Then I watched the 7.30 Report on ABC television and their reporter, Ben Knight, brought it all to life for me. I hope he gets an award for his reporting. I also hope that that nice chap we see him talk to - the one who calls himself part of 'the silent majority' - ends up okay. I fear the silent majority does not always prevail against the brutal few.

Monday, 31 January 2011

Sunday, 30 January 2011

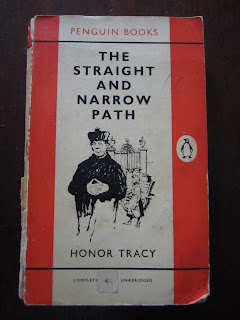

Battered Penguins II

I chose The Volcanoes Above Us because I had a vague idea that its author, Norman Lewis, had had something to do with Elizabeth David. I was wrong, as it happens - that was Norman Douglas. It didn't matter though, because The Volcanoes Above Us turned out to be terrific in its own right.

The novel is narrated by David Williams, whose family owned a coffee plantation, (or 'finca'), in Guatemala, until it was taken from them under an 'agrarian new deal'. When we first meet him, he is sitting in a Mexican jail, determined to reclaim his 'finca'. In order to do this - or merely in order to do something - he agrees, in exchange for his freedom, to join 'General Balboa's Army of Liberation', which, he reads in the paper while sitting in his cell, is going to conduct a revolution in Guatemala: 'The paper did not state this as a possibility but as a definite and pre-arranged fact, as if speaking of an exceptional bullfight or a football match'.

Following the revolution, Williams is sent to Guadaloupe, to take control of the situation there and deal with the local Indians, known as Chillams, a taciturn bunch given to 'praying in loud conversational tones to their gods' and watching new arrivals with 'a kind of furtive hatred.' The Chillams, having had their land returned to them by the former regime, have now had it taken away again, this time by the Universal Coffee Company which, despite its name, is in the business of encouraging tourism, a difficult task given the Chillams' habits: 'If any tourist gets his camera out they spit at him.'

The story that Williams unfolds for us following his arrival in Guadaloupe is one in which the self-belief of Westerners - 'with their big bones, their confidence, their pink flesh, and their earth-inheriting voices' - is confronted by the mysterious, almost medieval (in the sense of non-individualistic) collective spirit of the Chillams, who, according to Elliot Winthrop, the manager of the Company, possess no cultural traditions of their own: 'They don't exist. There aren't any. The only thing they do here when they put on a fiesta is to walk round the streets carrying a black box like a coffin and then get drunk'.

First person narratives can often become oppressive: the reader longs for the freedom of another point of view. In The Volcanoes Above Us, however, this never emerges as a problem. The narrator, Williams, is a witty companion who has an appealing sense of the ridiculous, great descriptive powers and a delightfully sardonic tone. Of General Balboa, leader of the revolution in which Williams participates, he makes this observation, 'His eyes swivelled suddenly in Kranz's direction and I was reminded of the quick sideways scramble of small, black crabs.' Of a rather dubious German who is involved in the government, he says: 'He was brisk, light-hearted, and exuding charm in the same way and for the same purpose as an octopus squirts ink.'

Williams's account of his activities with Balboa's Army of Liberation's is also full of absurd details: '...we were given ... American war-surplus uniforms all made to fit the same fat man with a dwarf's legs ... Discontent developed among the troops when it was discovered that the bulk of the rations consisted of macaroni letters of the alphabet ...' These touches only serve to make the single moment of true horror he encounters during the conflict more vivid and intense. In the passage in which he describes that incident, all trace of humour is stripped away and we are faced with unadorned reality. Although afterwards Williams recovers his original jaunty tone, he admits that 'this sudden contact with the basic facts of war had struck deep into my being and a great number of horrific details of the slaughter which I had contrived to forget in my waking hours were nightly displayed to me in ... recurrent dreams.'

It is this - the human habit of self-delusion in the face of reality, the endless contriving to forget - that is the central theme of the novel (alongside the obvious one of colonialism). Each of the main characters is engaged in a more or less successful attempt to escape the world as it is. Hernandez, a journalist acquaintance of Williams, uses movies for this purpose: 'He had organized his life to give himself the maximum time enjoying what the cinema had to show him of the world ... When the cinemas closed at night he went and sat in a soda-fountain over a milk-shake until that closed too, and then he went to bed. This was his life, and he had created of it a reality of his own ...'

Elliot Winthrop, manager of the Company, although he does 'not bother with novels', is equally interested in fictional alternatives to the here and now. He is entranced by the effects produced by his state of the art gramophone, on which he plays and replays a recording of 'a railway engine starting off, accelerating, travelling at full speed, coming to a standstill ..."It's just as if it was in this room, isn't it"', Elliot exclaims to the narrator, '"I mean to say you have a complete illusion of reality."' Elliot, in fact, is dedicated to the creation of illusions not just for himself but for a wider public. His professional life is entirely devoted to a transformation of the way things are: '"We're building a complete typical Indian village right from the word go."' he explains to Williams. '"What happened to the original Indian village?" I asked ... "We tore it down. There's a difference between a place being picturesque and being a plain eyesore."'

Unfortunately for the Company, the reality that is represented by the Chillams is rather more robust than Elliot realises. As it turns out, he is mistaken about this puzzling race - they do, in fact, have a strong, although incomprehensible, tradition. By the time this becomes apparent, of course, it is already too late to do anything about it: the Chillams are rousing themselves, observed by Williams: 'a white creeping advance of human lava [moving] towards the centre of Guadaloupe', 'moving not so much as individuals but as a gigantic hollow muscle contracting slowly', 'flowing steadily across the bottom of the Alameda - over the central flower beds, across the wide, mosaic pathway, filling the roadway and streaming through more flower beds and shrubberies ...as slow and deliberate as the lazy advance of rollers seen from afar off up a wide beach ... like a termite army [that] would take the shortest route to their objective,' (which seems to be revenge for the smashing of their mysterious black box and the consequent revelation of its contents).

The novel reaches a climax with the ensuing destruction by the Chillams of the Company's project. Following this event, Williams leaves Guatemala, with little idea of what his life holds now. Just as the Company's plans have evaporated, his central illusion - the quest for the return of the family 'finca' - has also gone. Looking down from the plane at 'the veined and crumpled earth', he comforts himself with the realisation that 'I wasn't alone in my capacity for self-deception'. As the book closes he tells us, 'I was optimistic. The kindly fog of illusion was closing in again.'

The Volcanoes Above Us is extremely entertaining, but it also has resonance and depth. In this novel at least Lewis achieved a great feat, creating a book that has an utterly serious central core wrapped in 'the kindly fog' of humour. I highly recommend it.

Friday, 28 January 2011

What Is It Called?

There must be a word for it - that thing where you sit down at the computer and open up your email, to try to find the one you have to answer in order to be able to pay your electricity bill on-line. And there in your inbox is a message from a friend and there's a link in it to You Tube and you look at what they've sent you and you like it and you wonder if there's more like that and then you want to read about the person who made the clip and whether you can buy their stuff and, if so, where. And then you notice an interesting review about them in a magazine that actually turns out to have quite a few interesting articles and one of them leads you to a discussion of the latest work by a writer you like. And, finally, you look at your watch and realise that an hour and a half's gone by and you can't think what you're doing, sitting here, wasting time. And so you close down the computer and wander off to get on with things. And then, as you start your new task, you remember what it was you wanted.

And so you sit down at the computer and open up your email, to try to find the one you have to answer in order to be able to pay your electricity on-line. And there in your inbox is a message from a friend and there's a link to an article and .....

There must be a word for it - fornetfulness is all I can come up with. Someone must be able to think of something better - or find it on the internet. By the time they do, of course, I won't be able to see it, as my electricity will have been cut off, because each time I go to the computer and open up my email to try to find the one I have to answer in order to be able to pay my electricity on-line - well, you know the rest.

And so you sit down at the computer and open up your email, to try to find the one you have to answer in order to be able to pay your electricity on-line. And there in your inbox is a message from a friend and there's a link to an article and .....

There must be a word for it - fornetfulness is all I can come up with. Someone must be able to think of something better - or find it on the internet. By the time they do, of course, I won't be able to see it, as my electricity will have been cut off, because each time I go to the computer and open up my email to try to find the one I have to answer in order to be able to pay my electricity on-line - well, you know the rest.

Thursday, 27 January 2011

Sofia Coppola's Somewhere

Somewhere tells the story (if it can be called that - very little actually happens in the film) of a man who seems to have stumbled into the role of a Hollywood movie star - and indeed appears to be stumbling blindly through his life.

We first clap eyes on him about ten minutes into the movie, emerging from a car we have just seen him drive around and around - and around and around and around and, yes, once again, around - a race track (the film is littered with similar lingering shots - people have compared them to the work of Antonioni, but they recalled to me very dim and distant memories of Jean Luc Godard films [which I saw thanks to the marvellous Colin Crisp, who inaugurated a French cinema course in the French department at Australian National University, before being whisked away to Queensland to become a professor of cinema studies there - he was a really tremendous and entertaining teacher]).

Anyway, the man driving the car, whose name is Johnnie Marko, appears on the far side of the vehicle, revealing himself slowly, moving dazedly, almost as if he is asleep. He takes two steps forward and then stands before us for a moment, looking off to the right, into a distance that is hidden from us. Through his posture alone, he manages to convey a weary disappointment, a stranded boredom, a sense that he is missing something.

Subsequent events appear to bear this out. We watch as he staggers on through various scenes, some more startling than others - he falls asleep while blonde twins pole-dance at the end of his bed, he falls downstairs drunk and fractures his arm, he passes out shortly after flopping into bed with a woman he has just met (before actually doing anything very much with her). Most of his time though is spent alone, indoors. During these periods of solitariness, he appears to have no clue about how to spend his time. As far as we can tell, he possesses no inner resources and has no clear ambition. He just sits on his own, drinking beer from a bottle and smoking, staring into space, like a child waiting to be told what to do next.

And from time to time he is, in fact, given instructions - and, to give him his due, he carries them out dutifully, fronting up for publicity events, ferrying his daughter to skating and, hilariously, allowing a full cast of his skull to be made for use as part of some future movie's special effects. This last activity involves his entire head being enveloped in a thick white goo, which has two holes made in it for him to breathe through. In a shot that does not move except to draw slowly closer to its subject, we watch as he sits patiently, docilely, submitting to this indignity without complaint.

And then his daughter - who has already won our hearts in a poignant scene in which she practises her ice dancing routine with a slightly clumsy seriousness (made all the more touching because of the way it echoes the jerks and grinds of the earlier, sleep-inducing pole dancers) - is thrust upon him for an extended stay. Like Saffy in Absolutely Fabulous, she turns out to have more of a grasp on reality than her parent. She is active and engaged. She is interested in testing herself and trying out new things. She cooks meals, rather than ordering room service. While her father lolls idly on the edge of an indoor pool, she dashes back and forth through the water. When there is nothing to do, she pulls out her sudoku book and diverts her mind. She does not just wait for things to happen to her. She does not submit to boredom.

The days pass. The pair go to Italy for a TV awards ceremony. They return. Their car breaks down and they have to call a mechanic. They lie by the pool of the hotel where Johnnie lives. They go to Las Vegas. The daughter leaves for summer camp. The film ends. Nothing dramatic occurs. There is no sparkly Hollywood epiphany. All the same, we realise that something has happened, although it is nothing spectacular. The daughter has coaxed her father out from behind the walls of the hotel into the sunlight for a brief time. In her company, he has become dimly aware that he is not just a mote of dust drifting through time and space. What will come of this vague step towards understanding we cannot tell. There is no sense at the end of the film that a great redemption has taken place. He may not yet be ready to be master of his own destiny. All we can say is that, whereas at the beginning of the movie he emerged from his car after driving around and around in circles, in the closing scene, looking almost purposeful, he emerges from it after driving in a straight line.

Which is not to suggest that the film is pointless. While it is pretty uneventful and could not be said to move at breakneck speed, it is intriguing. Although some critics have argued that the main character is not only fairly unsympathetic, but also represents a tiny privileged elite and therefore has nothing to tell us, I disagree. Johnnie is certainly infuriating - has he never heard of reading a book (or even a newspaper or, indeed, an article on the internet - there is no sign that he has ever come across a computer) - but the irritating aspects of his personality are also the ones that connect him to the rest of the population. It is not only film stars who have been duped into believing that the meaning of life is to be found in material objects and distracted hedonism, in vivid sensation and high-speed cars. The irony is that Johnnie is part of the system of myth-making that has helped create the false assumptions that have led him to his current emotional dead end. In a similar irony, the film, while set in Hollywood and the shallow outposts of its empire, is itself a thoughtful alternative to the dangerous myths that Hollywood - with Johnnie's help - creates.

We first clap eyes on him about ten minutes into the movie, emerging from a car we have just seen him drive around and around - and around and around and around and, yes, once again, around - a race track (the film is littered with similar lingering shots - people have compared them to the work of Antonioni, but they recalled to me very dim and distant memories of Jean Luc Godard films [which I saw thanks to the marvellous Colin Crisp, who inaugurated a French cinema course in the French department at Australian National University, before being whisked away to Queensland to become a professor of cinema studies there - he was a really tremendous and entertaining teacher]).

Anyway, the man driving the car, whose name is Johnnie Marko, appears on the far side of the vehicle, revealing himself slowly, moving dazedly, almost as if he is asleep. He takes two steps forward and then stands before us for a moment, looking off to the right, into a distance that is hidden from us. Through his posture alone, he manages to convey a weary disappointment, a stranded boredom, a sense that he is missing something.

Subsequent events appear to bear this out. We watch as he staggers on through various scenes, some more startling than others - he falls asleep while blonde twins pole-dance at the end of his bed, he falls downstairs drunk and fractures his arm, he passes out shortly after flopping into bed with a woman he has just met (before actually doing anything very much with her). Most of his time though is spent alone, indoors. During these periods of solitariness, he appears to have no clue about how to spend his time. As far as we can tell, he possesses no inner resources and has no clear ambition. He just sits on his own, drinking beer from a bottle and smoking, staring into space, like a child waiting to be told what to do next.

And from time to time he is, in fact, given instructions - and, to give him his due, he carries them out dutifully, fronting up for publicity events, ferrying his daughter to skating and, hilariously, allowing a full cast of his skull to be made for use as part of some future movie's special effects. This last activity involves his entire head being enveloped in a thick white goo, which has two holes made in it for him to breathe through. In a shot that does not move except to draw slowly closer to its subject, we watch as he sits patiently, docilely, submitting to this indignity without complaint.

And then his daughter - who has already won our hearts in a poignant scene in which she practises her ice dancing routine with a slightly clumsy seriousness (made all the more touching because of the way it echoes the jerks and grinds of the earlier, sleep-inducing pole dancers) - is thrust upon him for an extended stay. Like Saffy in Absolutely Fabulous, she turns out to have more of a grasp on reality than her parent. She is active and engaged. She is interested in testing herself and trying out new things. She cooks meals, rather than ordering room service. While her father lolls idly on the edge of an indoor pool, she dashes back and forth through the water. When there is nothing to do, she pulls out her sudoku book and diverts her mind. She does not just wait for things to happen to her. She does not submit to boredom.

The days pass. The pair go to Italy for a TV awards ceremony. They return. Their car breaks down and they have to call a mechanic. They lie by the pool of the hotel where Johnnie lives. They go to Las Vegas. The daughter leaves for summer camp. The film ends. Nothing dramatic occurs. There is no sparkly Hollywood epiphany. All the same, we realise that something has happened, although it is nothing spectacular. The daughter has coaxed her father out from behind the walls of the hotel into the sunlight for a brief time. In her company, he has become dimly aware that he is not just a mote of dust drifting through time and space. What will come of this vague step towards understanding we cannot tell. There is no sense at the end of the film that a great redemption has taken place. He may not yet be ready to be master of his own destiny. All we can say is that, whereas at the beginning of the movie he emerged from his car after driving around and around in circles, in the closing scene, looking almost purposeful, he emerges from it after driving in a straight line.

Which is not to suggest that the film is pointless. While it is pretty uneventful and could not be said to move at breakneck speed, it is intriguing. Although some critics have argued that the main character is not only fairly unsympathetic, but also represents a tiny privileged elite and therefore has nothing to tell us, I disagree. Johnnie is certainly infuriating - has he never heard of reading a book (or even a newspaper or, indeed, an article on the internet - there is no sign that he has ever come across a computer) - but the irritating aspects of his personality are also the ones that connect him to the rest of the population. It is not only film stars who have been duped into believing that the meaning of life is to be found in material objects and distracted hedonism, in vivid sensation and high-speed cars. The irony is that Johnnie is part of the system of myth-making that has helped create the false assumptions that have led him to his current emotional dead end. In a similar irony, the film, while set in Hollywood and the shallow outposts of its empire, is itself a thoughtful alternative to the dangerous myths that Hollywood - with Johnnie's help - creates.

Wednesday, 26 January 2011

All Pigs Great and Small

When I was young, my brother and I were regularly sent off to stay with some cousins who had a nanny who was so vile we used to beg our parents not to make us go. They took not a blind bit of notice, of course, waving us off without a trace of remorse (and, as they would I'm sure point out, if they read this, we did actually survive [but the scars, my dear, the terrible emotional scars]). Anyway in the end I discovered that there was only one truly effective refuge from the horror of the subsequent fortnight - hiding in a cupboard with Lord Emsworth and the Empress of Blandings.

For those who haven't had the pleasure, (you poor things), Emsworth and the Empress are the creations of PG Wodehouse. Emsworth is a pig besotted earl, 'a backwoods peer to end all backwoods peers' whose normal attire is 'baggy flannel trousers, an old shooting coat with holes in the elbows, and a hat which would have been rejected disdainfully by the least fastidious of tramps'. The Empress is 'his pre-eminent sow, three times silver medallist in the Fat Pigs class at the Shropshire Agricultural Show.'

The books Wodehouse wrote about these two fine characters usually revolve around the attempts of the Duke of Dunstable to steal the Empress and the travails of Emsworth at the hands of a range of bossy sisters and brutal secretaries - with sub-plots involving hapless Bertie Wooster types who want to marry chorus girls, to the consternation of their aunts. During our stays at the house of the scary nanny, I felt as hunted as Emsworth is by his overbearing sisters. I suppose that was what made the stories such a source of comfort then - although, to be honest, they still are, even though there is no nanny-tyrant on the horizon.

Anyway, I thought of the Empress - and, by implication, Lord Emsworth - again today, when I found a series of pictures of pigs in my picture file. They came from the Telegraph weekend magazine and the photographer was Andrew Perris. I'm not sure why I kept them but they are a rather magnificent bunch, (even if some of them might look a little out of place at the Shropshire Agricultural Show):

1. This one matches most closely my image of the Empress of Blandings. The caption on it explains that it is an Oxford Sandy & Black sow. The breed, apparently, first emerged 200 years ago. It is often called the Plum Pudding pig and its members are known for being good walkers.

2. This one is a Gloucestershire Old Spot, a breed that became well-known after the First World War but, by 1974, was classified as endangered. This might have had something to do with the fact that Gloucestershire Old Spots were much used as 'bacon pigs'.

3. This one comes from Belgium and is called a Pietrain (there should be an acute accent over the first 'e' but mine will not work today, for some reason). It is 'superbly meaty', which is fine if you don't like fat I suppose. On the other hand, if stressed it can drop dead and its extraordinarily large hams and short legs mean it cannot reproduce naturally. Nuff said, I think:

4. This tousled little creature hails from Hungary, we are told. I don't think you need me to add what is quite obvious from looking at it - namely, that from a distance it looks like a sheep:

5. This amazing beast is a Kune Kune which means 'fat and round', according to the caption (in Maori, I assume, since this is a Maori pig from New Zealand, although no-one knows how it got there.) It is very hairy and never curls its tail. The Maori, if the Telegraph is to be believed, did not usually eat these animals, but kept them as outdoor pets. This statement is contradicted slightly by the information that the Maori kept their pigs for lard, in which they preserved their dried meat.

6. Last, and, in size, least, comes the Black Vietnamese Pot-bellied pig, which was developed in the 1960s. For a while there was a craze for these as pets in the US at some unspecified time and they sold for thousands of dollars. They have to be slaughtered young if they are to be used for meat, so, to anyone who has one and was thinking about eating it, it is probably already too late:

For those who haven't had the pleasure, (you poor things), Emsworth and the Empress are the creations of PG Wodehouse. Emsworth is a pig besotted earl, 'a backwoods peer to end all backwoods peers' whose normal attire is 'baggy flannel trousers, an old shooting coat with holes in the elbows, and a hat which would have been rejected disdainfully by the least fastidious of tramps'. The Empress is 'his pre-eminent sow, three times silver medallist in the Fat Pigs class at the Shropshire Agricultural Show.'

The books Wodehouse wrote about these two fine characters usually revolve around the attempts of the Duke of Dunstable to steal the Empress and the travails of Emsworth at the hands of a range of bossy sisters and brutal secretaries - with sub-plots involving hapless Bertie Wooster types who want to marry chorus girls, to the consternation of their aunts. During our stays at the house of the scary nanny, I felt as hunted as Emsworth is by his overbearing sisters. I suppose that was what made the stories such a source of comfort then - although, to be honest, they still are, even though there is no nanny-tyrant on the horizon.

Anyway, I thought of the Empress - and, by implication, Lord Emsworth - again today, when I found a series of pictures of pigs in my picture file. They came from the Telegraph weekend magazine and the photographer was Andrew Perris. I'm not sure why I kept them but they are a rather magnificent bunch, (even if some of them might look a little out of place at the Shropshire Agricultural Show):

1. This one matches most closely my image of the Empress of Blandings. The caption on it explains that it is an Oxford Sandy & Black sow. The breed, apparently, first emerged 200 years ago. It is often called the Plum Pudding pig and its members are known for being good walkers.

2. This one is a Gloucestershire Old Spot, a breed that became well-known after the First World War but, by 1974, was classified as endangered. This might have had something to do with the fact that Gloucestershire Old Spots were much used as 'bacon pigs'.

3. This one comes from Belgium and is called a Pietrain (there should be an acute accent over the first 'e' but mine will not work today, for some reason). It is 'superbly meaty', which is fine if you don't like fat I suppose. On the other hand, if stressed it can drop dead and its extraordinarily large hams and short legs mean it cannot reproduce naturally. Nuff said, I think:

4. This tousled little creature hails from Hungary, we are told. I don't think you need me to add what is quite obvious from looking at it - namely, that from a distance it looks like a sheep:

5. This amazing beast is a Kune Kune which means 'fat and round', according to the caption (in Maori, I assume, since this is a Maori pig from New Zealand, although no-one knows how it got there.) It is very hairy and never curls its tail. The Maori, if the Telegraph is to be believed, did not usually eat these animals, but kept them as outdoor pets. This statement is contradicted slightly by the information that the Maori kept their pigs for lard, in which they preserved their dried meat.

6. Last, and, in size, least, comes the Black Vietnamese Pot-bellied pig, which was developed in the 1960s. For a while there was a craze for these as pets in the US at some unspecified time and they sold for thousands of dollars. They have to be slaughtered young if they are to be used for meat, so, to anyone who has one and was thinking about eating it, it is probably already too late:

Tuesday, 25 January 2011

Anglo-Saxon and Antipodean Attitudes

It is Australia Day and so it seems a good time to remember that this blog was supposed to be my means - as a mongrel, born with two nationalities - of sorting through the differences and similarities I notice between Britain and Australia.

Funnily enough, the area of taxation is one where I see a surprisingly clear gulf between the peoples of each nation. This first struck me when I saw the reaction to the fact that the Greens Party in Australia has on its agenda the introduction of an inheritance tax. This is something the vast majority of Australians almost instinctively reject, despite the fact that the Greens' proposal is only that inheritance tax kick in when the person who dies leaves an estate of over $5 milllion, excluding their house and any farmland they may have.

The proposal itself and the reaction to it both highlight, I think, how much less socialist in attitude Australia is than Britain, despite the fact that we have a Labour (or as they insist on calling themselves, thanks to O'Malley, 'Labor') government, while over there a hybrid Tory government is in power. In contrast to Australia, in Britain the general reaction to the Tory proposal to reduce the number of people being subjected to inheritance tax was that it was outrageously generous to the Toffs, whereas here any tax even mildly approaching that in severity would be regarded as an attack on the aspirant Aussie battlers.

My theory, to quote Monty Python, is that the difference in attitude lies in a difference in outlook. Australians don't like more taxes on the wealthy because we all believe that we ourselves can one day become rich. The barriers to achievement and success are, at least in the eyes of the populace, not too hard to get over in this country. By contrast, in Britain you have the politics of envy, fuelled by the belief, usually borne out by experience, that where you start is where you'll stay and the likelihood of achieving what the rich have is virtually nil - and therefore,'Let's get the bastards.'

Funnily enough, the area of taxation is one where I see a surprisingly clear gulf between the peoples of each nation. This first struck me when I saw the reaction to the fact that the Greens Party in Australia has on its agenda the introduction of an inheritance tax. This is something the vast majority of Australians almost instinctively reject, despite the fact that the Greens' proposal is only that inheritance tax kick in when the person who dies leaves an estate of over $5 milllion, excluding their house and any farmland they may have.

The proposal itself and the reaction to it both highlight, I think, how much less socialist in attitude Australia is than Britain, despite the fact that we have a Labour (or as they insist on calling themselves, thanks to O'Malley, 'Labor') government, while over there a hybrid Tory government is in power. In contrast to Australia, in Britain the general reaction to the Tory proposal to reduce the number of people being subjected to inheritance tax was that it was outrageously generous to the Toffs, whereas here any tax even mildly approaching that in severity would be regarded as an attack on the aspirant Aussie battlers.

My theory, to quote Monty Python, is that the difference in attitude lies in a difference in outlook. Australians don't like more taxes on the wealthy because we all believe that we ourselves can one day become rich. The barriers to achievement and success are, at least in the eyes of the populace, not too hard to get over in this country. By contrast, in Britain you have the politics of envy, fuelled by the belief, usually borne out by experience, that where you start is where you'll stay and the likelihood of achieving what the rich have is virtually nil - and therefore,'Let's get the bastards.'

Monday, 24 January 2011

Battered Penguins I

Having been disappointed by contemporary literature once or twice recently (although not always), I've started reading old Penguins - only the ones printed before they brought in big writing on the front and shiny covers - instead. Which is why, on the way to Sydney the other day, I popped in (this is beginning to sound like something from Round the Horne and Julian and Sandy, but it isn't) to the Georgian house facing the railway station in Goulburn, where they sell old books. The room that I think may once have been the old dining-room is now devoted almost exclusively to Penguins. Indeed, since my last visit, the Penguins have been multiplying - there are now so many in there that they have escaped the shelves and sit about on the floor in teetering alphabetical stacks.

I eased the overcrowding by buying four or five of the things and I've just finished reading the first of that batch. It's by someone called Honor Tracy, a writer I thought at the time that I'd never heard of. Now though I've realised that she was the woman - either under her pen name or her real name, (which was Lilbush Wingfield) - who was supposed to have been the recipient of a love letter from John Betjeman, which later turned out to be Bevis Hillier's idea of a joke (the first letters of each sentence were an acrostic, spelling out the phrase, 'AN Wilson is a shit' - oh how we laughed, the wit, the rapier-like wit, of the man).

Anyway, Tracy, I now know, wrote lots of things and was quite celebrated in her day. In fact, according to the New York Times, her work was described in a 1972 book called Contemporary Novelists as 'designed to be read with a glass of sherry in one hand'. Sadly, I didn't discover this until after I'd finished the one I bought, which is called The Straight and Narrow Path. Still, even without the sherry, it was very entertaining - indeed, I've just learned (thank you, Mr Google) that it was named 'Farce of the Year' by Time magazine in 1956.

The book is set in Ireland and concerns a libel case brought by the Canon of a country parish against a visiting English academic. I have to confess that to begin with I wondered if Tracy was being entirely fair to the Irish. At first it did seem to me, in my hopelessly politically correct way, that she might be balancing on the very edge of racism in her portrayal of her Irish characters largely as 'colourful rogues'. However, I was reassured a little when I found out that the plot of the book pretty much exactly mirrors something that actually happened to Tracy. Presumably, therefore, she wrote from experience rather than prejudice, I reasoned. I also gradually came to realise that she had a genuine affection for and understanding of the Irish and was implying that they go about things differently from the English, rather than less efficiently.

And even if Tracy were less than entirely tolerant, in the end I'm not sure it would have mattered all that much. This is because she is very funny. Her portrait of village postal arrangements, her depiction of a dinner at a decaying old house, the vision she gives us of ruby cufflinks being pressed into a sponging Englishman's hand - it 'closed on them like a sprung trap while its owner repeated over and over that it was a shame to rob him and oh, he simply couldn't' - these are just a few of the many things in the book that made me laugh. I would like to quote them all, but I will restrict myself to my favourite - her description of a man who has just made his confession as 'much restored ... looking about him with the alert, refreshed air of a baby who has just been sick in someone's lap.'

By the closing pages, as well as a great deal of amusement, an interesting portrait of rural Ireland and its ways emerges from the book - it is a world in which the Catholic church could not be said to be an entirely positive influence. I'm sure the novel must still be available on Abebooks (some soiling to frontispiece but otherwise in fair to good condition) and I recommend it to anyone who wants an entertaining read.

Sunday, 23 January 2011

Tact

I was sitting behind a car with a number plate bearing this slogan yesterday:

It struck me as bordering on the provocative, given recent 'flood events'. If my car bore the same message, I think I might try obscuring the words with mud for a week or two. If someone who has lost everything - or almost everything - reads them on a bad day, it could be just the final straw.

It struck me as bordering on the provocative, given recent 'flood events'. If my car bore the same message, I think I might try obscuring the words with mud for a week or two. If someone who has lost everything - or almost everything - reads them on a bad day, it could be just the final straw.

Friday, 21 January 2011

Words and Phrases that Make Me Ill at Ease

'Gestational carrier', the phrase used by Nicole Kidman and her husband, to refer to the woman who bore them a second child.

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Is it Just Me?

When I go into a hotel room and see signs like these:

the only thing I want to do is hurl all the towels and sheets on the floor immediately and trample them with muddy boots. Am I alone, or is there anyone else in the world who reacts in this appalling way?

the only thing I want to do is hurl all the towels and sheets on the floor immediately and trample them with muddy boots. Am I alone, or is there anyone else in the world who reacts in this appalling way?

Wednesday, 19 January 2011

A Trojan Boar

I don't know if it's due to the wonderful meal I had last night (the kind that prompts thoughts of Spartan regimes in the morning) that I don't find the thought of this dish, described in the 6th January London Review of Books, entirely appetising:

'Wild boar a la Troyenne [was served] at a banquet given by Servilius Rullus for Marcus Tullius Cicero, after the latter's victory over Catiline in 63 BC.

A young Sicilian cook prepared the dish, which was carried in by four Ethiopian slaves. Baskets of dates were suspended from the boar's tusks. Piglets in pastry surrounded it. When the boar was cut open, a second animal was discovered within it, and a third, and a fourth. The sequence was finally terminated by a fig-pecker. ('If a fig-pecker could grow as big as a pheasant, it would be worth the price of an acre of land,' Brillat-Savarin adjudged 19 centuries later, before divulging Canon Charcot's method of consumption: pull out the gizzard and swallow the bird whole...)

By the time of Petronius the dish was already an absurdity. Decapitated at the table, live thrushes, (the poor man's fig-pecker) fluttered out of the boar's open neck to be recaptured by slaves acting the parts of huntsmen. A second slash of the sabre and sausages tumbled out in place of gut. The boar's vital organs were blood puddings.'

I suppose it beats fish fingers.

'Wild boar a la Troyenne [was served] at a banquet given by Servilius Rullus for Marcus Tullius Cicero, after the latter's victory over Catiline in 63 BC.

A young Sicilian cook prepared the dish, which was carried in by four Ethiopian slaves. Baskets of dates were suspended from the boar's tusks. Piglets in pastry surrounded it. When the boar was cut open, a second animal was discovered within it, and a third, and a fourth. The sequence was finally terminated by a fig-pecker. ('If a fig-pecker could grow as big as a pheasant, it would be worth the price of an acre of land,' Brillat-Savarin adjudged 19 centuries later, before divulging Canon Charcot's method of consumption: pull out the gizzard and swallow the bird whole...)

By the time of Petronius the dish was already an absurdity. Decapitated at the table, live thrushes, (the poor man's fig-pecker) fluttered out of the boar's open neck to be recaptured by slaves acting the parts of huntsmen. A second slash of the sabre and sausages tumbled out in place of gut. The boar's vital organs were blood puddings.'

I suppose it beats fish fingers.

Tuesday, 18 January 2011

Musical Suggestions

I'm going to be doing a bit of driving over the next few days so I will need something to listen to. I have my trusty favourites, of course - Lady Gaga's splendid oeuvre; Mendelssohn's final string quartet; Amy Macdonald's 'This is the Life' (thank you, Worm, I never tire of it), playing on an alternating loop with the first part of Handel's Messiah. But I feel I should break out of my audio rut and try something new - after all, that is how I discovered Amy Macdonald. Any suggestions - especially for things you can play at top volume as you belt along the highway - would be welcomed with open ears.

Monday, 17 January 2011

Dark and Wonderful

When I was at school, the science teacher was one of the only known women over 40 to still wear her hair in pig tails. Needless to say, she looked silly, which was distracting. She was also rumoured to be a member of the Plymouth Brethren, on account of the fact that she never shaved her legs. As a consequence, beneath her flesh coloured stockings, (flesh coloured if you came from a distinctly orange-tinged line of human beings), swirls of lush black hair were visible, like some kind of creepy psychedelic dream. When she was carted off with a nervous breakdown, (yes, I think it probably was our fault), she was replaced by Mr Harris who, no matter the season, (and take it from me, it can get pretty warm in Mittagong), always wore a tweed jacket, (the only time I ever saw him remove it was on my first ever trip to Sydney, which was an excursion to the blood bank to watch him donate a couple of pints). His main aim in life seemed to be describing the extraordinarily gory details of the first night of his honeymoon as often as possible (this was, presumably, his primitive attempt at therapy). I dropped science soon after he arrived.

And now I feel cheated. Because I've just been reading an article in the New York Times about something called 'dark matter' and, while I don't have the faintest idea what dark matter is, I have discovered that science is actually beautiful and very strange. Those teachers of mine never mentioned that as they handed round the bunsen burners. The science they presented to us was a place of certainty, which was what made it so dull, I thought.

The phrases in the article that appeal to me particularly, hinting at mysteries we never heard about in Science Lab 4A, are these:

'Although nothing can move through space faster than the speed of light, there’s no limit on how fast space itself can expand'

'The past will have drifted beyond the cliffs of space.'

'Sometimes the true nature of reality beckons from just beyond the horizon.'

The full article can be found here.

And now I feel cheated. Because I've just been reading an article in the New York Times about something called 'dark matter' and, while I don't have the faintest idea what dark matter is, I have discovered that science is actually beautiful and very strange. Those teachers of mine never mentioned that as they handed round the bunsen burners. The science they presented to us was a place of certainty, which was what made it so dull, I thought.

The phrases in the article that appeal to me particularly, hinting at mysteries we never heard about in Science Lab 4A, are these:

'Although nothing can move through space faster than the speed of light, there’s no limit on how fast space itself can expand'

'The past will have drifted beyond the cliffs of space.'

'Sometimes the true nature of reality beckons from just beyond the horizon.'

The full article can be found here.

Sunday, 16 January 2011

The Politics of Change

So "$5.50" is what I'm asked for and I hand over a five dollar note and a one dollar coin. "You wouldn't have the fifty cents, would you?" "Sorry?" "You wouldn't have a fifty cent coin?"

If I had a bloody fifty cent coin, I'd give it to you, unless I needed it for reasons of my own (which seems unlikely, since they are horrible oversized clumsy sorts of coins, the monetary equivalent of those sad great lummocking infants of whom there was a representative in every primary school class that I was ever part of [and, no, it wasn't always me]).

I hate this importuning of my purse contents by shopkeepers (is importuning the right word, I've never used it before and have only a hazy idea of what it really means), this clamouring for coins I must surely be concealing about my person. Listen: if I had them, I'd cough them up, provided I felt like it - and, should I decide I want to retain them for my own private pleasure, then that's my prerogative too. The thing is, I'm the customer; I'm paying; if I feel like doling the entire cost out in one cent pieces, that ought to be all right by you (well, maybe not one cent pieces, given they've been abolished, in a move which I still can't help believing is actually a challenge to the whole idea of the value of money - if everything's rounded to the nearest five, does that mean that one has no value, and, if it does, surely that must also mean that a sum made up of one hundred thousand ones is also valueless).

And what about all that, "If you just give me 49 cents then I can give you 30" nonsense? Even in my glory days working in retail - well, in a takeaway shop run by Armenians at the bottom of Bourke Street (and only for the time it took the Armenians to make the wise business calculation that it might be cheaper to employ their hideously overweight son behind the counter, since he was already consuming most of the profits on the other side of the glass panelling), I never got my head around those arcane calculations.

Of course that might have been another factor in my being 'let go', now I come to think of it. Perhaps if I'd mastered the "You give me a 10 cent piece, and I give you 67 cents and then you give me a dollar coin and we'll be square" equations, I might now be in charge of a flourishing chain of Subway franchises and living in splendour in one of those places real estate agents like to call "a dress circle location". Ah splendid dreams, ah squandered glories. Did my lack of change skills completely change my life?

If I had a bloody fifty cent coin, I'd give it to you, unless I needed it for reasons of my own (which seems unlikely, since they are horrible oversized clumsy sorts of coins, the monetary equivalent of those sad great lummocking infants of whom there was a representative in every primary school class that I was ever part of [and, no, it wasn't always me]).

I hate this importuning of my purse contents by shopkeepers (is importuning the right word, I've never used it before and have only a hazy idea of what it really means), this clamouring for coins I must surely be concealing about my person. Listen: if I had them, I'd cough them up, provided I felt like it - and, should I decide I want to retain them for my own private pleasure, then that's my prerogative too. The thing is, I'm the customer; I'm paying; if I feel like doling the entire cost out in one cent pieces, that ought to be all right by you (well, maybe not one cent pieces, given they've been abolished, in a move which I still can't help believing is actually a challenge to the whole idea of the value of money - if everything's rounded to the nearest five, does that mean that one has no value, and, if it does, surely that must also mean that a sum made up of one hundred thousand ones is also valueless).

And what about all that, "If you just give me 49 cents then I can give you 30" nonsense? Even in my glory days working in retail - well, in a takeaway shop run by Armenians at the bottom of Bourke Street (and only for the time it took the Armenians to make the wise business calculation that it might be cheaper to employ their hideously overweight son behind the counter, since he was already consuming most of the profits on the other side of the glass panelling), I never got my head around those arcane calculations.

Of course that might have been another factor in my being 'let go', now I come to think of it. Perhaps if I'd mastered the "You give me a 10 cent piece, and I give you 67 cents and then you give me a dollar coin and we'll be square" equations, I might now be in charge of a flourishing chain of Subway franchises and living in splendour in one of those places real estate agents like to call "a dress circle location". Ah splendid dreams, ah squandered glories. Did my lack of change skills completely change my life?

Endangered Species

When I was a child, I lived around the corner from a shop called Geo. White, Stationers. It was just across from Cullen's and, in the other direction, Macfisheries and the establishment known in our household as 'the Smoking Man.' I was regularly despatched to the Smoking Man by my father, to get him a packet of those fags that had a rather nice picture of a bearded sailor on them (Capstans?).

Anyway, Geo. White was a shop I spent a lot of time in. In fact, I shocked my family once by saving up my pocket money until I had five shillings and spending the lot on a really nice block of paper I found in there. As a result of the fuss made about this purchase, all the pleasure I might otherwise have felt each time I used a sheet of the paper was blotted out by guilt.

All of this is by way of saying, 'I love stationery'. And it is because I love stationery that I have been worrying about its future in what promises to be a largely paper-free world. 'What will become of paperclips?', I've been wondering (although I was cheered by an article in praise of them in one of the papers recently) and 'Will pencil sharpeners like my trusty brass one -

(Isn't it beautiful? Strange how I'd never noticed before that it was made in Germany) -

survive?' I'm not sure that I was reassured about the survival chances of pencil sharpeners by the news that this chap had set up in business (he says it's not a joke, but I'm not entirely convinced). I was pleased though to read this hymn to the act of pencil sharpening, printed in November in the Weekend Australian:

(And, before anyone says I'm being an alarmist, I should point out that, according to my favourite pen shop, blotting paper is pretty much a thing of the past.)

Anyway, Geo. White was a shop I spent a lot of time in. In fact, I shocked my family once by saving up my pocket money until I had five shillings and spending the lot on a really nice block of paper I found in there. As a result of the fuss made about this purchase, all the pleasure I might otherwise have felt each time I used a sheet of the paper was blotted out by guilt.

All of this is by way of saying, 'I love stationery'. And it is because I love stationery that I have been worrying about its future in what promises to be a largely paper-free world. 'What will become of paperclips?', I've been wondering (although I was cheered by an article in praise of them in one of the papers recently) and 'Will pencil sharpeners like my trusty brass one -

(Isn't it beautiful? Strange how I'd never noticed before that it was made in Germany) -

survive?' I'm not sure that I was reassured about the survival chances of pencil sharpeners by the news that this chap had set up in business (he says it's not a joke, but I'm not entirely convinced). I was pleased though to read this hymn to the act of pencil sharpening, printed in November in the Weekend Australian:

(And, before anyone says I'm being an alarmist, I should point out that, according to my favourite pen shop, blotting paper is pretty much a thing of the past.)

Friday, 14 January 2011

The End of Suffering

In Australia at least, no-one is suffering any more. Despite drought, bush-fire and flood, suffering has become a thing of the past. These days, those among us who are robbed of belongings, livelihood and even relatives by natural disaster never suffer; we only hurt. At the moment, whole communities in Queensland are hurting apparently. Who or what exactly they are hurting is never explained.

Wednesday, 12 January 2011

Twisting Fate

In Victoria, a couple who have three sons and had a baby daughter who died are seeking to conceive another daughter through IVF. They recently 'terminated' twin boys because they cannot continue to have unlimited numbers of children and what they want is a daughter. The independent Patient Review Panel recently rejected their application to choose the gender of their next child, using IVF. The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal is now considering their appeal against that decision. The male of the couple gave the following evidence as part of that appeal:

'"After what we have been through we think we are due for a bit of luck," the man said.

"We want to be given the opportunity to have a girl."

"We know we definitely won't be replacing her in any way, but want the chance to have the baby girl we don't have."'

How do people reach adulthood still believing that because things have gone wrong for them in the past they are 'due for a bit of luck'? Have they not observed the world at all?

(Meanwhile in Queensland, 'four children, including a three-year-old torn from his mother's arms by a killer torrent have been confirmed drowned', a helpless bystander in Grantham reported screams coming from inside a house smashed off its foundations and hurtled along in the deadly torrent: 'This home just floated past with people yelling out for help ... but no-one could help them', and a woman who went to buy gumboots for her husband came home to find her house had been 'sent down the creek, along with their three sheds, tractors, cars and all their worldly goods. Nothing remains', and there is no sign of her husband. Sorry to bang on. [On a lighter note, someone in Brisbane has just tweeted, 'I don't know if you can call it panicbuying but the couple ahead at the 7/11 just bought 9 packs of condoms'].)

'"After what we have been through we think we are due for a bit of luck," the man said.

"We want to be given the opportunity to have a girl."

"We know we definitely won't be replacing her in any way, but want the chance to have the baby girl we don't have."'

How do people reach adulthood still believing that because things have gone wrong for them in the past they are 'due for a bit of luck'? Have they not observed the world at all?

(Meanwhile in Queensland, 'four children, including a three-year-old torn from his mother's arms by a killer torrent have been confirmed drowned', a helpless bystander in Grantham reported screams coming from inside a house smashed off its foundations and hurtled along in the deadly torrent: 'This home just floated past with people yelling out for help ... but no-one could help them', and a woman who went to buy gumboots for her husband came home to find her house had been 'sent down the creek, along with their three sheds, tractors, cars and all their worldly goods. Nothing remains', and there is no sign of her husband. Sorry to bang on. [On a lighter note, someone in Brisbane has just tweeted, 'I don't know if you can call it panicbuying but the couple ahead at the 7/11 just bought 9 packs of condoms'].)

Same Again

The floods in Queensland are still on my mind. Yesterday's paper carried reports from Toowoomba, including a description of a woman in a car 'that was swallowed by the "tsunami" that erupted from East Creek ...The woman climbed onto the roof of the car and grasped the outstretched hand of a bystander, who could not hold her.' She was washed into a storm drain and her body has now been recovered. Sadly, there is no trace of three children who 'were last seen on a corner of downtown Russell Street as the flash flood bore down'.

As a slight distraction, I've been trying to think of films or books or plays that include rain as a major feature. There is, of course, Peter Weir's Last Wave. I also vaguely remember that The Year of Living Dangerously unfolded during monsoonal rains. There was a play I saw in London called, I think, Three Days of Rain. I'm stuck for novels at the moment. I'm sure I'm missing lots of obvious things - any suggestions?

As a slight distraction, I've been trying to think of films or books or plays that include rain as a major feature. There is, of course, Peter Weir's Last Wave. I also vaguely remember that The Year of Living Dangerously unfolded during monsoonal rains. There was a play I saw in London called, I think, Three Days of Rain. I'm stuck for novels at the moment. I'm sure I'm missing lots of obvious things - any suggestions?

Monday, 10 January 2011

What We Have Learned from the Queensland Floods

1. That the official unit of measurement in a 'flood event' is 'a Sydney harbour'.

2. That the thing to do, when in danger from flooding, is 'to brace' (Queensland is 'braced' for more rain and flood towns are 'bracing' themselves and officials are warning residents to 'brace' and on and on it goes).

3. That repeating at regular intervals the phrase 'Queenslanders are doing it tough' will make things better, if all else fails - otherwise, why would our Prime Minister keep saying it?

If none of these things seems very enlightening and you feel like helping the poor benighted souls who have lost their homes and possessions and are up to their knees in mud and brown snakes, you can always donate a bob or two to the victims here.

2. That the thing to do, when in danger from flooding, is 'to brace' (Queensland is 'braced' for more rain and flood towns are 'bracing' themselves and officials are warning residents to 'brace' and on and on it goes).

3. That repeating at regular intervals the phrase 'Queenslanders are doing it tough' will make things better, if all else fails - otherwise, why would our Prime Minister keep saying it?

If none of these things seems very enlightening and you feel like helping the poor benighted souls who have lost their homes and possessions and are up to their knees in mud and brown snakes, you can always donate a bob or two to the victims here.

Saturday, 8 January 2011

Suburban Soundscapes

Sitting in bed drinking tea this morning, our conversation was drowned out by the usual Sunday morning noise of tumbling glass. Our neighbours on the other side from these ones (who never, someone down the street complained to me recently, put out recycling at all - but what would they put out, given that they don't read newspapers and never drink wine?) were hurling their Friday and Saturday night empties - cab sav for him, chilled sauvignon blanc from NZ for her, unpatriotic creature - into the recycling. 'The battle cry of the middle classes,' my husband yelled above the din.

Friday, 7 January 2011

Chronicles of Not Completely Wasted Time

I spent quite a long time in the dim dark past learning Russian. It wasn't a complete waste of time - I met my husband in Moscow airport, which was a pretty good outcome - but I can't say I draw upon my hard earned - and mostly long ago leaked away - knowledge on a daily basis. Which is why I am going to seize the opportunity of Orthodox Christmas to say С Рождеством Христовым. Желаю всем добра, cчастья и любви (I bet I've got some part of that wrong.)

Thursday, 6 January 2011

Fattipuffs and Thinnifers

Up at the local shops, things are slowly getting back to normal, after the glorious annual dream of wearing shorts forever - aka Christmas and New Year. People are emerging from their lairs, shops are reopening. It's all a bit jarring, to tell the truth.

For instance, this morning I was nearly deafened by a woman coming out of the supermarket as I was going in. 'G'day, Dave,' she yelled, 'you look as slim as.' 'Thanks,' said the tall man she was greeting, 'I am a thin person really - I just got out of hand.'

'I am a thin person really.' Aren't we all.

For instance, this morning I was nearly deafened by a woman coming out of the supermarket as I was going in. 'G'day, Dave,' she yelled, 'you look as slim as.' 'Thanks,' said the tall man she was greeting, 'I am a thin person really - I just got out of hand.'

'I am a thin person really.' Aren't we all.

Wednesday, 5 January 2011

Scissors, Paper

In most areas of life, I am fairly grown up, but I have never lost a fondness for the major activity of my primary school years - cutting things up. As a result, I have files of 'Articles that Might Be Interesting to Read', 'Articles that Made Me Laugh', 'Brilliant Cartoons', 'Poems I Like' and 'Amazing Photographs'.

This morning, I have been leafing through this last folder, and here are some of my favourites from among its contents:

1. A photograph by Hiroshi Sugimoto of Queen Victoria, taken from the 13 August, 2001 issue of the New Yorker, where it was publicising a photography exhibition at the Guggenheim SoHo. There was no other information given about it - such as why she was wearing that get up, why she allowed herself to be photographed in it and what exactly she was thinking as she stared so implacably at the lens:

2. A picture of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor taken in Paris in 1951 by Cartier-Bresson. This was published in Antiques & Art in Victoria to publicise an exhibition of photographs from the British National Portrait Gallery that was held between 24 March and 13 May 2001 at Bendigo Art Gallery. We went to see the film called The King's Speech last week and the photograph seems more intriguing than ever as a result:

3. A photograph illustrating an article by Peter Schjeldahl from the 6 August, 2007 issue of the New Yorker. It is of Gerald and Sara Murphy, a wealthy but rather tragic couple who lived in Antibes in the 1920s and were friends of Cole Porter, Picasso, Man Ray, Dorothy Parker, Ernest Hemingway and F.Scott Fizgerald (they were the models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night.) To F. Scott Fitzgerald, Schjeldahl writes, the Murphys served "as symbols of the great theme of the Lost Generation: romantic disappointment, given intensity by the majesty of the dreams at stake." To support his case Schjeldahl quotes a letter Murphy wrote to Fitzgerald, saying, "Only the invented part of our life - the unreal part - has had any scheme, any beauty," and another by Zelda Fitzgerald following her husband's death in which, he tells us, "she writes that Scott's love of the Murphys reflected a 'devotion to those that he felt were contributing to the aesthetic and spiritual purposes of life'":

4. Finally, (and especially for the attention of Frank Wilson, who, I seem to remember, was talking with pleasure on his Books Inq blog about receiving some Bernstein recordings as a present recently), a photograph that again comes from the New Yorker - its 15 December 2008 issue this time. This picture never fails to make me smile - it shows Bernstein conducting Mahler in 1970, with such abandon that I doubt he was actually conveying anything to the players in the orchestra. Never mind - at lesat he seems to have been having a really fantastically good time:

This morning, I have been leafing through this last folder, and here are some of my favourites from among its contents:

1. A photograph by Hiroshi Sugimoto of Queen Victoria, taken from the 13 August, 2001 issue of the New Yorker, where it was publicising a photography exhibition at the Guggenheim SoHo. There was no other information given about it - such as why she was wearing that get up, why she allowed herself to be photographed in it and what exactly she was thinking as she stared so implacably at the lens:

2. A picture of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor taken in Paris in 1951 by Cartier-Bresson. This was published in Antiques & Art in Victoria to publicise an exhibition of photographs from the British National Portrait Gallery that was held between 24 March and 13 May 2001 at Bendigo Art Gallery. We went to see the film called The King's Speech last week and the photograph seems more intriguing than ever as a result:

3. A photograph illustrating an article by Peter Schjeldahl from the 6 August, 2007 issue of the New Yorker. It is of Gerald and Sara Murphy, a wealthy but rather tragic couple who lived in Antibes in the 1920s and were friends of Cole Porter, Picasso, Man Ray, Dorothy Parker, Ernest Hemingway and F.Scott Fizgerald (they were the models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night.) To F. Scott Fitzgerald, Schjeldahl writes, the Murphys served "as symbols of the great theme of the Lost Generation: romantic disappointment, given intensity by the majesty of the dreams at stake." To support his case Schjeldahl quotes a letter Murphy wrote to Fitzgerald, saying, "Only the invented part of our life - the unreal part - has had any scheme, any beauty," and another by Zelda Fitzgerald following her husband's death in which, he tells us, "she writes that Scott's love of the Murphys reflected a 'devotion to those that he felt were contributing to the aesthetic and spiritual purposes of life'":

4. Finally, (and especially for the attention of Frank Wilson, who, I seem to remember, was talking with pleasure on his Books Inq blog about receiving some Bernstein recordings as a present recently), a photograph that again comes from the New Yorker - its 15 December 2008 issue this time. This picture never fails to make me smile - it shows Bernstein conducting Mahler in 1970, with such abandon that I doubt he was actually conveying anything to the players in the orchestra. Never mind - at lesat he seems to have been having a really fantastically good time:

Tuesday, 4 January 2011

Loose Tongues

A while ago I suggested that, had Philip Larkin been an Australian, (and I think it is possible to detect his considerable regret at not achieving that great honour, if you read his poems closely enough), he might have rephrased his famous lines about spring to suggest that wattle coming into flower is 'like something almost being said', rather than trees coming into leaf.

Well, now the wattle has come into flower. It has flowered to its heart's content. And, in the course of flowering, it has said everything it could possibly have wanted to say on all subjects that may have occurred to it. The result is sobering:

In an age where we are exhorted from all sides to 'Let it all out', where our streets ring to the whoops and squeals and whinnies of Oprah and her tribe - 'You go girl, you tell them' - this picture reveals a sadder story. The wattle has followed the contemporary advice to eschew reserve, it has got things off its chest - but at what cost?

In a former era - ie my childhood - things were very different. 'The less said the better', was the phrase that rang through those dim and distant years, along with, 'Least said, soonest mended,' and, of course, the perennial favourite, 'Would you please shut up.' I don't know if the world was a better place, but it was certainly quieter.

(On further reflection, I also suspect that a culture of greater restraint might have saved us from the candour with which Catherine Deveny expressed her 2010 New Year's wish for 'the legalisation of voluntary euthanasia. Or, in the case of my racist, bigoted, homophobic, judgmental, passive aggressive, narcissistic, wealthy grandmother, involuntary euthanasia', the openly meanspirited desire of the editor of Meanjin for "the people I love to be well and the people I don't love to be well also. Except for Tony Abbott" and the extraordinary ad hominem attack on Barry O'Farrell by Bob Ellis in yesterday's Drum - apparently no-one will vote for him, not because of his policies, but because he is "a serial fatty with an Irish name and a Greenstreet shape and a face like boiled bacon" - not to mention the periodic shrieks of silly Marieke Hardy.)

Well, now the wattle has come into flower. It has flowered to its heart's content. And, in the course of flowering, it has said everything it could possibly have wanted to say on all subjects that may have occurred to it. The result is sobering:

In an age where we are exhorted from all sides to 'Let it all out', where our streets ring to the whoops and squeals and whinnies of Oprah and her tribe - 'You go girl, you tell them' - this picture reveals a sadder story. The wattle has followed the contemporary advice to eschew reserve, it has got things off its chest - but at what cost?

In a former era - ie my childhood - things were very different. 'The less said the better', was the phrase that rang through those dim and distant years, along with, 'Least said, soonest mended,' and, of course, the perennial favourite, 'Would you please shut up.' I don't know if the world was a better place, but it was certainly quieter.

(On further reflection, I also suspect that a culture of greater restraint might have saved us from the candour with which Catherine Deveny expressed her 2010 New Year's wish for 'the legalisation of voluntary euthanasia. Or, in the case of my racist, bigoted, homophobic, judgmental, passive aggressive, narcissistic, wealthy grandmother, involuntary euthanasia', the openly meanspirited desire of the editor of Meanjin for "the people I love to be well and the people I don't love to be well also. Except for Tony Abbott" and the extraordinary ad hominem attack on Barry O'Farrell by Bob Ellis in yesterday's Drum - apparently no-one will vote for him, not because of his policies, but because he is "a serial fatty with an Irish name and a Greenstreet shape and a face like boiled bacon" - not to mention the periodic shrieks of silly Marieke Hardy.)

Sunday, 2 January 2011

Get Stuffed

In yesterday's Age newspaper there was an article about Mario Carnesi, who is a taxidermist in Melbourne. He became interested in his craft at the age of 10, when he spotted a stuffed duck at the house of a family friend. He waited some time before taking the plunge but one day, he tells the reporter:

"I was out at the rubbish tip with my dad. There was a dead seagull, but it hadn't been dead for long. It was still pretty fresh. I told dad I was going to take it home and stuff it and he sort of just looked at me and didn't say anything."

I like the picture that paragraph conjures up. To start with, the situation itself is appealing - a dad-and-boy-tip outing is the sort of thing the family at Yaralla might have indulged in. Then there is the father's superb true blue response - 'he sort of just looked at me and didn't say anything.' And the next phrase of the article - "The seagull went into the fridge" - points to a mother at home whose calm and tolerance I can only dream of. There are so many lessons in this story - at least for me.

(And before I finish, I should point out to my friend Polly, whose pets having been giving her a bit of grief lately, that Carnesi, according to the article, will "stuff a guinea pig for $220").

"I was out at the rubbish tip with my dad. There was a dead seagull, but it hadn't been dead for long. It was still pretty fresh. I told dad I was going to take it home and stuff it and he sort of just looked at me and didn't say anything."

I like the picture that paragraph conjures up. To start with, the situation itself is appealing - a dad-and-boy-tip outing is the sort of thing the family at Yaralla might have indulged in. Then there is the father's superb true blue response - 'he sort of just looked at me and didn't say anything.' And the next phrase of the article - "The seagull went into the fridge" - points to a mother at home whose calm and tolerance I can only dream of. There are so many lessons in this story - at least for me.

(And before I finish, I should point out to my friend Polly, whose pets having been giving her a bit of grief lately, that Carnesi, according to the article, will "stuff a guinea pig for $220").

The Unnamed by Joshua Ferris

I've just finished reading The Unnamed by Joshua Ferris. It tells the story of Tim Farnsworth, a partner in a New York law firm who is overwhelmed by an impulse to walk. By the time the book opens, he has already investigated every branch of medicine and every avenue of alternative treatment to find out what is wrong with him and how he might be cured. He has been in remission for a while, but now the strange urge is back. He cannot resist it. All he can do, at the end of each walk, when exhaustion overcomes the automatic movement of his legs, is call his wife and tell her where he's ended up so that she can find him and bring him home. They try one last device, a helmet that measures his brainwaves, to see if an explanation can be found for what is happening. It fails, Tim loses his job, fails a client charged with murder and eventually abandons his wife and daughter for a life spent permanently trudging across America.

This all sounds fairly unremitting and bleak, but The Unnamed also encompasses a love story (that between Tim and his wife), a touching account of a father's relationship with his daughter and a whodunnit. All the same, the bulk of the book deals with a single figure moving through the landscape by himself. Obviously, this means that Ferris has less opportunity to build up a rounded sense of the main characters than he did in his last novel, when he was portraying people in a group. Where that earlier book began in the first person plural, this one is a tale of being alone - but that is, I think, its theme. As we read the story of Tim's solitary travails - his struggle to 'be more than the sum of his urges' and to understand the parts of his existence that defy rational argument - 'So all your life you've searched and searched for a rational explanation ....while presuming there is one. But if there isn't?' 'There must be.' - we become conscious, inevitably, of our own essential aloneness.

And so we follow Tim through his long ordeal, observing him as he realises how much of his life has been spent carelessly - 'He wondered what kind of life he might have had if he had paid attention from the beginning.' - and as he discovers the animal pleasures of responding to his body's simplest needs - 'He wanted a drink of water. It was deliciously painful, his thirst, a thought to relish quenching'. We are watching him, we are not with him but outside - this is not a first person narrative - but we too are human, like him. His may be an extreme and especially puzzling imperative, but perhaps it is only a more dramatic version of the imperative we must all obey - the imperative to exist.

Each one of us has been given a life. We must live it, but few - if any - among us know why. Is it a task, or an opportunity? Like Tim, who 'discharged the walks with dutiful resignation, the way a busy hangman leaves for the day without scruple or gripe', we discharge our allotted time spans - there is very little else that we can do.

In the course of the novel, Ferris presents various possible answers to the question of existence. He suggests that science has become our new religion - 'They had always had faith ... in the existence of the One Guy, out there somewhere ... It was the One Guy they sought in Rochester, Minnesota, in San Francisco, in Switzerland and, closer to home, in doctors' offices from Manhattan to Buffalo' - but demonstrates that science fails in the face of true mystery, (at least in Tim's case). He dangles the possibility of a metaphysical, religious explanation, before reminding us that Tim's 'medication required tweaking from time to time.'

The Unnamed is a book that tackles the greatest and oldest of all the questions. It attempts to describe the unknown, the strange, the 'unnamed'. Ferris writes powerfully, plunging deep into his imagination (I hope he is not writing from experience) to produce a vivid portrait of an abandoned soul in torment. Somehow he avoids ever being boring. He is one of the most original writers working today.

This all sounds fairly unremitting and bleak, but The Unnamed also encompasses a love story (that between Tim and his wife), a touching account of a father's relationship with his daughter and a whodunnit. All the same, the bulk of the book deals with a single figure moving through the landscape by himself. Obviously, this means that Ferris has less opportunity to build up a rounded sense of the main characters than he did in his last novel, when he was portraying people in a group. Where that earlier book began in the first person plural, this one is a tale of being alone - but that is, I think, its theme. As we read the story of Tim's solitary travails - his struggle to 'be more than the sum of his urges' and to understand the parts of his existence that defy rational argument - 'So all your life you've searched and searched for a rational explanation ....while presuming there is one. But if there isn't?' 'There must be.' - we become conscious, inevitably, of our own essential aloneness.

And so we follow Tim through his long ordeal, observing him as he realises how much of his life has been spent carelessly - 'He wondered what kind of life he might have had if he had paid attention from the beginning.' - and as he discovers the animal pleasures of responding to his body's simplest needs - 'He wanted a drink of water. It was deliciously painful, his thirst, a thought to relish quenching'. We are watching him, we are not with him but outside - this is not a first person narrative - but we too are human, like him. His may be an extreme and especially puzzling imperative, but perhaps it is only a more dramatic version of the imperative we must all obey - the imperative to exist.