flattery, the beast of most bewtie, faithfulnesse, courage, and such more, that if I had not beene a peece of a Logician before I came to him, I think he would have perswaded mee to have wished my selfe a horse."

Sunday, 14 April 2013

Skylar and Richard

This week I read an article in The New Yorker about young people in the United States who are having irreversible surgery and hormone treatment to change their sex. The article dwelt mainly on those who are crossing from female to male, although the process is - or has been - more common in the other direction, partly because it can be done more completely (I will leave the details to your imagination).

The article claims,

'Transgenderism has replaced homosexuality as the newest civil-rights frontier'

and rather tentatively suggests that just possibly there may be influences other than pure muddled biology at work on some of the children who pursue the goal of changing sex. It focussed on one child, now called Skylar, who has been supported in changing from a girl to a boy by their parents, who allowed surgery and hormone treatment when they were, as far as I can tell, fourteen or fifteen. Skylar's mother explains that

'Skylar never wanted to wear a dress.'

Skylar claims to have found puberty 'weird' and, after browsing in Barnes and Noble and finding some young-adult novels about trans kids and then researching on the Internet, came to the conclusion that becoming a boy was the next step to take. As a result of the decision, Skylar has become very in demand and a focus of interest for classmates and the wider world. Attention is something adolescents do love very much.

An alternative case study is also described in the article. She is a girl who was a Tomboy as a child. In the final year of 'an alternative high school' she decided she wanted to become a boy. Her mother tells the writer of the article,

'"I'm still not convinced that it's a good idea to give hormones and assume that, in most cases, it will solve all their problems. I know the clinics giving them out think they're doing something wonderful and saving lives. But a lot of these kids are sad for a variety of reasons. Maybe the gender feelings are the underlying cause, maybe not."'

This conversation took place in a pie shop and, rather chillingly, the author tells us, it was interrupted by

'the college student who'd been studying across from us'

who told them,

'that she, too, was about to transition to male'.

The mother of the Tomboy continued, saying,

'that she had met many teenagers who seemed to regard their bodies as endlessly modifiable, through piercings, or tattoos, or even workout regimens. She wondered if sexual orientation was beginning to seem boring as a form of identity; gay people were getting married, and perhaps seemed too settled.

"The kids who are edgy and funky and drawn to artsy things - these are conversations that are taking place in dorm rooms ... There are tides of history that wash in, and when they wash out they leave some people stranded. The drug culture of the sixties was like that and the sexual culture of the eighties, with AIDS. I think this could be the next wave like that, and I don't want my daughter to be a casualty"'

After reading that article, I read another, this time in Vanity Fair, about Rachel Johnson's troubled editorship of The Lady. Among the many criticisms of Johnson made by the magazine's part owner is that ,

"'You can't get her away from a penis. I think it comes from growing up with all those boys [Johnson has several brothers, including the current Mayor of London]. She is basically a boy. But we didn't pick up on this,'"

Johnson's surprising response to these commments was that they were

'"worryingly accurate": when she was at primary school she refused to wear a dress and made classmates call her Richard.'

And Richard she might have become forever had she been in a different place at a different time.

The article claims,

'Transgenderism has replaced homosexuality as the newest civil-rights frontier'

and rather tentatively suggests that just possibly there may be influences other than pure muddled biology at work on some of the children who pursue the goal of changing sex. It focussed on one child, now called Skylar, who has been supported in changing from a girl to a boy by their parents, who allowed surgery and hormone treatment when they were, as far as I can tell, fourteen or fifteen. Skylar's mother explains that

'Skylar never wanted to wear a dress.'

Skylar claims to have found puberty 'weird' and, after browsing in Barnes and Noble and finding some young-adult novels about trans kids and then researching on the Internet, came to the conclusion that becoming a boy was the next step to take. As a result of the decision, Skylar has become very in demand and a focus of interest for classmates and the wider world. Attention is something adolescents do love very much.

An alternative case study is also described in the article. She is a girl who was a Tomboy as a child. In the final year of 'an alternative high school' she decided she wanted to become a boy. Her mother tells the writer of the article,

'"I'm still not convinced that it's a good idea to give hormones and assume that, in most cases, it will solve all their problems. I know the clinics giving them out think they're doing something wonderful and saving lives. But a lot of these kids are sad for a variety of reasons. Maybe the gender feelings are the underlying cause, maybe not."'

This conversation took place in a pie shop and, rather chillingly, the author tells us, it was interrupted by

'the college student who'd been studying across from us'

who told them,

'that she, too, was about to transition to male'.

The mother of the Tomboy continued, saying,

'that she had met many teenagers who seemed to regard their bodies as endlessly modifiable, through piercings, or tattoos, or even workout regimens. She wondered if sexual orientation was beginning to seem boring as a form of identity; gay people were getting married, and perhaps seemed too settled.

"The kids who are edgy and funky and drawn to artsy things - these are conversations that are taking place in dorm rooms ... There are tides of history that wash in, and when they wash out they leave some people stranded. The drug culture of the sixties was like that and the sexual culture of the eighties, with AIDS. I think this could be the next wave like that, and I don't want my daughter to be a casualty"'

After reading that article, I read another, this time in Vanity Fair, about Rachel Johnson's troubled editorship of The Lady. Among the many criticisms of Johnson made by the magazine's part owner is that ,

"'You can't get her away from a penis. I think it comes from growing up with all those boys [Johnson has several brothers, including the current Mayor of London]. She is basically a boy. But we didn't pick up on this,'"

Johnson's surprising response to these commments was that they were

'"worryingly accurate": when she was at primary school she refused to wear a dress and made classmates call her Richard.'

And Richard she might have become forever had she been in a different place at a different time.

Saturday, 13 April 2013

The Missing

Yesterday I saw an article about mistletoe and its medical potential and I remembered how my dearest friend, not long a mother and desperate for any cure, tried mistletoe as an 'alternative therapy'. It didn't work, but this isn't about the disappointments of alternative therapies. There are acres to be written about that, but I'm not the person to do it.

Instead, what I do know about is the sadness of finding the ones you love most are absent, the strange way that it turns out that they were, in fact, the ones you would always love the best. Some people might argue that our relationships are random, that we choose those that suit us from the choice made available and that we can replace one bright, fun friend with another similar and equally vibrant creature.

My experience, miserably, is otherwise. In my life, I've occasionally found an individual I really get on with. Sometimes it's a relative, sometimes it's a friend. Whatever the link, the thing I've noticed is that, if the bond is truly there, it isn't something that's replaceable. That leaves you feeling very lonely, if someone whom you've discovered is one of those few people you can really call a soul mate suddenly dies on you. Even years later, there is no solution. The voids in your life don't vanish or diminish. If anything, they grow darker and deeper. You can go round them, averting your eyes most of the time, but every now and then it's impossible to ignore them. The spaces where the missing once were remain, unfilled.

Instead, what I do know about is the sadness of finding the ones you love most are absent, the strange way that it turns out that they were, in fact, the ones you would always love the best. Some people might argue that our relationships are random, that we choose those that suit us from the choice made available and that we can replace one bright, fun friend with another similar and equally vibrant creature.

My experience, miserably, is otherwise. In my life, I've occasionally found an individual I really get on with. Sometimes it's a relative, sometimes it's a friend. Whatever the link, the thing I've noticed is that, if the bond is truly there, it isn't something that's replaceable. That leaves you feeling very lonely, if someone whom you've discovered is one of those few people you can really call a soul mate suddenly dies on you. Even years later, there is no solution. The voids in your life don't vanish or diminish. If anything, they grow darker and deeper. You can go round them, averting your eyes most of the time, but every now and then it's impossible to ignore them. The spaces where the missing once were remain, unfilled.

Friday, 12 April 2013

Childhood Reading - Horses

Near the beginning of The Merry-go-round in the Sea the main character gets to know his cousin Didi.

"Didi", he tells us, "was as good as a boy any day. Not that Didi would have wished to be a boy. Her ambition rose higher: she wanted to be a horse"

Ah yes, those were the days. From the age of five or six until around about sixteen, horses were practically all I thought about. I suppose, in contrast to Didi, I was keener to own a horse than to actually be one - and after a brief period of fiasco, during which I was the unwilling and rather grumpy owner of a donkey, (a period when I began to believe that one of my favourite books, Half Magic, which I'll write about another day, but which, in essence, tells the tale of some children who find a wishing talisman that gives them exactly half of anything they wish for, might actually not be fiction but truth), I did end up with my own four-legged equine friend.

But where did this passion for horses come from? Partly, I suppose, from spending too much time with my pony clubbing older cousin, with whom I stayed most holidays. But partly too it derived from being overwhelmed by books about horses from the moment I could read.

I still have many of them. They divide into three main categories of story.

First, there are the ones that are told from the horse's point of view and relate the ups and downs of some noble pony's life:

The origin of this model was I suspect Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, and most examples of the type share with that book an earnest desire to improve the treatment of horses. Their stories usually involve a progression from initial happiness to separation from good masters, followed by many travails and injustices, concluding either with reunion with the original kind owners or happiness in a new home with equally decent souls.

On the way to the inevitable happy ending the reader must endure scenes of great catastrophe as fine equines are forced to pull milk carts or made to put up with spoilt, rude children who rename them 'Nigger' and don't notice when they are cut and bleeding. Running throughout all these narratives is a strong assumption that reader and horse share a common understanding of fair play and how things ought to be done, plus a love of the outdoors. I wonder if similar books were ever written anywhere other than England - the place of paramount importance that is given to the kind treatment of animals in these texts is surely very particular to English culture.

Incidentally, looking through the examples of this type of horse story on my shelves, there is one that turns out to be a little out of the ordinary. Until just now, I had no idea that its author was only eleven years old when she wrote it:

Published in 1930, it strikes me as a testament to literacy standards in those days. Here, for example, is the opening paragraph:

"The wind howled across the desolate moor and the grey feathery clouds ran wild races in the tumultuous skies. Here and there a weather-beaten bush or puny sprig stood up in contrast with a bare grey rock or sheet of ice, and in less exposed spots sullen bogs were visible. The whole aspect presented a formidable appearance."

I'm not sure many eleven year olds could command such a vocabulary now. On the other hand, they also would be unlikely to display quite such unthinking snobbery:

"Tally Ho saw his new master step forward. He was a youngish man, tall, slight, and fair, with high cheekbones and a deep low voice. Although obviously not a gentleman, he was distinctly good-looking".

The next variety of horse book I was exposed to were the books that merely masqueraded as stories about horses while trying, rather unsuccessfully, to conceal their real intent, which was to shove as much geography as they could into the heads of their young horse-mad readers:

Asido is the most blatant in this regard and therefore the one I remember least enjoying. Take these passages as examples of the kind of unentertaining stuff the author thought he could slip by us readers:

"Here and there the dead stalk of a century plant, gaunt and tall as a telegraph pole, towered above the rest. A strange plant this, earning its name by its habit of flowering only once perhaps in fifty years or more; the agave or maguey as it is more commonly called in Mexico, where it is put to many uses, the chief of which is the manufacture of pulque, a fermented drink resembling cider."

"The oil well ... was situated on Point Banda, the headland on the opposite side of Todos Santos Bay from Ensenada, and the road there ran some seven miles along the coast. One gets accustomed to seeing these ugly, great derricks cropping up in all sorts of places in California and Mexico. Sometimes large tracts of land, such as the famous Signal Hill district, are a mass of them, standing so closely together that they have the appearance of a dead pine forest, hideous in the day-time, but strangely attractive and eerie at night, when each tower, almost invisible itself in the darkness, is crowned with a lamp. Sometimes one sees a stray derrick in a back garden in a residential district, sometimes on a mountain-side, but where they look queerest of all is on the seashore. It seems so incongruous that oil should be found beneath wave-washed sand.'

I mean talk about yawn. I wanted a story about a horse, not about Mexican oil fields (although I find that passage quite evocative now) and Mexico's flora and fauna. The thing reads like a guidebook rather than an adventure a lot of the time:

"The road was wider and smoother now, and showed some evidence of work having been done on it, and it was easier to recognise the wonderful El Camino Real - the Royal Road. This great highway which stretches all the way along the Pacific seaboard from Ensenada to above the Canadian border, is the work of the old Spanish padres who built it and the hundreds of missions that it passes, as they carried Christianity further and further north. That part of it which is in the United States has been preserved as a national memorial, and is marked at frequent intervals by large bronze replicas of the mission bell. Here in Mexico it is only use and occasional care of the padres which keep its memory alive. Cultivated fields of maize and beans ..."

Khyberie is better, although it contains, I realise on looking at it again, a surprising amount of political stuff about the North West Frontier, which went straight over my head as a child, (but then I managed to read the entire Narnia series without ever picking up a hint of Christian allegory).

I now discover that Khyberie (a pony from Badakshan) and his friend Alexander, a Waler (a lovely breed with a slightly tragic history), have several quite extensive conversations about the essentially unstable nature of the region and the 'explosive forces on the North-West Indian Frontier.' If only some of our current Defence strategists had heeded the whinnies of these two wise creatures.

Phari, the Adventures of a Tibetan Pony, is rather less sophisticated than Khyberie. While the author of Khyberie has a good word or two to say for Khyberie's original owners in Badakshan, the author of Phari has apparently never contemplated the idea that any race but the British should ever be taken seriously.

The text is littered with generalisations - 'He had a round flat face like all Tibetans' - and the plot hinges on the activities of useless natives - 'Hussain Ali ... a fat, jovial Mussulman ... was a past master in the art of putting things off' - and dishonest dealers, such as Mirza Khan, 'a picturesque ruffian ... clad in a spotless white loin-cloth, with a russet coloured blanket flung over his broad shoulders [and a] face ... the colour of deep mahogany', who rustles Phari and declares, like a pantomime villain, 'The sahib will never see him again.'

Even amongst the Britons, the non-officer class is sent up with absurd renderings of what I assume is supposed to be Cockney English - 'I'll massage 'im, and put on hot forminashuns and the like, anything you may order, only let me 'ave a try at 'im. It can't do no 'arm ...'

However, the ending is moving and also reveals, through the medium of a horse's mind, the confusing fondness that many of the colonial class ended up developing for their second homeland in India:

'Back in his stable the old grey pony ... would ... let his mind travel back...He would cross again the wind-swept, frozen passes, gallop round the track at Darjeeling, or hear the click of the polo stock during that first triumph of his with the Planters' Team ... He would feel the twinge of his old wound, and remember even that terrible march across India without bitterness.'

.

The third main category of horse book with which I learnt to read comprises adventure stories in which young riders rather than young horses are the protagonists. These books could be described as Swallows and Amazons on dry land, with hooved companions replacing boats, (although I think, sacrilegiously, that Swallows and Amazons is rather less entertaining than these tales):

Unfortunately, whereas a thoughtless tendency to discount other cultures is on display in the horse/geography books, in these horse/adventure books snobbery is the unattractive trait that I can't help noticing these days, my antennae for all such slurs having been intensively honed and polished by the authorities since the innocent days of my youth.

In Riding with Reka, for example, the author thinks nothing of describing someone as wearing their hat at 'an "oiky" angle', whilst two other characters are described as looking 'as though they had stepped out of a cheap sale catalogue'.

The assumptions made by the writer about the reader's own class and views are enormous really. Take this passage as an example:

"There was an amusing incident one week-end when a large party of Cockneys arrived for the day. A button-holed, bewhiskered gentleman was swaggering along the beach with a stout, paper-capped lady who was shedding orange peel wherever she went. Reka happened to be trotting by when a playful gust of wind blew the cap straight at him... He pranced about in the middle of the trippers making them shout frantically and scatter about in all directions."

Hilarious to think of - the common folk screaming, so droll.

A similar sense of otherness is expressed in relation to gypsies in The Ponies of Bunts, although to be fair the gypsies are not treated as figures of fun so much as strange outsiders. For example, this dialogue from the book makes some attempt to try to see things from the gypsy point of view:

"'What do gypsies live on?' [Derek] enquired. 'Do they work?'

'Well, it's rather difficult to know,' said Jenefer. 'They don't do any regular work, and their enemies say they live by poaching and robbing hen-roosts; I daresay that does help them, but the women go about selling wooden washing pegs and other trifles that the men make, and a gypsy like Isaacs makes a good deal of money buying and selling horses. He's the best judge of a pony or a horse for miles round, and if you tell him you are on the look-out for one, he is certain to bring the very animal you want in a day or two. He is very clever.'"

However, ultimately it does turn out that it is the gypsies who have been pinching the protagonists' ponies. On the other hand, gypsies pinching ponies may well have been true to life at the time, rather than an outrageous fictitious slur.

Sometimes of course, there is a volume that does not quite fit any particular category. Into this pile I would place Broncho:

Published in 1930, Broncho is quite an odd piece of work to offer to children, dealling, as it does, with the First World War. The book is dedicated:

'To horses of "all ranks" who served in the great war, all of whom suffered and few of whom survived. Amongst the survivors is the real Broncho, whos name has - in all humility - been given to the "hero" of this fictititious tale, since it is to him that it owes its inspiration.'

It tells the story of the relationship between a horse called Broncho and a young man called Roger, who takes him to the Western Front, (to the area around Bapaume, where my grandfather served, although I'd never picked up the link until now). Through Broncho - not Roger, who vanishes from the narrative for a while - the child reader is introduced to the Great War and then to shell shock, which the horse suffers. Of course, as with all good horse stories, eventually Broncho and Roger are reunited. Furthermore, thanks to Broncho, Roger makes the acquaintance of Danny, with whom he sets up house and they all live happily ever after, make of that what you will.

I suppose it's hardly surprising these books seem out of date now. After all they all belonged originally to my mother and she is well over 80. However, even though she read them so long ago, when I mentioned them to her the other day, her eyes filled with pleasure, as she recalled her favourites. "Have you got Moorland Mousie?' she asked, 'I loved Moorland Mousie. There was a beautiful frontispiece showing just her head.'

There was too, and here it is:

(And I should point out that one of the virtues of all these books is the illustrations - which most often were contributed by either Lionel Edwards or Cecil Aldin, both of them very, very good draughtsmen, who produced really lovely pictures to accompany the texts).

"And what about The Ponies of Bunt', my mother went on, 'have you kept that one? I was so thrilled with that one because it had photographs.' Her eyes were dancing by now. 'It made the story so real.'

Like my mother, I too reserve a special enthusiasm for the books I discovered in my childhood. There is something magical about those early years of reading when you first realise that there are many wonderful, alternative, imagined worlds to be found inside books. Occasionally from now on I'll post some more about things I read in childhood. It may be a sign of my arrested development, but most of my absolute favourite books are things I read before the age of sixteen.

"Didi", he tells us, "was as good as a boy any day. Not that Didi would have wished to be a boy. Her ambition rose higher: she wanted to be a horse"

Ah yes, those were the days. From the age of five or six until around about sixteen, horses were practically all I thought about. I suppose, in contrast to Didi, I was keener to own a horse than to actually be one - and after a brief period of fiasco, during which I was the unwilling and rather grumpy owner of a donkey, (a period when I began to believe that one of my favourite books, Half Magic, which I'll write about another day, but which, in essence, tells the tale of some children who find a wishing talisman that gives them exactly half of anything they wish for, might actually not be fiction but truth), I did end up with my own four-legged equine friend.

But where did this passion for horses come from? Partly, I suppose, from spending too much time with my pony clubbing older cousin, with whom I stayed most holidays. But partly too it derived from being overwhelmed by books about horses from the moment I could read.

I still have many of them. They divide into three main categories of story.

First, there are the ones that are told from the horse's point of view and relate the ups and downs of some noble pony's life:

The origin of this model was I suspect Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, and most examples of the type share with that book an earnest desire to improve the treatment of horses. Their stories usually involve a progression from initial happiness to separation from good masters, followed by many travails and injustices, concluding either with reunion with the original kind owners or happiness in a new home with equally decent souls.

On the way to the inevitable happy ending the reader must endure scenes of great catastrophe as fine equines are forced to pull milk carts or made to put up with spoilt, rude children who rename them 'Nigger' and don't notice when they are cut and bleeding. Running throughout all these narratives is a strong assumption that reader and horse share a common understanding of fair play and how things ought to be done, plus a love of the outdoors. I wonder if similar books were ever written anywhere other than England - the place of paramount importance that is given to the kind treatment of animals in these texts is surely very particular to English culture.

Incidentally, looking through the examples of this type of horse story on my shelves, there is one that turns out to be a little out of the ordinary. Until just now, I had no idea that its author was only eleven years old when she wrote it:

Published in 1930, it strikes me as a testament to literacy standards in those days. Here, for example, is the opening paragraph:

"The wind howled across the desolate moor and the grey feathery clouds ran wild races in the tumultuous skies. Here and there a weather-beaten bush or puny sprig stood up in contrast with a bare grey rock or sheet of ice, and in less exposed spots sullen bogs were visible. The whole aspect presented a formidable appearance."

I'm not sure many eleven year olds could command such a vocabulary now. On the other hand, they also would be unlikely to display quite such unthinking snobbery:

"Tally Ho saw his new master step forward. He was a youngish man, tall, slight, and fair, with high cheekbones and a deep low voice. Although obviously not a gentleman, he was distinctly good-looking".

The next variety of horse book I was exposed to were the books that merely masqueraded as stories about horses while trying, rather unsuccessfully, to conceal their real intent, which was to shove as much geography as they could into the heads of their young horse-mad readers:

Asido is the most blatant in this regard and therefore the one I remember least enjoying. Take these passages as examples of the kind of unentertaining stuff the author thought he could slip by us readers:

"Here and there the dead stalk of a century plant, gaunt and tall as a telegraph pole, towered above the rest. A strange plant this, earning its name by its habit of flowering only once perhaps in fifty years or more; the agave or maguey as it is more commonly called in Mexico, where it is put to many uses, the chief of which is the manufacture of pulque, a fermented drink resembling cider."

"The oil well ... was situated on Point Banda, the headland on the opposite side of Todos Santos Bay from Ensenada, and the road there ran some seven miles along the coast. One gets accustomed to seeing these ugly, great derricks cropping up in all sorts of places in California and Mexico. Sometimes large tracts of land, such as the famous Signal Hill district, are a mass of them, standing so closely together that they have the appearance of a dead pine forest, hideous in the day-time, but strangely attractive and eerie at night, when each tower, almost invisible itself in the darkness, is crowned with a lamp. Sometimes one sees a stray derrick in a back garden in a residential district, sometimes on a mountain-side, but where they look queerest of all is on the seashore. It seems so incongruous that oil should be found beneath wave-washed sand.'

I mean talk about yawn. I wanted a story about a horse, not about Mexican oil fields (although I find that passage quite evocative now) and Mexico's flora and fauna. The thing reads like a guidebook rather than an adventure a lot of the time:

"The road was wider and smoother now, and showed some evidence of work having been done on it, and it was easier to recognise the wonderful El Camino Real - the Royal Road. This great highway which stretches all the way along the Pacific seaboard from Ensenada to above the Canadian border, is the work of the old Spanish padres who built it and the hundreds of missions that it passes, as they carried Christianity further and further north. That part of it which is in the United States has been preserved as a national memorial, and is marked at frequent intervals by large bronze replicas of the mission bell. Here in Mexico it is only use and occasional care of the padres which keep its memory alive. Cultivated fields of maize and beans ..."

Khyberie is better, although it contains, I realise on looking at it again, a surprising amount of political stuff about the North West Frontier, which went straight over my head as a child, (but then I managed to read the entire Narnia series without ever picking up a hint of Christian allegory).

I now discover that Khyberie (a pony from Badakshan) and his friend Alexander, a Waler (a lovely breed with a slightly tragic history), have several quite extensive conversations about the essentially unstable nature of the region and the 'explosive forces on the North-West Indian Frontier.' If only some of our current Defence strategists had heeded the whinnies of these two wise creatures.

Phari, the Adventures of a Tibetan Pony, is rather less sophisticated than Khyberie. While the author of Khyberie has a good word or two to say for Khyberie's original owners in Badakshan, the author of Phari has apparently never contemplated the idea that any race but the British should ever be taken seriously.

The text is littered with generalisations - 'He had a round flat face like all Tibetans' - and the plot hinges on the activities of useless natives - 'Hussain Ali ... a fat, jovial Mussulman ... was a past master in the art of putting things off' - and dishonest dealers, such as Mirza Khan, 'a picturesque ruffian ... clad in a spotless white loin-cloth, with a russet coloured blanket flung over his broad shoulders [and a] face ... the colour of deep mahogany', who rustles Phari and declares, like a pantomime villain, 'The sahib will never see him again.'

Even amongst the Britons, the non-officer class is sent up with absurd renderings of what I assume is supposed to be Cockney English - 'I'll massage 'im, and put on hot forminashuns and the like, anything you may order, only let me 'ave a try at 'im. It can't do no 'arm ...'

However, the ending is moving and also reveals, through the medium of a horse's mind, the confusing fondness that many of the colonial class ended up developing for their second homeland in India:

'Back in his stable the old grey pony ... would ... let his mind travel back...He would cross again the wind-swept, frozen passes, gallop round the track at Darjeeling, or hear the click of the polo stock during that first triumph of his with the Planters' Team ... He would feel the twinge of his old wound, and remember even that terrible march across India without bitterness.'

.

The third main category of horse book with which I learnt to read comprises adventure stories in which young riders rather than young horses are the protagonists. These books could be described as Swallows and Amazons on dry land, with hooved companions replacing boats, (although I think, sacrilegiously, that Swallows and Amazons is rather less entertaining than these tales):

Unfortunately, whereas a thoughtless tendency to discount other cultures is on display in the horse/geography books, in these horse/adventure books snobbery is the unattractive trait that I can't help noticing these days, my antennae for all such slurs having been intensively honed and polished by the authorities since the innocent days of my youth.

In Riding with Reka, for example, the author thinks nothing of describing someone as wearing their hat at 'an "oiky" angle', whilst two other characters are described as looking 'as though they had stepped out of a cheap sale catalogue'.

The assumptions made by the writer about the reader's own class and views are enormous really. Take this passage as an example:

"There was an amusing incident one week-end when a large party of Cockneys arrived for the day. A button-holed, bewhiskered gentleman was swaggering along the beach with a stout, paper-capped lady who was shedding orange peel wherever she went. Reka happened to be trotting by when a playful gust of wind blew the cap straight at him... He pranced about in the middle of the trippers making them shout frantically and scatter about in all directions."

Hilarious to think of - the common folk screaming, so droll.

A similar sense of otherness is expressed in relation to gypsies in The Ponies of Bunts, although to be fair the gypsies are not treated as figures of fun so much as strange outsiders. For example, this dialogue from the book makes some attempt to try to see things from the gypsy point of view:

"'What do gypsies live on?' [Derek] enquired. 'Do they work?'

'Well, it's rather difficult to know,' said Jenefer. 'They don't do any regular work, and their enemies say they live by poaching and robbing hen-roosts; I daresay that does help them, but the women go about selling wooden washing pegs and other trifles that the men make, and a gypsy like Isaacs makes a good deal of money buying and selling horses. He's the best judge of a pony or a horse for miles round, and if you tell him you are on the look-out for one, he is certain to bring the very animal you want in a day or two. He is very clever.'"

However, ultimately it does turn out that it is the gypsies who have been pinching the protagonists' ponies. On the other hand, gypsies pinching ponies may well have been true to life at the time, rather than an outrageous fictitious slur.

Sometimes of course, there is a volume that does not quite fit any particular category. Into this pile I would place Broncho:

Published in 1930, Broncho is quite an odd piece of work to offer to children, dealling, as it does, with the First World War. The book is dedicated:

'To horses of "all ranks" who served in the great war, all of whom suffered and few of whom survived. Amongst the survivors is the real Broncho, whos name has - in all humility - been given to the "hero" of this fictititious tale, since it is to him that it owes its inspiration.'

It tells the story of the relationship between a horse called Broncho and a young man called Roger, who takes him to the Western Front, (to the area around Bapaume, where my grandfather served, although I'd never picked up the link until now). Through Broncho - not Roger, who vanishes from the narrative for a while - the child reader is introduced to the Great War and then to shell shock, which the horse suffers. Of course, as with all good horse stories, eventually Broncho and Roger are reunited. Furthermore, thanks to Broncho, Roger makes the acquaintance of Danny, with whom he sets up house and they all live happily ever after, make of that what you will.

I suppose it's hardly surprising these books seem out of date now. After all they all belonged originally to my mother and she is well over 80. However, even though she read them so long ago, when I mentioned them to her the other day, her eyes filled with pleasure, as she recalled her favourites. "Have you got Moorland Mousie?' she asked, 'I loved Moorland Mousie. There was a beautiful frontispiece showing just her head.'

There was too, and here it is:

(And I should point out that one of the virtues of all these books is the illustrations - which most often were contributed by either Lionel Edwards or Cecil Aldin, both of them very, very good draughtsmen, who produced really lovely pictures to accompany the texts).

"And what about The Ponies of Bunt', my mother went on, 'have you kept that one? I was so thrilled with that one because it had photographs.' Her eyes were dancing by now. 'It made the story so real.'

|

| Personally, I'd have stuck with the Cecil Aldin/Lionel Edwards illustrations |

Like my mother, I too reserve a special enthusiasm for the books I discovered in my childhood. There is something magical about those early years of reading when you first realise that there are many wonderful, alternative, imagined worlds to be found inside books. Occasionally from now on I'll post some more about things I read in childhood. It may be a sign of my arrested development, but most of my absolute favourite books are things I read before the age of sixteen.

Tuesday, 9 April 2013

Filums

The ACT government in its wisdom has allowed a new cinema to be set up in a part of town that has absolutely no restaurants - it is on the bottom of a rather flash multi-storey set of flats, which has been positioned right by a freeway, at just enough distance from the city centre to ensure that the entire area is absolutely dead (apart from the drone from the freeway) in the evening.

I assume the flats come equipped with kitchens as there won't be any alternative source of hot food available nearby - despite the fact that I've read that young apartment dwellers prefer eating out these days. I certainly like to see a film and then have dinner - or have dinner and then see a film. I prefer not to have dinner at my house on these occasions, but to spend the entire evening out. Canberra's town planners, God bless them, are presumably keen for us all to get back into home cooking though - or concerned to lower the break-in rate by chivvying us back into our houses as quickly as possible.

Once again, in this overplanned city, it strikes me that things might have been better had there been no planners to prevent the place from developing higgledy piggledy. Having armies of the pernicious breed seems just to slow everything down and produce the kind of hopeless outcome that is this new cinema, place as far as possible from everything else.

Anyway, the cinema shows lots of 'art house' movies so I am determined to support it. I like 'art house' movies. I wasn't sure if I did, but having this last fortnight been to three movies, I can definitely say that I do.

The first movie we went to was 'The Loneliest Planet'. It was adapted from a short story and concerned a youngish couple, she American, he Spanish-speaking. We were told almost nothing about them, which some in our party found irritating but I found excellent, as I think they were supposed to be emblematic of a certain kind of young Westerner, the kind who become perpetual travellers, only ever stopping to make enough money to set off again. The two in the film were travelling in Georgia and we found them at the beginning preparing to embark on a walk through the Georgian landscape with a guide.

Nothing at all happens - or very little (apparently the trailer urges viewers not to give away the big event, but I'm afraid I missed it). The Georgian scenery is extraordinary and almost makes the film worthwhile on its own.

The point of this kind of endless travelling is revealed as fairly problematic - no-one seems to be really enjoying themselves, no-one really seems to understand what they are seeing. By the end, the couple's endless wandering appeared, to me at least, to be a modern version of the old pastime of going to Bedlam and staring at the inmates. For them, the whole non-Western world seems to represent a kind of zoo whose inmates they peer at. In a bar, they dance with the locals, but all the time smirking at their outlandish foreign ways. A ball flies over a wall they are walking past and they chuck it back, only for it to fly out again. For a few minutes, they join in what they assume is a game with people they don't know and can't see. The young Spanish speaker, upon being asked about what kind of car he has by the Georgian guide, replies smugly, 'A bicycle.' The guide, on the other hand, wants nothing more than to get his hands on a nice big shiny Western car. The Westerners romanticise the simplicity they find. The natives wish to escape it, on the whole - or at least to grab some of what these young people disdain.

The next movie we went to was 'Barbara', about a dissident female doctor in East Germany in the 1980s. The doctor has been banished to a rural hospital from Berlin. The film is rather beautiful to look at and quietly reveals the banal but grinding nastiness of the old East German regime. This might suggest it is grim or dull, but it isn't; it is gripping and moving and very well worth seeing.

Finally, we went to see Side Effects. It wasn't bad, a nice little thriller, but it all seemed so frantic and flashy and shiny after the first two. Each of them sent me home in a faintly contemplative mood. Something about their slow, thoughtful camera work made me more aware of my surroundings afterwards, so that the act of putting on the kettle or washing a peach took on some peculiar kind of weight. They each in a way had the effect of a Vermeer painting, because in each the camera had lingered on small details, domestic scenes or faces, allowing you to see how each instant of an individual existence can be framed and seen as significant, how each moment has importance.

Side Effects had different intentions. It was all about exciting you and distracting you from reality. I emerged blinking from the theatre, feeling as if I'd been on one of those funfair rides that turn you upside down and whirl you around and then hurl you back to ground with a jolt.

Side Effects probably cost far more to make than Barbara or The Loneliest Planet, it probably involved far more ingenuity to construct than those two, but perhaps it was the kind of ingenuity that Les Murray describes (I think, although I can't find the reference) as 'front brain' rather than 'back brain'.

Up the back, that's where I like to be.

I assume the flats come equipped with kitchens as there won't be any alternative source of hot food available nearby - despite the fact that I've read that young apartment dwellers prefer eating out these days. I certainly like to see a film and then have dinner - or have dinner and then see a film. I prefer not to have dinner at my house on these occasions, but to spend the entire evening out. Canberra's town planners, God bless them, are presumably keen for us all to get back into home cooking though - or concerned to lower the break-in rate by chivvying us back into our houses as quickly as possible.

Once again, in this overplanned city, it strikes me that things might have been better had there been no planners to prevent the place from developing higgledy piggledy. Having armies of the pernicious breed seems just to slow everything down and produce the kind of hopeless outcome that is this new cinema, place as far as possible from everything else.

Anyway, the cinema shows lots of 'art house' movies so I am determined to support it. I like 'art house' movies. I wasn't sure if I did, but having this last fortnight been to three movies, I can definitely say that I do.

The first movie we went to was 'The Loneliest Planet'. It was adapted from a short story and concerned a youngish couple, she American, he Spanish-speaking. We were told almost nothing about them, which some in our party found irritating but I found excellent, as I think they were supposed to be emblematic of a certain kind of young Westerner, the kind who become perpetual travellers, only ever stopping to make enough money to set off again. The two in the film were travelling in Georgia and we found them at the beginning preparing to embark on a walk through the Georgian landscape with a guide.

Nothing at all happens - or very little (apparently the trailer urges viewers not to give away the big event, but I'm afraid I missed it). The Georgian scenery is extraordinary and almost makes the film worthwhile on its own.

The point of this kind of endless travelling is revealed as fairly problematic - no-one seems to be really enjoying themselves, no-one really seems to understand what they are seeing. By the end, the couple's endless wandering appeared, to me at least, to be a modern version of the old pastime of going to Bedlam and staring at the inmates. For them, the whole non-Western world seems to represent a kind of zoo whose inmates they peer at. In a bar, they dance with the locals, but all the time smirking at their outlandish foreign ways. A ball flies over a wall they are walking past and they chuck it back, only for it to fly out again. For a few minutes, they join in what they assume is a game with people they don't know and can't see. The young Spanish speaker, upon being asked about what kind of car he has by the Georgian guide, replies smugly, 'A bicycle.' The guide, on the other hand, wants nothing more than to get his hands on a nice big shiny Western car. The Westerners romanticise the simplicity they find. The natives wish to escape it, on the whole - or at least to grab some of what these young people disdain.

The next movie we went to was 'Barbara', about a dissident female doctor in East Germany in the 1980s. The doctor has been banished to a rural hospital from Berlin. The film is rather beautiful to look at and quietly reveals the banal but grinding nastiness of the old East German regime. This might suggest it is grim or dull, but it isn't; it is gripping and moving and very well worth seeing.

Finally, we went to see Side Effects. It wasn't bad, a nice little thriller, but it all seemed so frantic and flashy and shiny after the first two. Each of them sent me home in a faintly contemplative mood. Something about their slow, thoughtful camera work made me more aware of my surroundings afterwards, so that the act of putting on the kettle or washing a peach took on some peculiar kind of weight. They each in a way had the effect of a Vermeer painting, because in each the camera had lingered on small details, domestic scenes or faces, allowing you to see how each instant of an individual existence can be framed and seen as significant, how each moment has importance.

Side Effects had different intentions. It was all about exciting you and distracting you from reality. I emerged blinking from the theatre, feeling as if I'd been on one of those funfair rides that turn you upside down and whirl you around and then hurl you back to ground with a jolt.

Side Effects probably cost far more to make than Barbara or The Loneliest Planet, it probably involved far more ingenuity to construct than those two, but perhaps it was the kind of ingenuity that Les Murray describes (I think, although I can't find the reference) as 'front brain' rather than 'back brain'.

Up the back, that's where I like to be.

Monday, 8 April 2013

Blame It On the Cleaner

Our local shops is a constant source of wonder. The latest offering is this ad for an all-round factotum, willing not only to iron and babysit but also very happy to take responsibility for any misdemeanours:

Or is there a 'p' missing and she's just good at getting under furniture and round corners? How disappointing. I was hoping for all my sins to be absolved.

Finders Keepers

Having been alerted to the new non-creative approach to writing, I now am seeing bits of 'literature' trapped inside every bit of prose that I read. For instance, here is a 'poem', rescued from a review of a book about leaves I just read in the 7 February 2013 London Review of Books:

Unlike an animal, a leaf

is absolutely stuck

with its lot:

it cannot seek

shade when the sun gets

too hot,

it cannot go in search

of water

when the rains don't come

it cannot run away

from predators.

Poor leaves. I'd never thought of what a rotten time they have till I read that. Which is why I was moved to 'write' a 'poem'. Using someone else's words.

Unlike an animal, a leaf

is absolutely stuck

with its lot:

it cannot seek

shade when the sun gets

too hot,

it cannot go in search

of water

when the rains don't come

it cannot run away

from predators.

Poor leaves. I'd never thought of what a rotten time they have till I read that. Which is why I was moved to 'write' a 'poem'. Using someone else's words.

Friday, 5 April 2013

So Much to Show You - Things I've Found on the Internet Since 23 February, 2013

There's a new affectation I've noticed that is very like the old one that people had of saying, 'Oh, I never watch television', their tone implying that watching television was an activity that was a little shameful. This new variant of that old trick is to say, 'You're on Twitter are you. Yes. I don't get Twitter'. This statement is made in such a way that the listener understands that not only does the speaker believe that they actually do "get" Twitter but that what they get about it is that it is a mind rotting waste of time.

Twitter definitely is a waste of time, in a way, but, far from being mind rotting, I would argue that it is quite mind broadening. The reason it is a waste of time is also the reason that it is mind broadening: it provides links to many, many things on the Internet that I would otherwise never see.

Many of the things Twitter links me to are fascinating, some merely funny, (and really, as Elberry shows us, [see point 2 here] 'merely' is the wrong word there, since wit, unlike seriousness, cannot be faked). Following these links does absorb time, but I don't really begrudge time spent reading - especially if I end up reading things that are beautiful or stimulating, thought-provoking or, indeed, introduce me to whole new ways of thinking, (even better, if they make me laugh).

And so to what I've found lately:

1. I've been reading Stephen Grosz's book and moderately enjoying it. However, as yet I haven't come across a piece in the book that is as fine as this one. He published it in Granta and I came across it thanks to a tweet from @drearyagent, whose tweets often lead to interesting links.

2. Another tweeter who regularly comes up with interesting things is @brainpicker, (even though the name makes me wince slightly). One of them was this letter, which is wonderful, even if it probably provided rather small comfort for poor old farflung Plorn. Another was some letters from EB White, including this one about editing:

"Dear Mr. –

It comes down to the meaning of ‘needless.’ Often a word can be removed without destroying the structure of a sentence, but that does not necessarily mean that the word is needless or that the sentence has gained by its removal.

If you were to put a narrow construction on the word ‘needless,’ you would have to remove tens of thousands of words from Shakespeare, who seldom said anything in six words that could be said in twenty. Writing is not an exercise in excision, it’s a journey into sound. How about ‘tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’*? One tomorrow would suffice, but it’s the other two that have made the thing immortal.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for your letter.

Yrs,

E. B. White"

3. Someone retweeted something by @BryanAppleyard and that led me to this, which I like for the alternating photographs at the bottom. It seems to me that they give you sense of how exciting it must be to be a working actor, taking on different roles and being in different productions as a way of life, while at the same time highlighting how you can be very successful without achieving great fame.

4. I found the thesis of this, very intriguing. Can all this really be true, or is the whole thing an elaborate April Fool's Day joke: