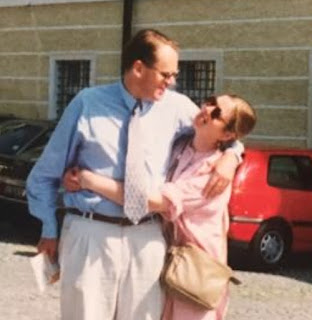

On 11 May, my brother died. Although I do not normally make speeches, I felt I owed it to him - and to my mother - to pay tribute to him at his funeral a couple of days ago. Since then, some people have asked for a copy of what I said, and so I am putting the text here for those who want it. If you don't feel like reading such a long thing, the gist is that I loved my brother enormously and will always miss him. He was a wonderfully generous brother and human being and, by great good fortune, he met a woman called Mary Ellen Field who matched his generosity with an abundance of her own.

"I'd like to start by apologising. This will not be a very good eulogy, when compared to our family's usual standards. The problem is that up until now Mark Colvin has been our eulogiser-in-chief, and he set a very high bar. For both our father and our stepfather, he did the job brilliantly, evoking each of them with a vividness that almost made you believe they were still among us. How nice it would be if I could do the same for him.

For those who don't

know, by the way, I am Mark Colvin's sister. This does mean that, on

the subject of Mark Colvin, I can at least claim to be that much

derided thing, an expert. My mother would be the greatest expert on

him here today - or indeed anywhere on the planet. My cousins, Jamie

and Belinda, who, to our great joy, have flown out from England to be with us to farewell Mark, were both born before me, so

they might be able to argue that they also have the edge. However,

despite missing out on his first four years, as the next sister in

line to him, I reckon I did have quite a lot of experience of Mark

Colvin - although possibly not the Mark Colvin who has been celebrated

in the media since his death.

Yes, I am his sister. And apparently there is a thing called sibling rivalry. Well I wouldn't know. It is said, I admit, that Marko expressed initial disappointment that I wasn't a boy – the story goes that while being read a Christmas story the evening after my birth, (I was born near Christmas) he piped up each time the male pronoun was used, saying, “Him, not her - they laid him in a manger”, “He, not she – he was wrapped in swaddling clothes” etc (I mentioned this to someone in Marko's hospital room the other day and Marko smiled gently, commenting, “Ah, family stories, aren't they always the best')? In any case, if there was any truth to the story, the whole thing took place before I was aware of anything much, and by the time I was noticing stuff, Marko seems to have decided that we were going to be friends forever. We have been ever since.

Our relationship consisted almost exclusively of laughing together, sharing stupid jokes, a love of Molesworth, EL Wisty, Shelley Berman, New Yorker cartoons, deriving amusement from the tormenting of parents and grandparents – in this regard, there was one recurrent idiocy that we shared with our cousins Jamie and Belinda, with whom we spent such a lot of time as children. It involved insisting to our grandmother that the man who took the parking fees in the car park at Winchester - a sensationally unattractive person who always wore a very grubby raincoat and was therefore known to us as “the mackintosh man” - was desperately in love with her; this for some reason was something that totally maddened granny, which of course gave us all great joy.

However, our absolute all time favourite torment routine, something we never really abandoned even in adulthood, was teasing our mother with a rendition of a Fairy Liquid advertisement ubiquitous in our childhoods; “Mummy”, one of us would say, in a sickly voice, “Mummy”, the other would chime in, repeating this tag team repetition, until finally our mother could stand it no more and would reply, reluctantly, often impatiently, presumably having resigned herself to the fact that we were never going to give up. “Yes?” she would say, and after a lot of giggling, we would ask her, “Mummy why are your hands so soft”, breaking immediately afterwards into a saccharine rendition of one of the most saccharine jingles ever penned, which I will spare you.

We also made up routines for long car journeys, dialogues between characters we invented randomly. For some reason, the pair we reverted to most frequently were Nigel and Daphne, a couple of what would now be called Sloanes who loved nothing better than discussing their social calendars. I have no idea why we found this so amusing but it passed the time extremely well. “Nigel, are you going to Lady Northumberland's ball next week?” “Daphne, I'd love to, but I'm going to the Hambledon Hunt Hunt Ball that evening and I simply can't get out of it.”

I realise as I remember these things that one of the worst aspects of losing my brother is not being able to have the opportunity to make him laugh again. How I would love to tell him about Mary Ellen Field having received not one but two letters of condolence following his death - charming, kind, beautifully written letters, both of them from convicted phone hackers serving time in one or other of Her Majesty's jails. He would have laughed and laughed at that, as he would if he'd heard about how one of his closest friends told herself she must pull herself together and get out of the house the day after his death. She had barely gone through the gate when the local real estate agent greeted her, unleashing a downpour of tears, most of which landed on the unsuspecting woman's shoulder. “A real estate agent, of all people,” his friend said afterwards. Yes, Mark would have found the idea of blubbing on a real estate agent wonderfully absurd.

But actually there was more to our relationship than laughter – there was also huge generosity, although I'm ashamed to say it was always from him to me. After a brief hiccup when he was so battered by his experience at prep school that his affection for me was replaced almost exclusively by the response “Stick a beetroot in your cakehole” if I ever attempted to speak to him, I was amazed one morning as we were walking down Victoria Street in London, near Westminster School, the place that restored him after his five horrible years at Summerfields. All of a sudden, Mark vanished, and before I could work out where he'd gone he reappeared, emerging from a sweet-shop doorway. He handed me a small white paper bag containing a quarter of sherbet lemons. He'd decided he'd give me a present, just out of the blue, for no reason, simply because he felt like doing it.

There were many other similar occasions, but another that especially stays with me was an afternoon when he returned to our house at 68 Limerston Street and handed me a brand new book. It was the first ever Paddington Bear novel, when Peggy Fortnum was his illustrator. “I thought this looked as if it might be something you'd like", he told me. It was astonishingly thoughtful and perfectly chosen. I am still grateful for the hours of pleasure he gave me with that unprovoked gesture, as I went on to read and enjoy every one of those early Paddington books.

Marko's generosity continued beyond our childhood - and so did my disgraceful bludging. It is astonishing to remember but there was a time when Sydney had not yet become a place full of hipster cafes, and if you wanted brunch on Saturday you had the choice of a milk bar or fending for yourself. This was the early seventies. I was 17 or 18, working as a motorbike courier, Marko was living in Coogee and I think possibly already at Double Jay or possibly still a cadet. Anyway, on the first morning of each weekend he used to buy a steak and a tin of mushrooms and cook the steak and then add the mushrooms to the pan. By some coincidence, I would usually drop in at around the same time and rather wearily he would share what he had intended to be a meal for one.

Three or four years later, in London, when he was working at the ABC bureau there and I was being paid almost nothing to work for various now defunct magazines, I would sometimes go up to see him at the office they had in Portland Place. He and I and basically everyone else in the rest of the office would head out to a restaurant run by a young Greek Cypriot. Lunch would go on for hours and usually end with complementary Metaxas all round. Much food was eaten, much rubbish was spoken and there was a nice sense of Australian good cheer.

Marko's generosity continued beyond our childhood - and so did my disgraceful bludging. It is astonishing to remember but there was a time when Sydney had not yet become a place full of hipster cafes, and if you wanted brunch on Saturday you had the choice of a milk bar or fending for yourself. This was the early seventies. I was 17 or 18, working as a motorbike courier, Marko was living in Coogee and I think possibly already at Double Jay or possibly still a cadet. Anyway, on the first morning of each weekend he used to buy a steak and a tin of mushrooms and cook the steak and then add the mushrooms to the pan. By some coincidence, I would usually drop in at around the same time and rather wearily he would share what he had intended to be a meal for one.

Three or four years later, in London, when he was working at the ABC bureau there and I was being paid almost nothing to work for various now defunct magazines, I would sometimes go up to see him at the office they had in Portland Place. He and I and basically everyone else in the rest of the office would head out to a restaurant run by a young Greek Cypriot. Lunch would go on for hours and usually end with complementary Metaxas all round. Much food was eaten, much rubbish was spoken and there was a nice sense of Australian good cheer.

On those occasions, as I remember it – and admittedly the Metaxas were not brilliant for one's memory - Mark always shouted me, and always refused to accept repayment. In the same period, I let slip that I needed carpet but couldn't afford it. To my astonishment – when you don't have much money, it is always astounding to learn that anyone else has any to spare - Marko immediately told me not to be ridiculous and gave me 250 quid.

If I wanted to self justify of course I could point out that money was not something my brother cared about. In fact I have rarely met anyone so little interested in material wealth as Mark. If you want proof of how little stuff mattered to him, you only have to look at his arrival to live permanently in Australia. Somehow- and even this I cannot quite credit, but perhaps my stepmother or some other relative did it for him – he managed to organise himself enough to get his belongings, including a rather lovely desk that had belonged to his grandfather, packed up professionally and shipped over to Sydney. After that, however, his attention drifted. Despite nagging from his parents and various other members of the family – or perhaps because of the nagging: after all I do remember my mother having a conversation with him after he'd had a motorbike accident wherein she said, 'Well I hope you will give up riding the motorbike now”, to which he replied, 'Well I was going to until you said that” - he never, ever managed to pick the things up from the wharf; really and truly never; in the end they were seized and used toward payment of the wharf fees he'd accrued. I genuinely don't think he cared at all about that happening.

But it wasn't only with money that Marko was generous; he was equally generous with those more precious commodities, his time and his knowledge. My cousin Belinda often tells the story of how, just before his finals at Oxford, she was bemoaning to him her lack of education. Despite the fact that he had so much else on his mind, Marko still found time to draw up a reading list for Belinda – she has said ever since that what he did for her that day was actually supply her with the education school never had. My daughter Lucy talks about his patience with young people. When you were with him, she says, there was never a sense that he was looking over his shoulder wishing for someone more interesting. Many people at the ABC have told me that he was extremely unusual in his openness, helpfulness, generosity and lack of any guarded competitiveness. I think actually that had he not been a journalist, he would have made a great teacher and certainly he told Mary Ellen Field that one of the things he loved best about her gift of an extra four years of life was the opportunity it gave him to mentor younger colleagues. And, since we are mentioning her, I would just like to highlight her gift and point out that she was the one and only person who matched my brother's generosity with an abundance of her own.

Marko's generosity, his total lack of hesitation about sharing what he had, was something I still admire greatly, not just because I benefited from it. It is a quality encountered very rarely and it was just a small part of a larger element in Marko's character – a trait that never left him and would be unexpected in anyone but particularly in a man of Marko's profession. It was innocence, or at least a kind of innocence - an unshakeable expectation of decency, of fair play, of loyalty in others, a tendency not to suspect low motives. As I say, this quality never completely left him and it was a great part of his charm and loveableness. However, it did make him very vulnerable to hurt.

Perhaps the best illustration of this gentle unworldliness is the story my mother tells about the first children's party she took Marko to. Marko was not a shy child. He went into the party perfectly happily, and before long my mother saw a small girl approach him. They seemed to get on, although the girl, to mum's way of thinking, looked like she was coming on a bit strong. All the same they appeared happy. Mum took her eye off proceedings. The next thing she knew, Marko was hurtling towards her, an expression of complete shock on his face. He looked at mum and then back at the girl, who had remained where he'd left her on the other side of the room.

If I wanted to self justify of course I could point out that money was not something my brother cared about. In fact I have rarely met anyone so little interested in material wealth as Mark. If you want proof of how little stuff mattered to him, you only have to look at his arrival to live permanently in Australia. Somehow- and even this I cannot quite credit, but perhaps my stepmother or some other relative did it for him – he managed to organise himself enough to get his belongings, including a rather lovely desk that had belonged to his grandfather, packed up professionally and shipped over to Sydney. After that, however, his attention drifted. Despite nagging from his parents and various other members of the family – or perhaps because of the nagging: after all I do remember my mother having a conversation with him after he'd had a motorbike accident wherein she said, 'Well I hope you will give up riding the motorbike now”, to which he replied, 'Well I was going to until you said that” - he never, ever managed to pick the things up from the wharf; really and truly never; in the end they were seized and used toward payment of the wharf fees he'd accrued. I genuinely don't think he cared at all about that happening.

But it wasn't only with money that Marko was generous; he was equally generous with those more precious commodities, his time and his knowledge. My cousin Belinda often tells the story of how, just before his finals at Oxford, she was bemoaning to him her lack of education. Despite the fact that he had so much else on his mind, Marko still found time to draw up a reading list for Belinda – she has said ever since that what he did for her that day was actually supply her with the education school never had. My daughter Lucy talks about his patience with young people. When you were with him, she says, there was never a sense that he was looking over his shoulder wishing for someone more interesting. Many people at the ABC have told me that he was extremely unusual in his openness, helpfulness, generosity and lack of any guarded competitiveness. I think actually that had he not been a journalist, he would have made a great teacher and certainly he told Mary Ellen Field that one of the things he loved best about her gift of an extra four years of life was the opportunity it gave him to mentor younger colleagues. And, since we are mentioning her, I would just like to highlight her gift and point out that she was the one and only person who matched my brother's generosity with an abundance of her own.

Marko's generosity, his total lack of hesitation about sharing what he had, was something I still admire greatly, not just because I benefited from it. It is a quality encountered very rarely and it was just a small part of a larger element in Marko's character – a trait that never left him and would be unexpected in anyone but particularly in a man of Marko's profession. It was innocence, or at least a kind of innocence - an unshakeable expectation of decency, of fair play, of loyalty in others, a tendency not to suspect low motives. As I say, this quality never completely left him and it was a great part of his charm and loveableness. However, it did make him very vulnerable to hurt.

Perhaps the best illustration of this gentle unworldliness is the story my mother tells about the first children's party she took Marko to. Marko was not a shy child. He went into the party perfectly happily, and before long my mother saw a small girl approach him. They seemed to get on, although the girl, to mum's way of thinking, looked like she was coming on a bit strong. All the same they appeared happy. Mum took her eye off proceedings. The next thing she knew, Marko was hurtling towards her, an expression of complete shock on his face. He looked at mum and then back at the girl, who had remained where he'd left her on the other side of the room.

“That girl bit me,” he told my mother. He was clearly horrified. Before she could think what she was saying, my mother added to his horror by saying “Well, darling, go and bite her back”.

Needless to say, Mark didn't. He was never aggressive or violent. However, he could be disappointed – and woe betide the person who disappointed him and thought they could still retain his friendship. If Marko put his trust in you or gave you his friendship and you betrayed it, perhaps because he himself was so loyal and such a good friend, he found it well nigh impossible to forgive the hurt he felt as a result. Mind you when that happened, when he did give up on someone, he didn't resort to histrionics. He didn't shout or scream or throw things. In fact, the only sign that he could no longer stand the sight of you was a dawning sense of being locked out from his affection, an intimidating withdrawal of his attention and interest.

Needless to say, Mark didn't. He was never aggressive or violent. However, he could be disappointed – and woe betide the person who disappointed him and thought they could still retain his friendship. If Marko put his trust in you or gave you his friendship and you betrayed it, perhaps because he himself was so loyal and such a good friend, he found it well nigh impossible to forgive the hurt he felt as a result. Mind you when that happened, when he did give up on someone, he didn't resort to histrionics. He didn't shout or scream or throw things. In fact, the only sign that he could no longer stand the sight of you was a dawning sense of being locked out from his affection, an intimidating withdrawal of his attention and interest.

But even then, I was so glad to discover last week, things weren't completely irredeemable, provided you were truly sorry for the hurt you'd caused. After years of wounded silence from Marko, one of our closest relatives apologised unreservedly for something that Marko thought he'd said to him. "I love you" was Marko's immediate reply. Our relative flew over from London and they were together when Marko died.

But enough of this cloying stuff. It is also important to remember that Marko was hugely interesting company. That is why, as well as the laughs and the steak and tinned mushrooms, I will miss so much the endlessly varied conversations we had. During one of our very last, he said to me, “You and I always had so much in common” and that is true. However, once again I was the beneficiary, as Marko's brain was so enormous and so stocked with knowledge, whereas, except on very rare occasions, I was merely the interested looker on. On any topic worth discussing he had such a rich reserve of information and reference stored away inside his head. In the last two or three days of his life alone, despite his being very, very ill, we managed to have some great discussions about among other things Taming of the Shrew and whether it is actually a sexist work - we agreed that it isn't, that it is actually all about love; Les Murray's poetry, most particularly Dog Fox Field; the rich language of observed nature that emerges again and again in Shakespeare's writing, (complete with quotations straight from memory – by Marko, naturally, not me); Memling, Van Eyk and the so-called Northern Primitives and how the only reason we tend to hear more of Michelangelo and da Vinci is that Vasari's writings pushed them to the fore; and Thomas Hardy, who my brother to the very end refused to agree contains traces of humour.

And speaking of humour, I did manage to get one last chuckle out of him. It was very late in the piece, when he was well aware that death was not far away. If I had any doubt about that I would not have mentioned the plans being made to mark his passing. However, he knew and I knew, and so I told him I'd heard that the ABC had a strategy in place for the day of his death that was equal to that devised by the British government in the event of the death of the Queen Mother. He looked - unsurprisingly, given his utter modesty about his own significance - astonished and also gratified, in a I-must-stifle-any-tiny-scrap-of-incipient-vanity kind of way. To help in this regard, I told him that I was going to nip out immediately and look for a suitably flowery hat for him to wear from now on. He laughed, relieved that he had been rescued from the dangers of a plunge into full blown self-importance.

That was so typical. My brother was never a seeker of limelight, never a big noter. When filming, he abhorred noddies and appeared as little as humanly possible in the footage he shot. He must have known at some level that he was much loved by many, but it never made him self-important. While, like anyone he would have been gratified by the tributes that have been paid to him since his death, he would have been amazed as well. I doubt that he would have thought he deserved them.

Speaking of tributes, I was looking through Mark's papers the other day and found something he'd written for the family of Bahram William Dehqani-Tafti, his interpreter in Iran. Bahram was assassinated on 6 May, 1980. His death horrified Marko. His tribute to Bahram reads as follows:

"You get to know people faster in a war zone: during the three days he spent with us in Kurdistan, Bahram revealed many of his qualities: he was courageous, extremely level-headed, and at the same time sensitive to the people surrounding him. He had an enquiring mind without being inquisitive; but one of the things which struck me most forcibly was his ability to look at a problem from all directions.”

Mum felt that those words could just as well have been written about Marko himself.

In the instant after my brother died. out of nowhere a memory from our childhood leapt into my head. It was from the very early 1960s, we were in Victoria, in a car driving along a remote and empty road. Marko and I were in the back, playing up as usual. Eventually my parents ran out of patience. They stopped the car. "If you don't behave" they told us, "we will put you out on the side of the road and leave you".

But enough of this cloying stuff. It is also important to remember that Marko was hugely interesting company. That is why, as well as the laughs and the steak and tinned mushrooms, I will miss so much the endlessly varied conversations we had. During one of our very last, he said to me, “You and I always had so much in common” and that is true. However, once again I was the beneficiary, as Marko's brain was so enormous and so stocked with knowledge, whereas, except on very rare occasions, I was merely the interested looker on. On any topic worth discussing he had such a rich reserve of information and reference stored away inside his head. In the last two or three days of his life alone, despite his being very, very ill, we managed to have some great discussions about among other things Taming of the Shrew and whether it is actually a sexist work - we agreed that it isn't, that it is actually all about love; Les Murray's poetry, most particularly Dog Fox Field; the rich language of observed nature that emerges again and again in Shakespeare's writing, (complete with quotations straight from memory – by Marko, naturally, not me); Memling, Van Eyk and the so-called Northern Primitives and how the only reason we tend to hear more of Michelangelo and da Vinci is that Vasari's writings pushed them to the fore; and Thomas Hardy, who my brother to the very end refused to agree contains traces of humour.

And speaking of humour, I did manage to get one last chuckle out of him. It was very late in the piece, when he was well aware that death was not far away. If I had any doubt about that I would not have mentioned the plans being made to mark his passing. However, he knew and I knew, and so I told him I'd heard that the ABC had a strategy in place for the day of his death that was equal to that devised by the British government in the event of the death of the Queen Mother. He looked - unsurprisingly, given his utter modesty about his own significance - astonished and also gratified, in a I-must-stifle-any-tiny-scrap-of-incipient-vanity kind of way. To help in this regard, I told him that I was going to nip out immediately and look for a suitably flowery hat for him to wear from now on. He laughed, relieved that he had been rescued from the dangers of a plunge into full blown self-importance.

That was so typical. My brother was never a seeker of limelight, never a big noter. When filming, he abhorred noddies and appeared as little as humanly possible in the footage he shot. He must have known at some level that he was much loved by many, but it never made him self-important. While, like anyone he would have been gratified by the tributes that have been paid to him since his death, he would have been amazed as well. I doubt that he would have thought he deserved them.

Speaking of tributes, I was looking through Mark's papers the other day and found something he'd written for the family of Bahram William Dehqani-Tafti, his interpreter in Iran. Bahram was assassinated on 6 May, 1980. His death horrified Marko. His tribute to Bahram reads as follows:

"You get to know people faster in a war zone: during the three days he spent with us in Kurdistan, Bahram revealed many of his qualities: he was courageous, extremely level-headed, and at the same time sensitive to the people surrounding him. He had an enquiring mind without being inquisitive; but one of the things which struck me most forcibly was his ability to look at a problem from all directions.”

Mum felt that those words could just as well have been written about Marko himself.

In the instant after my brother died. out of nowhere a memory from our childhood leapt into my head. It was from the very early 1960s, we were in Victoria, in a car driving along a remote and empty road. Marko and I were in the back, playing up as usual. Eventually my parents ran out of patience. They stopped the car. "If you don't behave" they told us, "we will put you out on the side of the road and leave you".

My brother immediately grabbed the door handle, opened the door and leapt out. He began walking. I didn't see my parents' faces because I was so shocked myself. What would happen to him? Would we ever see him again? He was striding away ahead of us. He had called our parents' bluff.

My father started the car again and drove after Marko. Then ensued a ridiculous reversal of roles whereby my parents were reduced to creeping along in first gear beside their son's walking figure, begging him to get back into the car.

It was an odd thing to think of at that moment but I like to believe it was a metaphor. Marko has leapt out of the car we're all travelling in, he has shown us that what we think we are afraid of is not actually anything to be frightened of. He is striding off down the road."

My father started the car again and drove after Marko. Then ensued a ridiculous reversal of roles whereby my parents were reduced to creeping along in first gear beside their son's walking figure, begging him to get back into the car.

It was an odd thing to think of at that moment but I like to believe it was a metaphor. Marko has leapt out of the car we're all travelling in, he has shown us that what we think we are afraid of is not actually anything to be frightened of. He is striding off down the road."

Please accept my condolences.

ReplyDeleteThank you, dear George. I should have said, for those unfamiliar with him, that if you want to know more of my brother's story or to see some of his work as a journalist, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation website should be able to guide you to it.

Deletesuch beautiful words, thank you.

ReplyDeleteHe was so terrific and I loved him very much. Still do.

Delete