I like my regular trips to Yass. Apart from the pleasures described so eloquently by Mr C Richard, there is always the excitement of witnessing the latest evidence of the education revolution at work:

I also enjoy the feelings of poignance that advertisements like these evoke in me (and what, I can't help wondering, do the inverted commas around the word 'live' signify in the second picture?):

I am sobered by the way in which notices like this remind me that, while city folk think they're so clever, they actually know nothing - there is a whole other language being spoken in rural Australia that few of us in the urban world even begin to understand:

Best of all, today, in this advertisement for guinea pigs:

I came face to face with my spiritual doppelganger:

While I'd have to admit that the one in the photograph has got her hair under control a bit better than I have, the look on her face, that expression of utter, overwhelming confusion, it's exactly the same one that I see whenever I look in the mirror.

It's comforting, somehow, to think that huddled in a hutch somewhere in Binalong there is a small, furry kindred spirit who is just as unable to make sense of existence - or hair care - as me.

Thursday, 28 February 2013

Tuesday, 26 February 2013

The Joy of Babel II

Yesterday, when we were watching the news about the Italian election, Mr Monti appeared on the screen. "What's the Italian for 'boring'?", my husband asked. "'Noioso,'" I said, 'or possibly 'fastidioso', although I think that means more irritating and tedious than dull exactly."

"What's the Italian word for 'fastidious' then, if 'fastidioso' means annoying?" my husband asked. We looked it up in my ancient and rather useless dictionary (so useless that when you look up 'boring' in the English section, all you get is an engineering term) and also in the electronic dictionary that came with my e-reader.

What we found illustrates one of the things I love about learning languages - the way in which underlying differences in the outlook of the speakers of another language are revealed in the language itself. In this case, almost all the words listed to translate the English concept 'fastidious' into Italian - 'difficile', 'esigente', 'schifiltoso' (which presumably comes from 'schifo') and 'incontentabile' - were negative.

The Italian language clearly assumes that its speakers will see someone who is fastidious in their approach to life and work - (the kind of person that I, as an editor, would regard as the apex of humankind) - as difficult and hard to please. The thing that interests me is whether this detail suggests that Italians actually regard the fastidious as a bit of a pain or whether it is just their language that prevents them from viewing such people in a more positive light. Do we shape language or does language shape us?

"What's the Italian word for 'fastidious' then, if 'fastidioso' means annoying?" my husband asked. We looked it up in my ancient and rather useless dictionary (so useless that when you look up 'boring' in the English section, all you get is an engineering term) and also in the electronic dictionary that came with my e-reader.

What we found illustrates one of the things I love about learning languages - the way in which underlying differences in the outlook of the speakers of another language are revealed in the language itself. In this case, almost all the words listed to translate the English concept 'fastidious' into Italian - 'difficile', 'esigente', 'schifiltoso' (which presumably comes from 'schifo') and 'incontentabile' - were negative.

The Italian language clearly assumes that its speakers will see someone who is fastidious in their approach to life and work - (the kind of person that I, as an editor, would regard as the apex of humankind) - as difficult and hard to please. The thing that interests me is whether this detail suggests that Italians actually regard the fastidious as a bit of a pain or whether it is just their language that prevents them from viewing such people in a more positive light. Do we shape language or does language shape us?

Monday, 25 February 2013

Limited Value

Usually, when learning a language, I am a dutiful plodder, accepting unquestioningly the rules of grammar and completing the dull exercises I'm set without a second thought. However, yesterday, as I was ploughing my way through a chapter on the Hungarian imperative in one of my Teach-Yourself-Hungarian-type books, I did find myself wondering about the verbs that had been chosen to illustrate the different classes of conjugation.

I mean, how likely is that I'm ever going to order anyone to do some milking, or indeed exclaim cheerfully, 'Let us milk'? And I trust I'm right in assuming that I'm never going to need to use the word 'kill' in any context, least of all the imperative - or is it a rule that, once in possession of knowledge, one will inevitably put that knowledge to use?

I mean, how likely is that I'm ever going to order anyone to do some milking, or indeed exclaim cheerfully, 'Let us milk'? And I trust I'm right in assuming that I'm never going to need to use the word 'kill' in any context, least of all the imperative - or is it a rule that, once in possession of knowledge, one will inevitably put that knowledge to use?

Things I Discovered on the Internet February 17 to 24, 2013

To unoriginally paraphrase the words of this oddly lovable man, this week I have been mostly too busy to thoroughly surf the Internet, which has been annoying.

However, I did squeeze in a few short and refreshing mini-surfs, during which I found this, and this, (ignore the preceding advertisement), and this. Reading the last one, it struck me that there is a reluctance to pander for popularity about Clive James's attitude these days (perhaps it was there always and has only become very noticeable recently) that reminds me more and more of Les Murray. Two extraordinarily brilliant independent thinkers (who also happen to be Australian - or is being Australian the single important element that makes them contrarians?) in a largely thoughtless and conformist world.

Oh, and my daughter just sent me this pretty site, which she designed and which might appeal to UK domiciled people with children.

However, I did squeeze in a few short and refreshing mini-surfs, during which I found this, and this, (ignore the preceding advertisement), and this. Reading the last one, it struck me that there is a reluctance to pander for popularity about Clive James's attitude these days (perhaps it was there always and has only become very noticeable recently) that reminds me more and more of Les Murray. Two extraordinarily brilliant independent thinkers (who also happen to be Australian - or is being Australian the single important element that makes them contrarians?) in a largely thoughtless and conformist world.

Oh, and my daughter just sent me this pretty site, which she designed and which might appeal to UK domiciled people with children.

Sunday, 24 February 2013

Magic Eye

Until a few years ago, odd-looking photographs used to appear in the Melbourne Sunday paper we bought every weekend. They were 'Magic Eye' pictures and, if you wanted to see them properly, you had to do something with your eyes that it wasn't possible to explain - or even to do at will really. It involved relaxing in some odd way and changing your focus from its normal setting. It didn't involve thinking. It wasn't something you could follow a set of instructions to achieve.

It seems to me that writing is a bit like that - and therefore trying to teach it as a craft skill may be a bit of a waste of time. In my experience, the happiest moments of writing happen at exactly the moment when all the normal bits of your mind start letting go and functioning outside their usual parameters. It's not something you can make a decision to achieve. Rather, it's something you actually have to forget you want to do.

Which I suppose means that creative writing courses may be useful, provided they force people to write so much, so fast and so furiously that their thoughts transcend self-conscious anxieties and the usual frantic scrabbling and reach a point that is beyond dogged concentration, beyond the stage where a sense of control or order - or really almost anything conscious - remains in the students' minds.

At that point, in a shift as mystifying as the moment when the hidden world contained within a Magic Eye picture suddenly leaps out at the viewer, students may find, inexplicably, that their writing flows easily. In both processes, the trick is not mastery of oneself but the ability to lose control and let go. In both, the experience is a very odd one - a sensation that goes against almost everything we've ever been taught to do.

It seems to me that writing is a bit like that - and therefore trying to teach it as a craft skill may be a bit of a waste of time. In my experience, the happiest moments of writing happen at exactly the moment when all the normal bits of your mind start letting go and functioning outside their usual parameters. It's not something you can make a decision to achieve. Rather, it's something you actually have to forget you want to do.

Which I suppose means that creative writing courses may be useful, provided they force people to write so much, so fast and so furiously that their thoughts transcend self-conscious anxieties and the usual frantic scrabbling and reach a point that is beyond dogged concentration, beyond the stage where a sense of control or order - or really almost anything conscious - remains in the students' minds.

At that point, in a shift as mystifying as the moment when the hidden world contained within a Magic Eye picture suddenly leaps out at the viewer, students may find, inexplicably, that their writing flows easily. In both processes, the trick is not mastery of oneself but the ability to lose control and let go. In both, the experience is a very odd one - a sensation that goes against almost everything we've ever been taught to do.

Wednesday, 20 February 2013

Looking at History

Today I would like to salute a historian called RJ Unstead. Everything I know about history (admittedly not a great deal) I know only thanks to him. His were the works that introduced me to the subject and also the only ones that ever captured any of my attention. Even now, whenever I need to know anything about the past, I turn first to him. Thus, when the news broke recently about the discovery of Richard III's remains under a carpark and I thought, 'Now who was Richard III and when exactly did he live', it was Unstead I got down from the shelf.

Unstead wrote a series called Looking at History and I encountered all four volumes when I was at primary school. I was thrilled also to find the whole set, bound together, on the shelves of the late lamented Chelsea Bookshop, a narrow, dark place on the King's Road in Chelsea, run by two somewhat ill-tempered ladies, who seemed elderly to me at the time but were probably merely middle-aged in fact.

Most of the spare time that I did not spend in the children's section of the Chelsea Public Library, (not, as now, housed in the old town hall but diagonally across the road and around the corner from there), was spent in the Chelsea Bookshop until, in the mid sixties, it was swept away in the great change that rid the King's Road of all businesses not devoted to the sale of glittery dresses and other tat, (luckily, just about exactly at that same moment my interest switched from reading to glittery dresses; luckily for me, that is, although possibly not so great for the ill-tempered ladies).

Anyway, I saved up my pocket money and bought the complete Looking at History and I still have it:

I still love it as well. It explains right at the beginning that what it will provide is everything about Britain 'from Cavemen to the Present Day', (the 'Present Day' referred to was actually 1963, but who wants to hear about anything that's happened since then really - it's mostly depressing, after all).

While Britain is a bit of a stretch for what is really a book about England's history, what you get is an introduction to all the major events of English history, with the odd nod to the existence of Scotland and no mention at all of Ireland or Wales - or such brief ones that I missed them. Leaving aside that bias, (and I do realise that there will be those who just can't do that), the book is remarkably even-handed. For instance, when explaining about the Norman invasion, Unstead simply states this:

Later he does mention that 'the Saxons hated the Normans', but there is no taking sides about whether they were justified in doing so.

His approach is similar when he introduces Cromwell, (and younger readers please note - gay for Unstead merely meant blithe):

He's certainly more balanced than this fellow:

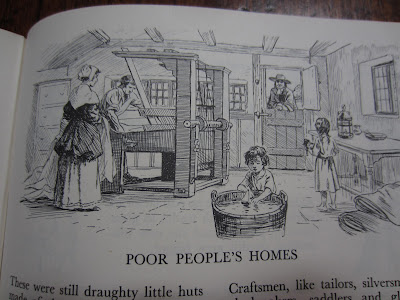

What makes the book really interesting though is the way that events are really only a kind of skeleton that gives the thing structure. The bulk of the text is concerned not with battles or kings or parliament but with the details of daily life for ordinary people. It includes sections called 'Happenings' but they form only a small part of the whole. Around them, recurring sections detail all manner of other aspects of existence in the past.

With the help of numerous illustrations, mostly taken from scholarly works or from the collections of the British Museum, the Public Record Office, the Victoria and Albert Museum and many other smaller enterprises, Unstead's work brought the world of the past vividly to life for me - and it still does.

He focusses on the day-to-day things we all share, making it almost impossible for readers not to identify with their predecessors. For instance, he tells us about the food that was eaten at different stages of the nation's history:

and the kinds of uniforms:

and clothes:

that people wore.

He shows us how people's houses were furnished:

and how the streets looked:

He tells us about how people got about:

and also about children's activities:

Excitingly (my cousin and I must clearly have been shaping up to be future tabloid readers, as we would turn to these with guilty salacity, if that's the word - and, if we were anything to go by, Steerforth need not worry about the harmful effects a rather grim old seafront slot machine might have had upon his younger son), he tells us about punishments:

He also tells us about entertainments:

and the insides of houses:

Despite things being dealt with very briefly - this was after all a text for early primary school - Unstead still managed tremendous clarity, as can be seen from this brief explanation of the wireless:

Reading the book now, I am surprised to find that it has not dated in terms of its attitudes. While it is clearly unforgivable that Unstead makes no mention of England's treatment of the Irish - or indeed any hint at all that not all members of the union might be equally happy (and, of course, he doesn't even contemplate for a moment the idea of dealing with this thing called world history which seems to be the latest fashion), I cannot see any sign of jingoism or racism or any of those things that we are sometimes led to believe were bred in the bone of our forebears and need to be eradicated from our consciousnesses now. Certainly the book is bafflingly short on reasons for the start of World War I:

but then again I've never read anyone who has managed to show how the outbreak of that war did make any kind of proper rational sense.

In any case, despite its minor flaws, the work's great strength for me was that it captured my imagination in a way that barely any history book has done since (the one exception I can think of is JB Bury's History of Greece). It introduced me to the idea that history was about people who ate and drank and played and wore clothes, just as I did, thus instilling - in me at least - a kind of fellow feeling with the past.

It left indelible memories too, which isn't bad for something I was introduced to at the age of six. For instance, when I went to Lavenham three or four years ago and clapped eyes on the Wool Hall, it was almost like stepping through the back of a cupboard into Narnia, for I had been carrying around in my mind the image of that exact building, ever since I'd seen it in Looking at History several decades earlier:

What is more, through an odd working of nostalgia - for the book, and the age I was, and the coziness of the classroom in which I first encountered it - I now find, coming back to England by plane, that I experience a kind of secondary nostalgia for the country itself, as I look down and see faint traces in pasture that, RJ Unstead taught me to recognise, correspond to the old feudal land divisions:

The book ends with a series of questions which suggest to me that it is very difficult to imagine any sort of change except the one you have already experienced. Thus, Unstead dwells on faster and faster transport but has no inkling of the developments in communication that are heading his way. He finishes thus:

"Perhaps the Age of Coal and Iron is already over and we have entered a new Age of Plastics and Atomic Power, in which men will no longer labour to put brick upon brick, or to dig for fuel in coalmines. We have certainly entered an age of speed and science, in which ways of life will change more swiftly than in the past.

Will life become easy and pleasant, or dangerous, yet dull? What do you think?"

Quite a good question, to which I do not have the answer.

What do you think?

Unstead wrote a series called Looking at History and I encountered all four volumes when I was at primary school. I was thrilled also to find the whole set, bound together, on the shelves of the late lamented Chelsea Bookshop, a narrow, dark place on the King's Road in Chelsea, run by two somewhat ill-tempered ladies, who seemed elderly to me at the time but were probably merely middle-aged in fact.

Most of the spare time that I did not spend in the children's section of the Chelsea Public Library, (not, as now, housed in the old town hall but diagonally across the road and around the corner from there), was spent in the Chelsea Bookshop until, in the mid sixties, it was swept away in the great change that rid the King's Road of all businesses not devoted to the sale of glittery dresses and other tat, (luckily, just about exactly at that same moment my interest switched from reading to glittery dresses; luckily for me, that is, although possibly not so great for the ill-tempered ladies).

Anyway, I saved up my pocket money and bought the complete Looking at History and I still have it:

I still love it as well. It explains right at the beginning that what it will provide is everything about Britain 'from Cavemen to the Present Day', (the 'Present Day' referred to was actually 1963, but who wants to hear about anything that's happened since then really - it's mostly depressing, after all).

While Britain is a bit of a stretch for what is really a book about England's history, what you get is an introduction to all the major events of English history, with the odd nod to the existence of Scotland and no mention at all of Ireland or Wales - or such brief ones that I missed them. Leaving aside that bias, (and I do realise that there will be those who just can't do that), the book is remarkably even-handed. For instance, when explaining about the Norman invasion, Unstead simply states this:

Later he does mention that 'the Saxons hated the Normans', but there is no taking sides about whether they were justified in doing so.

His approach is similar when he introduces Cromwell, (and younger readers please note - gay for Unstead merely meant blithe):

He's certainly more balanced than this fellow:

What makes the book really interesting though is the way that events are really only a kind of skeleton that gives the thing structure. The bulk of the text is concerned not with battles or kings or parliament but with the details of daily life for ordinary people. It includes sections called 'Happenings' but they form only a small part of the whole. Around them, recurring sections detail all manner of other aspects of existence in the past.

With the help of numerous illustrations, mostly taken from scholarly works or from the collections of the British Museum, the Public Record Office, the Victoria and Albert Museum and many other smaller enterprises, Unstead's work brought the world of the past vividly to life for me - and it still does.

He focusses on the day-to-day things we all share, making it almost impossible for readers not to identify with their predecessors. For instance, he tells us about the food that was eaten at different stages of the nation's history:

and the kinds of uniforms:

and clothes:

that people wore.

He shows us how people's houses were furnished:

and how the streets looked:

He tells us about how people got about:

and also about children's activities:

Excitingly (my cousin and I must clearly have been shaping up to be future tabloid readers, as we would turn to these with guilty salacity, if that's the word - and, if we were anything to go by, Steerforth need not worry about the harmful effects a rather grim old seafront slot machine might have had upon his younger son), he tells us about punishments:

He also tells us about entertainments:

and the insides of houses:

Despite things being dealt with very briefly - this was after all a text for early primary school - Unstead still managed tremendous clarity, as can be seen from this brief explanation of the wireless:

Reading the book now, I am surprised to find that it has not dated in terms of its attitudes. While it is clearly unforgivable that Unstead makes no mention of England's treatment of the Irish - or indeed any hint at all that not all members of the union might be equally happy (and, of course, he doesn't even contemplate for a moment the idea of dealing with this thing called world history which seems to be the latest fashion), I cannot see any sign of jingoism or racism or any of those things that we are sometimes led to believe were bred in the bone of our forebears and need to be eradicated from our consciousnesses now. Certainly the book is bafflingly short on reasons for the start of World War I:

but then again I've never read anyone who has managed to show how the outbreak of that war did make any kind of proper rational sense.

In any case, despite its minor flaws, the work's great strength for me was that it captured my imagination in a way that barely any history book has done since (the one exception I can think of is JB Bury's History of Greece). It introduced me to the idea that history was about people who ate and drank and played and wore clothes, just as I did, thus instilling - in me at least - a kind of fellow feeling with the past.

It left indelible memories too, which isn't bad for something I was introduced to at the age of six. For instance, when I went to Lavenham three or four years ago and clapped eyes on the Wool Hall, it was almost like stepping through the back of a cupboard into Narnia, for I had been carrying around in my mind the image of that exact building, ever since I'd seen it in Looking at History several decades earlier:

What is more, through an odd working of nostalgia - for the book, and the age I was, and the coziness of the classroom in which I first encountered it - I now find, coming back to England by plane, that I experience a kind of secondary nostalgia for the country itself, as I look down and see faint traces in pasture that, RJ Unstead taught me to recognise, correspond to the old feudal land divisions:

The book ends with a series of questions which suggest to me that it is very difficult to imagine any sort of change except the one you have already experienced. Thus, Unstead dwells on faster and faster transport but has no inkling of the developments in communication that are heading his way. He finishes thus:

"Perhaps the Age of Coal and Iron is already over and we have entered a new Age of Plastics and Atomic Power, in which men will no longer labour to put brick upon brick, or to dig for fuel in coalmines. We have certainly entered an age of speed and science, in which ways of life will change more swiftly than in the past.

Will life become easy and pleasant, or dangerous, yet dull? What do you think?"

Quite a good question, to which I do not have the answer.

What do you think?

Monday, 18 February 2013

Freecycle - It's No Longer Coming on Christmas

Now that the great feast of the Christian calendar is well and truly over, someone has had a change of heart:

"I have the following CDs by Christian artists. Happy for them to go as one or two lots. All in very good condition.

Let me know when you can pick them up in your response please.

Christian City Church – Fresh As

Christian City Church – For Your Glory

Christian City Church – Presence 2005

Christian City Church – Great Is Our God

Christian City Church – Here We Go

Christian City Church – Worship

Hillsong – For This Cause

Hillsong – By Your Side

Michael O Martian – The Race

Seventy cassettes narrated from the New Living Bible Translation.

New International Version Couples' Devotional Bible – Perfect for engaged and newly married couples, comes in soft leather bound zip-up cover with the footprints on the sand story embossed into the leather on front cover. As new - and truly beautiful, would make a wonderful gift, for a couple."

Meanwhile, another Freecycler has quite different things on their mind - although precisely what they are is hard to imagine:

"Wanted: A bucket with a lid and Anne of Green Gables"

"I have the following CDs by Christian artists. Happy for them to go as one or two lots. All in very good condition.

Let me know when you can pick them up in your response please.

Christian City Church – Fresh As

Christian City Church – For Your Glory

Christian City Church – Presence 2005

Christian City Church – Great Is Our God

Christian City Church – Here We Go

Christian City Church – Worship

Hillsong – For This Cause

Hillsong – By Your Side

Michael O Martian – The Race

Seventy cassettes narrated from the New Living Bible Translation.

New International Version Couples' Devotional Bible – Perfect for engaged and newly married couples, comes in soft leather bound zip-up cover with the footprints on the sand story embossed into the leather on front cover. As new - and truly beautiful, would make a wonderful gift, for a couple."

Meanwhile, another Freecycler has quite different things on their mind - although precisely what they are is hard to imagine:

"Wanted: A bucket with a lid and Anne of Green Gables"

Saturday, 16 February 2013

Things I Discovered on the Internet February 3 to 16

This brought tears to my eyes - but then the very mention of Auden moves me, mainly because I love him so much and also a little bit because of the story my brother told me, which his tutor at Oxford, a contemporary of Auden's, told him, about how during their final exams my brother's tutor and Auden were placed at neighbouring tables in the examination hall and, while my brother's tutor scribbled away, Auden sat beside him, writing haltingly, as if forcing his pen through sand or snowdrifts, tears streaming down his face.

And, having been reminded of Auden, I disappeared down one of the Internet's myriad (possibly infinite?) rabbit holes and came back with this, which includes a very good summary of many of the things that make Auden's poetry great and an elucidation of his reticent (hurray -I was so relieved when I read the other day that since the 1990s the power of the Evangelical movement has been waning) Christianity, which aligns entirely with my beliefs, although I lack the articulacy to explain them so well:

"...accordingly we are to take one thing and one thing only seriously, our eternal duty to be happy, and to that all considerations of pleasure and pain are subordinate. Thou shalt love God and thy neighbour and Thou shall be happy mean the same thing":

This told me so much I did not know about another marvellous poet - not least this incredible anecdote:

"Life on the dairy farm was unforgiving, sometimes comically so. One of the few treasured family heirlooms, a watch handed down from Murray’s grandmother to his father, was swallowed whole by a cow."

This, via The Essayist tumblr, introduced me to John Jeremiah Sullivan who is a dazzling writer (his work is beautifully analysed by James Wood here) I have now bought a book of his collected essays and discovered that he can write about anything and be interesting, but, even if he weren't interesting, the subject of the piece I found on The Essayist, (reality TV), is - at least to me - interesting in itself, despite the article being several years old.

The reason I find it interesting is my suspicion that, quite unawares, we are all being changed by reality TV, mainly because of the way in which it establishes celebrity as a goal to be attained on its own, where once celebrity was merely a by-product of an individual's achievement in something other than fame itself.

This new phenomenon is altering expectations and behaviour, I fear. We think about ourselves differently since we have been shown how everything, however mundane, can be framed as performance (and don't get me started on Facebook in this context). Every gesture, every shopping expedition, every walk in the country is potentially a spectacle, recorded by an unseen camera, synthesised into narrative with the help of an understanding voiceover. In this way of seeing, a life that is not watchable - for instance, a life spent reading or thinking, a life lacking hectic human interaction and, ideally, conflict - may become a life that is not worthy of being led.

And, having been reminded of Auden, I disappeared down one of the Internet's myriad (possibly infinite?) rabbit holes and came back with this, which includes a very good summary of many of the things that make Auden's poetry great and an elucidation of his reticent (hurray -I was so relieved when I read the other day that since the 1990s the power of the Evangelical movement has been waning) Christianity, which aligns entirely with my beliefs, although I lack the articulacy to explain them so well:

"...accordingly we are to take one thing and one thing only seriously, our eternal duty to be happy, and to that all considerations of pleasure and pain are subordinate. Thou shalt love God and thy neighbour and Thou shall be happy mean the same thing":

This told me so much I did not know about another marvellous poet - not least this incredible anecdote:

"Life on the dairy farm was unforgiving, sometimes comically so. One of the few treasured family heirlooms, a watch handed down from Murray’s grandmother to his father, was swallowed whole by a cow."

This, via The Essayist tumblr, introduced me to John Jeremiah Sullivan who is a dazzling writer (his work is beautifully analysed by James Wood here) I have now bought a book of his collected essays and discovered that he can write about anything and be interesting, but, even if he weren't interesting, the subject of the piece I found on The Essayist, (reality TV), is - at least to me - interesting in itself, despite the article being several years old.

The reason I find it interesting is my suspicion that, quite unawares, we are all being changed by reality TV, mainly because of the way in which it establishes celebrity as a goal to be attained on its own, where once celebrity was merely a by-product of an individual's achievement in something other than fame itself.

This new phenomenon is altering expectations and behaviour, I fear. We think about ourselves differently since we have been shown how everything, however mundane, can be framed as performance (and don't get me started on Facebook in this context). Every gesture, every shopping expedition, every walk in the country is potentially a spectacle, recorded by an unseen camera, synthesised into narrative with the help of an understanding voiceover. In this way of seeing, a life that is not watchable - for instance, a life spent reading or thinking, a life lacking hectic human interaction and, ideally, conflict - may become a life that is not worthy of being led.

Wednesday, 13 February 2013

Community Service

At this time of year, the decision to plant not one zucchini (courgette) plant, not two, but, on the grounds that one or more might turn up their toes, three zucchini plants way back in October always comes back to haunt me. Why do I never accept that there is really never going to be a shortage of zucchinis, even with one plant? Why do I never remember that they very rarely turn up their toes and more than one plant will always produce an amount that makes the word glut an understatement?

Assuming that I am not the only Canberran foolish enough to produce for myself, year after year, an overabundance of long, green, fairly tasteless vegetables, I have decided to provide to others in the same position a recipe that has become my greatest ally in the face of this absurd and entirely avoidable annual problem.

The recipe in question is for something called a Zucchini slice. It isn't the most wildly exciting thing I've ever eaten but it can be frozen, and sometimes in the depths of winter, when you can't be bothered to cook anything that involves chopping et cetera, it can be removed from the freezer, heated in the oven, and produced miraculously, together with a salad of whatever you can find in the vegetable garden (there is always, always rocket). I have to admit that no-one in my household has ever said, 'Oooh goody, zucchini slice' or 'Oh, couldn't we have zucchini slice tonight'; on the other hand, there has never been any left at the end of a meal:

Heat oven to 170C

Beat 5 eggs, add a cup of self-raising flour and beat until smooth, add in 375g grated zucchini, a chopped onion, 200g chopped bacon or smoked ham, 1 cup grated cheddar, 1/4 cup veg oil. Combine, put into a baking dish and cook until golden. Eat or freeze and eat later.

I do also possess a recipe or two for zucchini cake and zucchini muffins, should anyone want them. If I'm absolutely honest, I actually own a copy of a publication called The Squash Cookbook which is almost entirely devoted to what to do with vegetable marrows of various kinds. Most of the recipes are very fiddly though, (who really wants to spend their time stuffing baby courgettes when the sun is shining?) whereas the one above is a trusty thing that involves no stuffing and cannot be stuffed up, unless you forget it's in the oven.

If anyone's got too much basil, incidentally, I've recently discovered that home-made pesto is just as delicious - or possibly more delicious - if you don't toast the pine nuts. Apparently they never do in Liguria (and the pesto I had there was great).

Assuming that I am not the only Canberran foolish enough to produce for myself, year after year, an overabundance of long, green, fairly tasteless vegetables, I have decided to provide to others in the same position a recipe that has become my greatest ally in the face of this absurd and entirely avoidable annual problem.

The recipe in question is for something called a Zucchini slice. It isn't the most wildly exciting thing I've ever eaten but it can be frozen, and sometimes in the depths of winter, when you can't be bothered to cook anything that involves chopping et cetera, it can be removed from the freezer, heated in the oven, and produced miraculously, together with a salad of whatever you can find in the vegetable garden (there is always, always rocket). I have to admit that no-one in my household has ever said, 'Oooh goody, zucchini slice' or 'Oh, couldn't we have zucchini slice tonight'; on the other hand, there has never been any left at the end of a meal:

Heat oven to 170C

Beat 5 eggs, add a cup of self-raising flour and beat until smooth, add in 375g grated zucchini, a chopped onion, 200g chopped bacon or smoked ham, 1 cup grated cheddar, 1/4 cup veg oil. Combine, put into a baking dish and cook until golden. Eat or freeze and eat later.

I do also possess a recipe or two for zucchini cake and zucchini muffins, should anyone want them. If I'm absolutely honest, I actually own a copy of a publication called The Squash Cookbook which is almost entirely devoted to what to do with vegetable marrows of various kinds. Most of the recipes are very fiddly though, (who really wants to spend their time stuffing baby courgettes when the sun is shining?) whereas the one above is a trusty thing that involves no stuffing and cannot be stuffed up, unless you forget it's in the oven.

If anyone's got too much basil, incidentally, I've recently discovered that home-made pesto is just as delicious - or possibly more delicious - if you don't toast the pine nuts. Apparently they never do in Liguria (and the pesto I had there was great).

Tuesday, 12 February 2013

How Now Thou Lovely Plough

I love learning foreign languages, but I've gone on in detail about that before. At the time I also mentioned my curiosity about the loss of the 'thou' form in English. Why did we lose it, when did we lose it and does it mean we're all ice-cold swine?

Anyway, I should also have mentioned, while on that particular subject, that one of the things I find adorable about the fiendishly hard Hungarian language is the fact that, as well as having the 'you' and 'thou' forms familiar to anyone who's had a go at any of the Germanic, Slavic or Romance languages, it also has a third utterly unfathomable - to me at least - mode of address that is either more or less haughty than the other two (I've never been able to make out where it really fits in in the complex world of linguistic efforts to express the subtleties of human relationships).

Furthermore, Hungarians, already in possession of an extra nuance in their interchanges, (and two different verb declensions, depending upon whether the object of their sentence is vague - 'a', 'some', 'several' - or definite - 'the'), also have a verb form reserved specifically for activities that go on between a first person singular - 'I' - subject and a second person singular (or plural [ideal for orgies]) - 'thou' - object. Thus, there is 'I see him' and 'I see you' and 'he sees thou', but, as well, in the phrase 'I see thou', a special iteration of the verb is used to convey the exclusively intimate relationship that exists between an 'I' and a 'thou'.

Such nuance in a language's grammar strikes me as both sophisticated and sensitive. My mother tongue seems a rather primitive tool by comparison. Remembering how as a small child in primary school I baffled my teacher - (no, no, not lovely Miss Monck Mason, she would have understood immediately - it was that horrid Miss Pickard) - by writing a story - (at the school that I went to virtually all we ever did was write stories) - about a character called 'pudding hat' who led an uprising of the common nouns, demanding the same rights as proper nouns to have initial capital letters - (of course, 'pudding' should have moved to Germany I realised when I started learning that language decades later) - I wonder now whether it is in fact English verbs, rather than nouns, that should be revolting. Rise up, 'doing words', demand equality with your more subtle Hungarian chums.

Anyway, I should also have mentioned, while on that particular subject, that one of the things I find adorable about the fiendishly hard Hungarian language is the fact that, as well as having the 'you' and 'thou' forms familiar to anyone who's had a go at any of the Germanic, Slavic or Romance languages, it also has a third utterly unfathomable - to me at least - mode of address that is either more or less haughty than the other two (I've never been able to make out where it really fits in in the complex world of linguistic efforts to express the subtleties of human relationships).

Furthermore, Hungarians, already in possession of an extra nuance in their interchanges, (and two different verb declensions, depending upon whether the object of their sentence is vague - 'a', 'some', 'several' - or definite - 'the'), also have a verb form reserved specifically for activities that go on between a first person singular - 'I' - subject and a second person singular (or plural [ideal for orgies]) - 'thou' - object. Thus, there is 'I see him' and 'I see you' and 'he sees thou', but, as well, in the phrase 'I see thou', a special iteration of the verb is used to convey the exclusively intimate relationship that exists between an 'I' and a 'thou'.

Such nuance in a language's grammar strikes me as both sophisticated and sensitive. My mother tongue seems a rather primitive tool by comparison. Remembering how as a small child in primary school I baffled my teacher - (no, no, not lovely Miss Monck Mason, she would have understood immediately - it was that horrid Miss Pickard) - by writing a story - (at the school that I went to virtually all we ever did was write stories) - about a character called 'pudding hat' who led an uprising of the common nouns, demanding the same rights as proper nouns to have initial capital letters - (of course, 'pudding' should have moved to Germany I realised when I started learning that language decades later) - I wonder now whether it is in fact English verbs, rather than nouns, that should be revolting. Rise up, 'doing words', demand equality with your more subtle Hungarian chums.

Monday, 11 February 2013

Sydney Vernacular

I've been dealing with Sydney people lately. Sydney is different. Well, anywhere is different, when you live in Canberra. But there is a ridiculous kind of swagger adopted by a certain kind of young wheeler dealer in Sydney (estate agents particularly). One of the annoying little traits I've noticed as I've listened to them and communicated with them over the internet is the new habit of saying not, 'Send me an email', but 'Shoot me an email'. Why? Does it sound more exciting? Did they pick it up from some hipster movie? I know it doesn't matter; it's just that it jars.

Thursday, 7 February 2013

Bijou Batts and Dior Kaffies

My youngest daughter and I were walking down Macleay Street in Sydney the other night, looking for the restaurant where we were to meet my brother, when a couple came out of a bar, arm in arm. As they strolled along beside us, they began a high-volume conversation, which I couldn't help suspecting was being conducted for our benefit.

'Do you remember the shop where that lovely trans-gender girl used to sell frocks, down there on the left?' began the male of the couple.

'She's still there,' replied the woman, who, her voice revealed, was also a man. 'I bought a lovely chiffon skirt by Dior from her just the other day.'

'Oooh, have you got Dior couture in your wardrobe? I've only got vintage Dior.'

'My dear, if you want vintage, you should see my Balenciaga jacket: it's practically seamless - just a single piece of fabric; what a cutter!'

We tried to ignore this megaphone interchange, concentrating instead on the building numbers, searching for the one my brother had given us.

'There it is,' I cried, when I finally spotted it. The woman of the couple glanced over at the establishment I'd pointed out.

'Do you remember when that place used to be fashionable?' she asked and looked straight at me. Her expression suggested she'd trodden in something very unpleasant.

'I am so sick of being surrounded by mono-genders', she said, with a toss of her pony tail and then the two of them sauntered off into the night.

'Do you remember the shop where that lovely trans-gender girl used to sell frocks, down there on the left?' began the male of the couple.

'She's still there,' replied the woman, who, her voice revealed, was also a man. 'I bought a lovely chiffon skirt by Dior from her just the other day.'

'Oooh, have you got Dior couture in your wardrobe? I've only got vintage Dior.'

'My dear, if you want vintage, you should see my Balenciaga jacket: it's practically seamless - just a single piece of fabric; what a cutter!'

We tried to ignore this megaphone interchange, concentrating instead on the building numbers, searching for the one my brother had given us.

'There it is,' I cried, when I finally spotted it. The woman of the couple glanced over at the establishment I'd pointed out.

'Do you remember when that place used to be fashionable?' she asked and looked straight at me. Her expression suggested she'd trodden in something very unpleasant.

'I am so sick of being surrounded by mono-genders', she said, with a toss of her pony tail and then the two of them sauntered off into the night.

Saturday, 2 February 2013

Things I Found on the Web - 26 January to 2 February 2013

My absolute favourite thing, of all the things I read on the web this week was definitely this story about the Russian family who lived in isolation in Siberia. It leaves you with so much to imagine.

I also enjoyed an article about International Art English or IAE, a form of English that is "a unique language" that has "everything to do with English, but is emphatically not English. [It] is oddly pornographic: we know it when we see it." Here is an example of IAE:

"The artist brings the viewer face to face with their own preconceived hierarchy of cultural values and assumptions of artistic worth ... Each mirror imaginatively propels its viewer forward into the seemingly infinite progression of possible reproductions that the artist's practice engenders, whilst simultaneously pulling them backwards in a quest for the 'original' source or referent that underlines Levine's oeuvre."

Here is another article that I also enjoyed on the ludicrous business that is contemporary art. Perhaps my favourite bit in it was this:

"The men at Sotheby’s greased back their longish hair with some sort of unidentifiable shellac. In their well-tailored suits and leather-soled shoes, they looked like patrician vampires."

I was intrigued by an article about a library of unpublished books, which included this wonderfully unprovable assertion from a writer of unpublished books:

“I believe the best novels are in the minds of people who don’t have the time to write them,” Alyce told me, explaining that she had first begun to write Did She Leave Me Any Money? while she was the visual-communications manager for a city agency in Portland. “Faulkner? Hemingway? Their novels aren’t nearly as good as those that could be written if only people had the time to write them.”

I was initially interested by the words of Timothy Donnelly, a poet I'd not heard of before:

"I’m disinclined to let myself think that my poems might appeal to an “establishment,” because that word suggests to me a league of misguided writers struggling to maintain the status quo. Deep down they’re anxious about how boring their work is, or if they’re plainspoken confessional poets, they probably aren’t really poets at all, but just heartfelt expressers in verse, and they will insist that that’s what poetry is, goddammit — and trying to loosen them up and get them to think otherwise can be about as useless as encouraging a bullfrog to fly. You might get them to leap a little, but that’s about it".

Donnelly wrote this, which at first I liked very much and which reminded me of one of the stories in Peter Carey's early short story collection, The Fat Man in History (I can't find my own copy, but I think the story may be called 'Dreams') and then I suddenly decided I didn't like quite as much, but whether that was a result of my own fluctuating ability to respond to poetry and, indeed, other works of art (does anyone else suffer from this - occasional lapses into a bleak kind of dreariness where for some reason nothing much seems any good? A good blast of Beethoven usually shakes me out of it, but it's annoying) or not, I can't tell.

I also enjoyed an article about International Art English or IAE, a form of English that is "a unique language" that has "everything to do with English, but is emphatically not English. [It] is oddly pornographic: we know it when we see it." Here is an example of IAE:

"The artist brings the viewer face to face with their own preconceived hierarchy of cultural values and assumptions of artistic worth ... Each mirror imaginatively propels its viewer forward into the seemingly infinite progression of possible reproductions that the artist's practice engenders, whilst simultaneously pulling them backwards in a quest for the 'original' source or referent that underlines Levine's oeuvre."

Here is another article that I also enjoyed on the ludicrous business that is contemporary art. Perhaps my favourite bit in it was this:

"The men at Sotheby’s greased back their longish hair with some sort of unidentifiable shellac. In their well-tailored suits and leather-soled shoes, they looked like patrician vampires."

I was intrigued by an article about a library of unpublished books, which included this wonderfully unprovable assertion from a writer of unpublished books:

“I believe the best novels are in the minds of people who don’t have the time to write them,” Alyce told me, explaining that she had first begun to write Did She Leave Me Any Money? while she was the visual-communications manager for a city agency in Portland. “Faulkner? Hemingway? Their novels aren’t nearly as good as those that could be written if only people had the time to write them.”

I was initially interested by the words of Timothy Donnelly, a poet I'd not heard of before:

"I’m disinclined to let myself think that my poems might appeal to an “establishment,” because that word suggests to me a league of misguided writers struggling to maintain the status quo. Deep down they’re anxious about how boring their work is, or if they’re plainspoken confessional poets, they probably aren’t really poets at all, but just heartfelt expressers in verse, and they will insist that that’s what poetry is, goddammit — and trying to loosen them up and get them to think otherwise can be about as useless as encouraging a bullfrog to fly. You might get them to leap a little, but that’s about it".

Donnelly wrote this, which at first I liked very much and which reminded me of one of the stories in Peter Carey's early short story collection, The Fat Man in History (I can't find my own copy, but I think the story may be called 'Dreams') and then I suddenly decided I didn't like quite as much, but whether that was a result of my own fluctuating ability to respond to poetry and, indeed, other works of art (does anyone else suffer from this - occasional lapses into a bleak kind of dreariness where for some reason nothing much seems any good? A good blast of Beethoven usually shakes me out of it, but it's annoying) or not, I can't tell.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)