Unstead wrote a series called Looking at History and I encountered all four volumes when I was at primary school. I was thrilled also to find the whole set, bound together, on the shelves of the late lamented Chelsea Bookshop, a narrow, dark place on the King's Road in Chelsea, run by two somewhat ill-tempered ladies, who seemed elderly to me at the time but were probably merely middle-aged in fact.

Most of the spare time that I did not spend in the children's section of the Chelsea Public Library, (not, as now, housed in the old town hall but diagonally across the road and around the corner from there), was spent in the Chelsea Bookshop until, in the mid sixties, it was swept away in the great change that rid the King's Road of all businesses not devoted to the sale of glittery dresses and other tat, (luckily, just about exactly at that same moment my interest switched from reading to glittery dresses; luckily for me, that is, although possibly not so great for the ill-tempered ladies).

Anyway, I saved up my pocket money and bought the complete Looking at History and I still have it:

I still love it as well. It explains right at the beginning that what it will provide is everything about Britain 'from Cavemen to the Present Day', (the 'Present Day' referred to was actually 1963, but who wants to hear about anything that's happened since then really - it's mostly depressing, after all).

While Britain is a bit of a stretch for what is really a book about England's history, what you get is an introduction to all the major events of English history, with the odd nod to the existence of Scotland and no mention at all of Ireland or Wales - or such brief ones that I missed them. Leaving aside that bias, (and I do realise that there will be those who just can't do that), the book is remarkably even-handed. For instance, when explaining about the Norman invasion, Unstead simply states this:

Later he does mention that 'the Saxons hated the Normans', but there is no taking sides about whether they were justified in doing so.

His approach is similar when he introduces Cromwell, (and younger readers please note - gay for Unstead merely meant blithe):

He's certainly more balanced than this fellow:

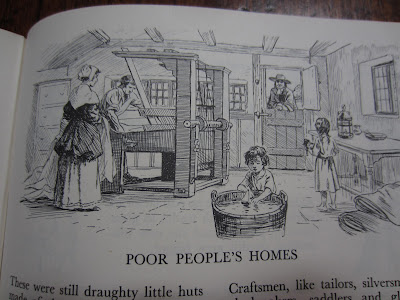

What makes the book really interesting though is the way that events are really only a kind of skeleton that gives the thing structure. The bulk of the text is concerned not with battles or kings or parliament but with the details of daily life for ordinary people. It includes sections called 'Happenings' but they form only a small part of the whole. Around them, recurring sections detail all manner of other aspects of existence in the past.

With the help of numerous illustrations, mostly taken from scholarly works or from the collections of the British Museum, the Public Record Office, the Victoria and Albert Museum and many other smaller enterprises, Unstead's work brought the world of the past vividly to life for me - and it still does.

He focusses on the day-to-day things we all share, making it almost impossible for readers not to identify with their predecessors. For instance, he tells us about the food that was eaten at different stages of the nation's history:

and the kinds of uniforms:

and clothes:

that people wore.

He shows us how people's houses were furnished:

and how the streets looked:

He tells us about how people got about:

and also about children's activities:

Excitingly (my cousin and I must clearly have been shaping up to be future tabloid readers, as we would turn to these with guilty salacity, if that's the word - and, if we were anything to go by, Steerforth need not worry about the harmful effects a rather grim old seafront slot machine might have had upon his younger son), he tells us about punishments:

He also tells us about entertainments:

and the insides of houses:

Despite things being dealt with very briefly - this was after all a text for early primary school - Unstead still managed tremendous clarity, as can be seen from this brief explanation of the wireless:

Reading the book now, I am surprised to find that it has not dated in terms of its attitudes. While it is clearly unforgivable that Unstead makes no mention of England's treatment of the Irish - or indeed any hint at all that not all members of the union might be equally happy (and, of course, he doesn't even contemplate for a moment the idea of dealing with this thing called world history which seems to be the latest fashion), I cannot see any sign of jingoism or racism or any of those things that we are sometimes led to believe were bred in the bone of our forebears and need to be eradicated from our consciousnesses now. Certainly the book is bafflingly short on reasons for the start of World War I:

but then again I've never read anyone who has managed to show how the outbreak of that war did make any kind of proper rational sense.

In any case, despite its minor flaws, the work's great strength for me was that it captured my imagination in a way that barely any history book has done since (the one exception I can think of is JB Bury's History of Greece). It introduced me to the idea that history was about people who ate and drank and played and wore clothes, just as I did, thus instilling - in me at least - a kind of fellow feeling with the past.

It left indelible memories too, which isn't bad for something I was introduced to at the age of six. For instance, when I went to Lavenham three or four years ago and clapped eyes on the Wool Hall, it was almost like stepping through the back of a cupboard into Narnia, for I had been carrying around in my mind the image of that exact building, ever since I'd seen it in Looking at History several decades earlier:

What is more, through an odd working of nostalgia - for the book, and the age I was, and the coziness of the classroom in which I first encountered it - I now find, coming back to England by plane, that I experience a kind of secondary nostalgia for the country itself, as I look down and see faint traces in pasture that, RJ Unstead taught me to recognise, correspond to the old feudal land divisions:

The book ends with a series of questions which suggest to me that it is very difficult to imagine any sort of change except the one you have already experienced. Thus, Unstead dwells on faster and faster transport but has no inkling of the developments in communication that are heading his way. He finishes thus:

"Perhaps the Age of Coal and Iron is already over and we have entered a new Age of Plastics and Atomic Power, in which men will no longer labour to put brick upon brick, or to dig for fuel in coalmines. We have certainly entered an age of speed and science, in which ways of life will change more swiftly than in the past.

Will life become easy and pleasant, or dangerous, yet dull? What do you think?"

Quite a good question, to which I do not have the answer.

What do you think?

I have to agree - marvellous books and very good for adults too, if they want an overview of English history. The details of domestic life are fascinating.

ReplyDeleteWas it the Pan Bookshop in Chelsea? That was run by June Formby, who was a rather formidable woman.

I just looked up the Pan and it appears to be the one at South Kensington tube station (which I hope hasn't closed?) The Chelsea Bookshop was about 5 shops down from the Essoldo Cinema, near Paultons Square. I think it probably closed in 1967 or a year or two after that, along with Laffeaty's, the toy shop opposite, and, of course, the late lamented Thomas Crapper's

DeleteI loved books like these when I was growing up. There was a biography series I read through that was specifically for kids...focusing on their childhoods and how they lived. Formative stuff, meant to inspire.

ReplyDeleteI think it's the clarity of such books that I miss the most, something that got muddied the more I read.

I read a review of a biography about Strindberg recently that claimed Strindberg was the first person to write history from the point of view of ordinary people. I am endlessly curious about what people ate and what they wore and slept on et cetera, much less so about treaties and multi-national trade agreements, which seemed to be what history was full of at school. I suppose it's the difference between political history and social history. Of course, you can't do entirely without the political, but I like it to be no more than a framework within which I learn about day-to-day life as it was. Probably the sign of a trivial mind

DeleteBeing an historian was my trade for almost my whole working life. Any books that provide historical information that captures the imagination of people, children in particular, sit well with me.

ReplyDeleteThis looks beautifully readable. I would take pleasure in going through it. The writing of history is always subjective. When something is obviously propaganda, then I object to it, regardless of how appealing it seems. The chronicles of "great men" are not what I call history.

Social history is not the sign of a trivial mind. People are the stuff of history. How they live and what they think create the world to be written about.

Re Social history versus political history, I am reminded of the thought for the day on the Books Inq blog the other day:

DeletePolitics is the diversion of trivial men who, when they succeed at it, become important in the eyes of more trivial men.

— George Jean Nathan (I looked him up - he was a critic in, I think, the 1920s

RJ Unstead was my great uncle. It warms my heart to hear people speak with such affection of his work. I never knew his books were text books when my father shared them with me, they were just Uncle Bob's books.

ReplyDeleteNow I will look forward to sharing them with my children.

Thank you so much for commenting. I genuinely love his books. Did you know him? I hope he had a happy life and realised how his books were valued.

ReplyDelete